This article is the first in a two-part series. Read the second part here.

The flourishing multi-faceted India-France relationship is best represented by the booming commerce between the two countries. There are over 1,000 French companies in India, with 40% located in the Mumbai-Pune region alone, generating 300,000 jobs. Over the years, France has invested $9.97 billion in India[1], making it the 11th largest investor in the country.[2]

The resumption of long-stalled negotiations for a Free Trade Agreement with the European Union, of which France is the current president, will give a strong boost to the $8.23 billion[3] in bilateral trade.

Although these robust business ties are the result of intense diplomatic and business engagement over the last two decades, their strength derives from three hundred years of familiarity[4] due to the French colonial presence on the Indian subcontinent.

Bombay’s colonial history intersected with that of the French in India in 1668 when the island city competed with the French East India Company’s first outpost at Surat on India’s west coast for business and strategic alliances. The city was a pawn in the bitter Anglo-French rivalries on the subcontinent, which reached their zenith in the Anglo-Mysore wars. Finally, the city became an important stopover for all French shipping from the mid-19th century.

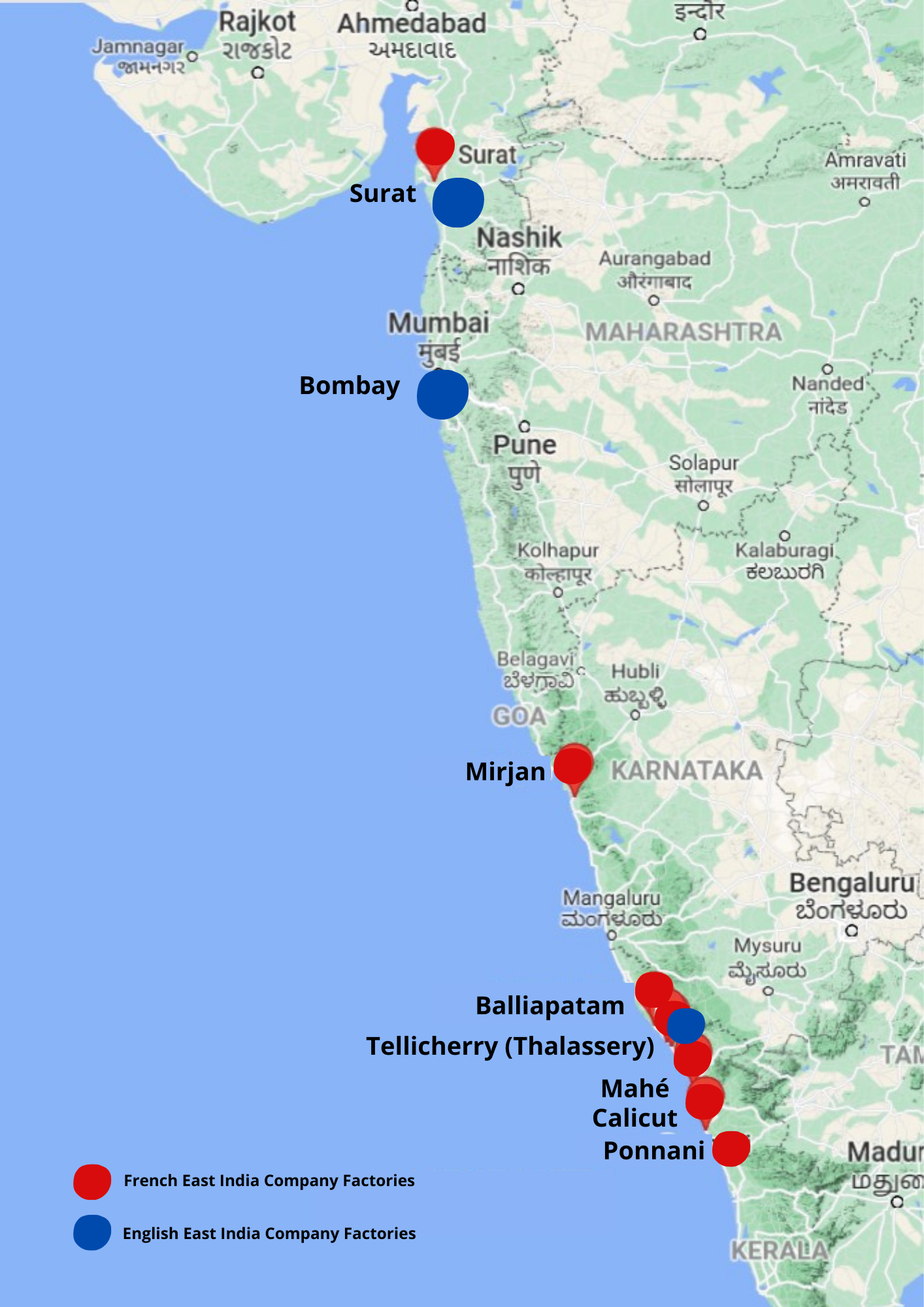

French and English trading outposts in the 18th century.

