Standard & Poor’s Financial Services, the ratings agency, has downgraded China. The ratings agency bumped the country down from AA- to A+, citing increased debt and financial risks. The move comes only weeks before the Communist Party shuffles key leadership posts and sets policy priorities at its twice-a-decade congress.

China’s growth has been credit-led and credit-dependent over the last several years, but as history shows, financial mismanagement ’s consequences materialise only with time.

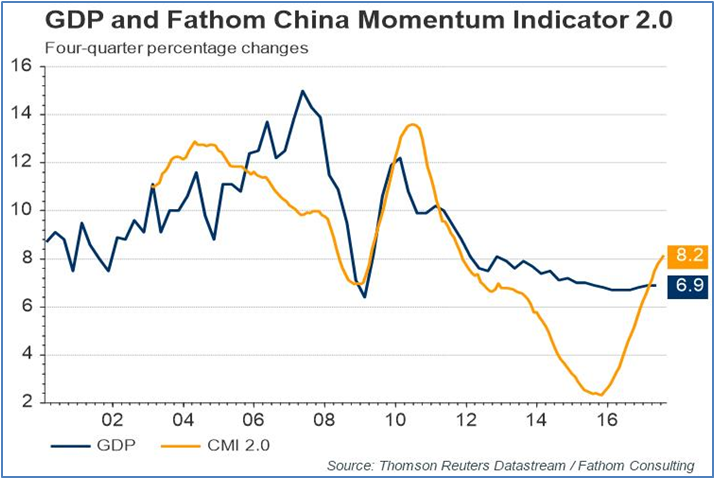

Fathom Consulting, an independent, UK-based research outfit, which has developed its own proprietary China Momentum Indicator (CMI), publishes a chart that tracks the country’s GDP growth rate, implied by its CMI, and the official, real GDP growth rate. Its growth estimate, published last week, shows the Chinese economy growing at 8.2% versus the official estimate of 6.9 per cent.

The last few years, though, showed different results: the CMI trailed the official growth estimate significantly, indicating that China’s official statements were overstating the real growth rate. So, what changed? This is what the report says:

“CMI 2.0 stood at 8.2% in July, 0.2 percentage points higher than June’s revised reading. This marks a significant rebound from the trough of 2.3% in October 2015, a consequence of China’s policymakers resorting to what they know best and re-administering the growth medicine of 2008–2009.

Those hoping that this pickup in economic activity will be sustainable are likely to be disappointed. Of the ten sub-components included within our CMI, those associated with China’s old model of investment-led growth are primarily responsible for the rebound: all three freight indicators, especially railway freight, as well as real imports and the commodity price index.

While policymakers’ current tactics may boost China’s economic growth in the short term, the inefficiency with which credit is being distributed, alongside limited evidence of rebalancing, is harming China’s long-run growth prospects.”

How long can this go on? An article by James Kynge in December 2016[1] refers to how the Song dynasty mismanaged the economy. They printed money; eventually, inflation was upon them, and by the time the Mongols arrived, the empire was weak politically, economically and militarily. Considering it took 70 years for the Song dynasty’s disastrous economic policies to become apparent, these are still early days for the economic policies of today’s China to unravel. In other words, Beijing has time to continue to mismanage the economy.

When did China’s disastrous economic policies start in earnest? If from the new millennium, then they have another half a century to go.

Dating China’s top-down and command-driven policies is problematic. If pinning the beginning to the early 1990s after the Tiananmen Square protest, then Yasheng Huang at MIT (in his book, Capitalism with Chinese Characteristics) calls the period between 1979 and 1992 the golden era of reforms. There was genuine devolution; local autonomy and enterprise were encouraged. Centralisation began only after 1992 when the “Shanghai Clique”, also the title of Yasheng Huang’s book, gained power. Then came the Asian crisis, entry into the World Trade Organisation in 2001 and an investment- and export-driven growth model from 2002 onward.

The 2008 crisis presented a dilemma for China: its export market–the western world and the United States, in particular–was poised to collapse. But Beijing also believed that its time had arrived. That is why, in 2009, it began floating discussion papers for a multi-polar world, suggesting the use of multiple reserve currencies, not only U.S. dollar-based, besides other changes.

