Asia’s Strategic Corridors to India

CLICK HERE TO VIEW THE DIGITAL VERSION OF THE MAP

Thousands of years ago, Indian and Chinese scholars, Arab merchants, Christian missionaries and Persian poets travelled freely through the vibrant, flourishing region which we now know as Asia. At its centre was India, the source and recipient of the culture, knowledge and trade that flowed seamlessly from east to west and north to south.

Then European colonisers came to Asia and drew boundaries that tore apart this capacious fabric. In India, the British developed corridors to favour their own trading and military interests. For instance, the Stillwell Road that starts in Assam in India and connects to Myanmar, was originally developed by the Allies during World War II to provide supplies to the Chinese fighting the Japanese.

Now, over six decades after the end of colonisation, Asia is resurgent. Japan, India, China, South Korea and the ASEAN countries are once again emerging as the growth centres of the world. New connections are being created and old ones redrawn by Asian nations to meet their own strategic needs.

India too must be a part of the build-out of these grand linkages, as political borders blur and give way to the reintegration of Asia.

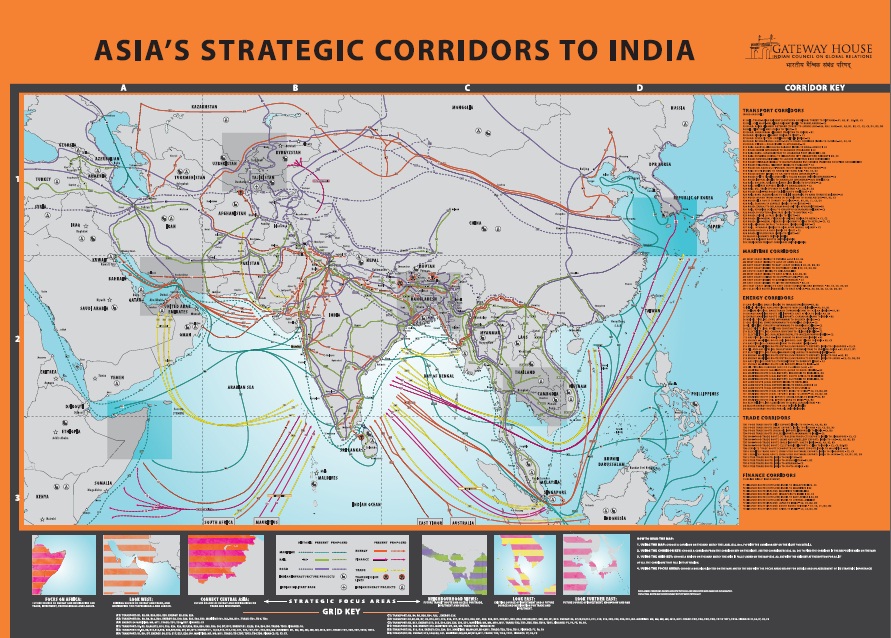

To assess the necessity, possibility and potential of the corridors, Gateway House has done an ambitious study of India’s strategic links – road, rail, maritime, energy, finance and trade – with other parts of Asia.

The importance of a corridor stems from a composite of multiple factors. It could either fulfil a critical need for India (for example, energy from Saudi Arabia or investment from Japan), or provide access to a country (to Afghanistan, for example, through Chabahar port in Iran), or strengthen links with our neighbours (for example, Indian investment in the Sittwe port in Myanmar).

The map that has emerged as a result of our study reveals India’s extensive linkages in Asia. It highlights the progress India has made in forging multiple links with six strategic regions – Central Asia, West Asia and East Africa to our west, South-East Asia and East Asia to our east, and our immediate neighbourhood.

To the east, our official Look East policy, launched in the early 1990s, has been partially successful. The hilly terrain and volatile security situation in our north-eastern region has impeded attempts to revive the physical connectivity with South East Asia through Myanmar. On the other hand, maritime and virtual corridors that carry trade and investment have flourished. Singapore, Indonesia and Malaysia have become important trade destinations for us via maritime routes. Singapore is a source of trade and capital, and thus connected to India by both maritime and virtual corridors. The potential is huge: the research done by Gateway House shows that up to 50% of our imports from China can be sourced instead from ASEAN countries, putting to good use the India-ASEAN free trade agreement.