Bombay’s merchants began doing business with the French in earnest in the second half of the 17th century, first in the Mughal port of Surat. There, it was led largely by a local shipping agent and dubash (interpreter), Nasarvanji Kavasji, the founder of the famous Bombay Petit family.[5] Descendants of this family carried on the tradition of handling French trade in raw cotton, piece goods, indigo, and French imports like lead, copper, and tin, long after they relocated from Surat.

The ships of the Compagnie des Indes Orientales[6] or the French East India Company, dropped anchor at Swally downriver from the Mughal port of Surat on the River Tapi in 1666.[7][8]The first French factory was established on Indian soil two years later. [9] France was a latecomer into the Indian Ocean trading world. It was the largest buyer of Indian cotton and silk textiles and spices, especially Malabar pepper, used by the French as a preservative and marinade for meats. These much-valued condiments and textiles were bought at inflated prices from Amsterdam or from smugglers. It was necessary to compete with the Dutch and the British in the Eastern Hemisphere. After an early, unsuccessful attempt to enter the India trade, Louis XIV’s finance minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert, stressed the creation of a French East India Company as a project of national importance.

The new French East India Company, established in 1664, sailed their ships shortly after into the Indian Ocean. It soon clashed with the English East India Company (EEIC) in the seas off Bombay, located on the subcontinent’s west coast where both had multiple trading outposts and both traversed the same shipping route between Surat and the Malabar Coast. The companies competed fiercely to buy Indian goods while also selling what they had imported from the West in the subcontinent’s markets, and their rivalry deteriorated into military threats and conflicts whenever Britain and France fought overseas.

The French proved keen competitors by acquiring firmans – permits – from the Sultan of Bijapur in 1668 to trade from Rajapur, and in the same year for Raibaug from the Maratha King Shivaji, who was wary of the English.[10] To further consolidate their market access, the French supplied European arms and ammunitions to Shivaji, at a time when the Mughals and other Indian armies were using outdated Turkish equipment, thereby making the Marathas an even greater threat to the EEIC in Bombay.

The death of Mughal emperor Aurangzeb in 1707 resulted in the breakdown of a strong centralised Mughal administration across India, particularly in the Deccan and Bengal, which were geographically distant from its capital, Delhi. In the vacuum of power, regional Mughal governors like the Nizam of Hyderabad and Nawab of Arcot in the Deccan asserted themselves as rulers, whilst the power of the Maratha confederacy in Bombay’s immediate neighbourhood increased exponentially and threatened the city. It was in the interstices of the power struggle between regional kingdoms that the Europeans found opportunities to take sides in exchange for trading privileges and revenue yielding territory.[11] Their military and naval might proved strong bargaining chips in Anglo-French alliances with local rulers. The two companies were invariably pitted against each other, although merchants from the English and French companies interacted and even socialised with one another during peacetime.[12]

Bombay was caught in the crosshairs of the Anglo-French conflict when Mysore’s ruler Haider Ali, who had French military advisors and officers, invaded the Malabar in 1766 and blocked all English trade in pepper, sandalwood, cinnamon, and teak.

Admiral Suffren meeting Haider Ali in 1782.

This blockade, the first of many, impacted Bombay’s China trade as Malabar goods were much valued in Chinese markets. Their export also reduced the quantity of silver specie being shipped to Canton to pay for Chinese tea.[13] Bombay’s inability to source these commodities further increased its financial dependence on Calcutta – it was a loss-making presidency with no hinterland. Correspondence, from 1788 to 1790, between Governor-General Warren Hastings and the EEIC board in London indicated that the city faced the ignominy of being downgraded to a trading outpost from presidency.[14] Luckily, this was not destined to happen!

Determined to evict the English with French help after the Second Mysore War of 1780-84, Tipu Sultan, son of Haider Ali, sent emissaries in 1787 to France to forge a military alliance. The overseas outreach did not fructify. Instead, when news of the Mysore mission to France reached the English, it aggravated them further. A 1789 attack on English ally, the King of Travancore, led to Tipu’s decisive defeat in the Third Anglo-Mysore War (1789-1792) at the hands of the Marathas and the Nizam of Hyderabad and their English ally.[15]

The Bombay Army’s Sixth Battalion’s engagement in the Second Mysore War is memorialised in the Gate of Mercy Synagogue (Mumbai) built in 1796 by native commandant Samuel Ezekiel Divekar whose life along with those of his men was spared by Tipu Sultan.

Bombay’s tryst with France[16] however, did not end with the Anglo-Mysore wars and its merchants never lost touch with their French counterparts. The Compagnie des Indes Orientales, whose finances were always in a parlous state, was reconstituted into a financially stronger Compagnie Perpetuelle des Indes in 1723. Though the latter was liquidated shortly after the French Revolution of 1789, the company’s dissolution resulted in numerous Frenchmen – traders, officers and soldiers, sailors and captains – all seeking their fortune and work in the employ of Indian rulers. Many operated from the subcontinent’s remaining French enclaves of Mahe, Yanam, Karaikal, Pondicherry, and Chandernagore.