But the fact that China had to unleash a massive economic stimulus for a crisis that was supposedly a North Atlantic one underscores its vulnerability, which persists to this day. In August 2017, Moody’s released a report[2] on the credit intensity of China’s growth, and this sentence, unfortunately, is true:

“Although the contribution of domestic consumption to GDP growth has gradually been increasing, a core of China’s growth model remains investment funded by credit.”

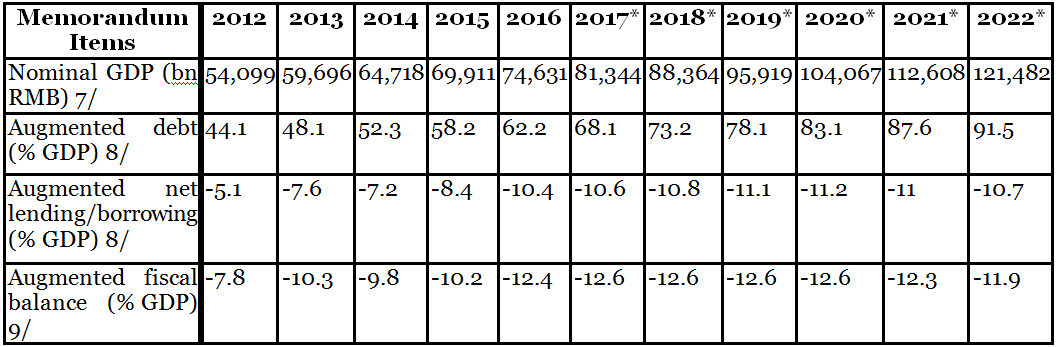

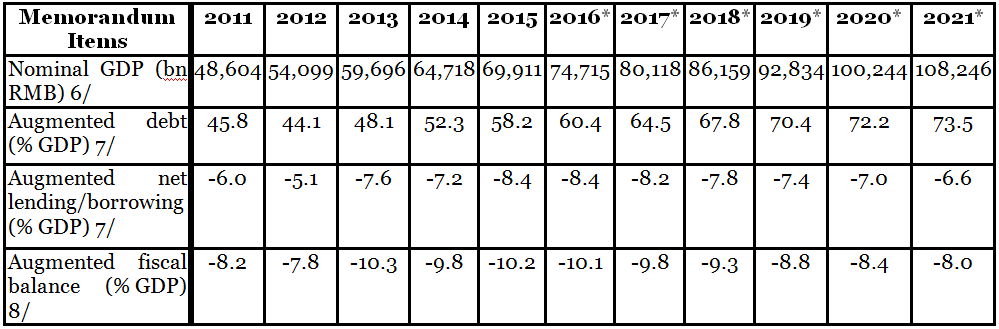

That is as mild a rebuke as it can get. The reality is far worse. The credit intensity of growth continues to rise. Not even the second derivative has turned negative. According to the Bureau of Indian Standards’ statistics, the overall non-financial debt/GDP ratio was 257.0% by the end of last year. It was as low as 144.9% in December 2007. Other authoritative research reinforces this conclusion. Charlene Chu of Autonomous Research, who was earlier the China credit analyst at FitchRatings, thinks that China’s non-performing assets could be as high as 25% of bank advances.[3] The IMF in its Article IV report for 2017 pointed out that China would do it’s all to achieve its 2020 growth target and that its ‘augmented’ fiscal deficit ratio was expected to be 12.6% of GDP in 2017.

That China’s underlying fiscal health has deteriorated quite rapidly in the last one year can be seen from the same figures that the IMF projected in last year’s report below. For example, the fiscal deficit for 2017 was projected at 9.8% of GDP.