Looking Further East, Japan and South Korea have emerged as important sources of investment and know-how for India. The joint venture with Japan to build the Delhi Mass Rapid Transport System and the Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor illustrates how capital from Japan is helping us finance critical domestic infrastructure projects. South Korean chemical and electronics companies, and Chinese information technology companies, have made similar investments.

We are not yet looking north, even though an official Connect Central Asia policy was announced in 2012. Regrettably, it is the only region where all countries have lost ground to China. We had good relations in the region when Central Asia was part of the former Soviet Union, but the linkages date back further, to the 15th century. That’s when Babur, born in Ferghana in present-day Uzbekistan, conquered Samarkand, crossed the Hindu Kush into Afghanistan, captured Herat, and entered India to establish the Mughal empire from Delhi. But even today the 1947 partition of India by the British denies us direct access to the region and its energy resources.

One way to re-create the old northern silk routes into Central Asia is to team up with Russia – which has also ceded influence to China. India has a large pool of skilled and unskilled labour, and expertise in financing and leasing services, while Russia has expertise in engineering, heavy machinery, and regional politics. All these are skills needed in Central Asia. Without a joint effort, both India and Russia risk losing this vital connection.

The corridors to West Asia demonstrate the success of our official Look West policy, launched in 2005. We have maintained strong, diverse links with Iraq, Iran, Saudi Arabia and Qatar to secure our energy needs, to sustain trade and cultural exchanges, and to protect the 6 million Indian expatriates who are a productive part of the workforce there and who remit $40 billion annually to their families in India. So far, our neutrality towards the warring factions in the region and non-interference in the Arab uprisings has served us well.

As oil dries up in West Asia and the stability of the region deteriorates, East Africa is becoming an important substitute for our energy needs. Uganda, Kenya, Somalia, Ethiopia, Tanzania and Mozambique are emerging as new sources of oil and gas. India’s official Focus Africa policy, launched in 2002, has helped set the stage. Indian private companies already have oil and gas investments in Kenya and Tanzania respectively, while our public enterprises are involved in building critical rail infrastructure. These countries are also becoming a key destination for investments and professionals from our software, telecom, and financial sectors.

In India’s Neighbourhood, integration is stymied by politics. Intra-SAARC trade amounts to a dismal 5% of the grouping’s total trade with the world. This is low compared to the intra-ASEAN trade of 26% and to the whopping intra-EU trade of 65%. The vulnerability is most apparent in the region that includes the narrow 20-kilometre stretch called the ‘Chickens Neck’, which connects our north-eastern states with the rest of India, and borders Nepal, Bhutan and Bangladesh. A transit, trade and energy corridor through Bangladesh and access to South-East Asia through Myanmar remains an unrealised two-decade-old aspiration.

Within India, the region between Delhi and Mumbai remains the most important economic corridor. It connects our two most important economic centres, has the densest concentration of gas and oil pipelines, and the most advanced physical connectivity bolstered by the construction of the Dedicated Freight Corridor.

Overall, it is not surprising that China is leading the way in building transnational corridors. It has been swift and focused in its search for resources, largely powered by strategic planning, state funding and engineering excellence. The construction of the parallel oil, gas and rail lines from Kunming province to Myanmar is a case in point.

India is less focused in its approach. Our initiatives are poorly designed and under-funded. Added to that is the volatile security situation in Afghanistan and Pakistan, the previously non-cooperative governments in Bangladesh, and geographical barriers within the terrain bordering China and Myanmar, all of which have constrained our outward expansion.

Despite the physical and political barriers, we are now reaching beyond South Asia, bypassing our immediate neighbours. The construction of Chabahar port in Iran will give us access to Afghanistan and Central Asia, and the construction of the Sittwe port in Myanmar will bind us more closely to ASEAN. More recently, we have done well in capitalising on the virtual links that carry investments and know-how.

Remarkably, as the map shows, India’s private and public sector companies are already building infrastructure and investing in energy companies around Asia.

If we can link better with the six regions highlighted in the map, we can further cement the relationships necessary to fuel India’s economic growth. If the grand corridor can be completed, we can once again become the hub of economic activity as we once were when the Grand Trunk Road connected Chittagong to Kabul, the Silk Route connected Turkey to India, and the Spice Route connected South-East Asia to East Africa.

Our vision of reuniting with the rest of Asia by building corridors is a formidable but feasible challenge.

The ‘Asia’s Strategic Corridors to India’ map is available only to Gateway House members. If you are interested in becoming a member, click here for more details.

This map was exclusively created by Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2014 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.