A lucrative phase in Bombay-France economic relations opened in 1860 when the Franco-English Treaty of Free Exchange was signed. It made Bombay a key port for the French on India’s west coast, insuring lively trade between the two.

Sifra Lentin is Fellow, Bombay History, Gateway House.

This article is the first in a two-part series. Read the second part here.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2022 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References:

[1]The highest French FDI equity inflows are in the services sector (18.94%), with cement & gypsum products (9.86%) in the second place, followed by air transport (including air freight) (7.98%), petroleum & natural gas (7.55%) and miscellaneous industries (7.38). Most big French groups have their subsidiaries in India. There are also a few joint ventures and liaison offices of French companies in India. 39 of the 40 CAC 40 (French Stock Market Index) companies are present in India. Around 50-70 SMEs are also present in India essentially in the mechanical and pharma-chemical sectors.

Development, defence (French Scorpene submarines are built at Mazagaon Docks Limited in Mumbai), critical infrastructure, climate change technology (solar energy), are other important sectors which receive French FDI, technology sharing and collaborations.

[2] France is the 11th largest foreign investor in India with a cumulative investment of USD 9.97 billion from April 2000 to September 2021 which represents 1.78% of the total FDI inflows into India according to statistics provided by the DIPP. See https://www.eoiparis.gov.in/page/india-france-economic-and-commercial-relations-brief/: (Accessed on 14 February 2022)

[3] This is for the year 2021-22.

[4] See: https://www.gatewayhouse.in/more-than-a-whiff-of-france-in-bombay/

[5] Nasarvanji Kavasji immigrated to Bombay in 1785, which indicates he was the agent for all French shipping at Surat in the latter half of the 18th century. Edwardes, S.M., Memoir of Sir Dinshaw Manockjee Petit, First Baronet, 1823-1901, (England, Frederick Hall at The Oxford University Press, 1923), p. 3.

[6] The Compagnie des Indes Orientales founded by imperial France’s finance minister, Colbert, in 1664, in order to source Indian goods particularly cotton and silk cloth, spices and indigo at reasonable prices, did not get an enthusiastic response from French merchants. This resulted in Louise XIV subscribing to a large part of the capital of the company. This made it an imperial venture rather than a business one. The bureaucratic interference in the French East India Company was a major factor in its unprofitability. When the Company was reconstituted in 1723 as Compagnie Perpetuelle des Indes by a merger with the French Occidental Company, it marked the beginning of a period of profitability.

[7]The Firman (in this context a written royal order or permission) granted to the French by Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb is dated 11 August 1666. This granted the French permission to set up a factory at Swally and to trade at Surat on the same terms enjoyed by the English and the Dutch companies.

[8] In 1665 the English Expedition finally succeeded in wresting possession of Bombay, which had been gifted in dowry to the English monarch Charles II on his marriage to the Portuguese princess Infanta Catherine da Braganza in 1661. Portuguese landholders on the islands resisted the handing over of the Bombay archipelago of seven islands to the English Crown.

[9] Attempts were made in 1604, 1615 and 1642 by French monarchs to establish companies to trade in the East.

[10] Additional French trading outposts on the west coast were at Mirjan, Balliapatam, Tellicherry, Ponnani, Calicut and Mahe. The English also had factories at some of these places like at Tellicherry.

[11] Anglo-French military and political rivalries in North America, Europe, North and West Africa and in the Indian Ocean, combined with their keen competition on the Subcontinent to source Indian goods in a timely manner and at a reasonable price, resulted in them being rivals in landmark battles like the Battle of Plassey, the Battle of Buxar, and the Anglo-Mysore Wars, which led to vast territorial acquisitions for the EEIC and later the British Raj.

[12] Vincent Rose, Zenith in Pondicherry, chapter from Vincent, Rose (ed), The French in India: From Diamond Traders to Sanskrit Scholars (New Delhi, Popular Prakashan Pvt. Ltd.,1990), p.53.

[13] This was in the early years of Bombay’s trade with Canton. Later the EEIC shipped opium in large quantities to China from Bombay and Calcutta ports, to correct this trade imbalance in their favour.

[14] Nightingale, Pamela, Trade And Empire In Western India 1784-1806 (UK, Cambridge University Press, Reprint 2008), pp. 46-50.

[15] Punitive conditions were imposed on Tipu Sultan by the victors. In addition to the partition of Mysore’s territory, he had to pay war reparations of Rs 30,000,000 and hand over two of his sons to the English.

[16] In 1860, the French had five colonies in India, namely Mahe, Pondicherry, Karaikal, Yanam and Chandernagaore, which it gave up under the Treaty of Delhi (1954). France’s attention in the Indian Ocean region was now on French Indo-China (former Cambodia-Laos-Vietnam), and of course, its early acquisitions of Mauritius (Ile de France) and Reunion Island.