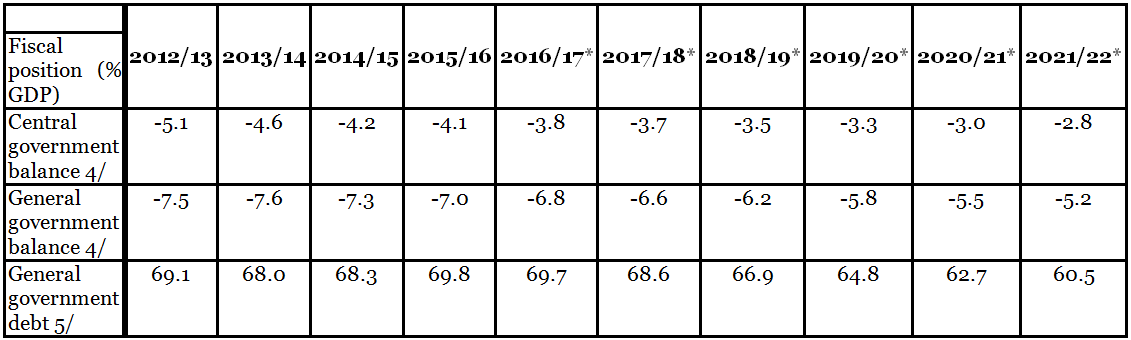

Fiscal deficit minus expected revenue from land sales equals net lending/borrowing in the above tables. In other words, properly accounted fiscal balance and public debt are worse than India’s general government (centre + states) fiscal balance and public debt. The table below provides corresponding figures for India on general government deficit and debt to facilitate comparison.

Despite the recent downgrade in May this year, China has an A1 credit rating from Moody’s.

The fiscal health parameters and the overall level of debt convey the message that China’s economy and its exorbitantly high debt levels pose a huge risk for China’s social, political and economic stability– especially in the context of the Communist Party’s legitimacy being derived from economic growth and its determination to pursue it ahead of other considerations.

This risk is accentuated by the fact that on top of the one-party rule, there is one-person rule in China now. That increases the dangers of groupthink quite significantly. Recent economic stability, including currency stability, has much to do with the upcoming National People’s Congress in October. It has come in the wake of draconian controls on capital outflows and a massive about-turn on foreign acquisitions by Chinese corporations[4].

On the face of it, China’s currency is not expensive. After all, the country runs a current account surplus, its foreign exchange reserves are ample and its economic growth rate is above 6%. China’s stock markets are one of the strong performers in the world this year.

But, on risk considerations, the currency is expensive. The risk of future inflation that lurks in the massive debt accumulation is missing in the currency’s valuation.

Stephen Roach, formerly with Morgan Stanley, has been a long-standing China-watcher and, importantly, he is a Sinophile. Commenting on China’s Belt and Road initiative (BRI), he commented in his syndicated global column in May that it carried three implications. One, it signalled that China had practically conceded that economic rebalancing towards more domestic consumption was much more difficult than thought. Two, the BRI global push was old economy as it relied on excess capacity in state-owned enterprises. Three, this project reflected a recasting of governance. It not only reflected the increasing concentration of power in the hands of the President, but also a more outwardly focused, more assertive and more power-centric China.[5]

In short, time is running out for China’s ambitious policy-makers. Over the next two or three years, a fairly severe economic crisis appears more likely than not.

Dr. V. Anantha-Nageswaran is Adjunct Senior Fellow, Geoeconomics Studies, at Gateway House.

You can read exclusive content from Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations, here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2017 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited

References

[1] James Kynge, ‘China’s liquidity flood stirs memories of the Mongols and Mao’, Financial Times, 2nd December 2016, <https://www.ft.com/content/7d31805c-b7ca-11e6-961e-a1acd97f622d>

[2] ‘Reduced Credit Intensity of Growth Key to Achieving Policy Objectives’, Moody’s Investors Service, 14th August 2017

[3] Charlene Chu: ‘Prominent China debt bear warns of $6.8tn in hidden losses’, Financial Times, 17th August 2017, <https://www.ft.com/content/3bc4da08-8171-11e7-a4ce-15b2513cb3ff>

[4] See ‘Beijing Investigates Loans to China’s Top Overseas Deal Makers’, Wall Street Journal, 22nd June 2017, <https://www.wsj.com/articles/beijing-is-investigating-some-of-chinas-top-overseas-deal-makers-1498117170>

[5] Stephen Roach, ‘Rethinking the next China’, Project Syndicate, May 2017, <https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/global-china-risks-and-opportunities-by-stephen-s–roach-2017-05>