The recently concluded 8th BRICS summit in Goa (October 15-16) marked the beginning of operations by the BRICS’ New Development Bank (NDB), headquartered in Shanghai. The implementation of its Contingency Reserve Arrangement also came into force, the event seeking to further trade and financial integration between its member countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa). [1]

An immediate outcome of the Summit was the signing of the ‘BRICS Inter-Bank Co-operation Mechanism’ two days later (18 October) in Shanghai, between NDB and a representative bank from each country, which will facilitate, among other practices, interest and currency swaps between member states. [2]

All these calibrated steps by BRICS are aimed at establishing a multilateral geo-economic global order, and importantly, for emerging economies to be able to avail of alternatives to the International Monetary Fund and World Bank, the twins conceived in 1944. What is interesting is the fact that the Chinese port city of Shanghai has emerged as an axis for financial linkages between the five-member nations, with the NDB headquartered there.

Historically, Shanghai emerged as a financial centre much after the British colonial port city of Bombay did, but much like it, its early colonial history, built heritage and fortunes too were the result of pioneering Indian, English, European, and American traders with China. Its early founding years as a colonial port city [3] were greatly impacted by Bombay and its merchant community.

The First Opium War (1839-1842)

The entry of Bombay’s cotton exports in the English East India Company’s trade with China was crucial in the larger scheme of the 18th century’s global trading world as it provided a tradable commodity other than silver bullion and specie (money in the form of coins rather than notes), which the Company used to purchase its annual tea imports.

An indication of this drain of silver from England to China during this period comes from the manifest of four English ships that went to China in 1751; they carried £119,000 worth of silver as against just £10,842 in goods. [4] This ratio – 11:1 –, persisted till the late 18th century: Shanghai was not open to foreign trade at this time.

The introduction of Indian opium – a banned substance in China – turned the balance of trade at Canton in favour of England by the turn of the 19th century. Within a period of three years only (1806-9), approximately Spanish silver $7 million was shipped in the opposite direction from China to India.

Bombay played a primary role in this trade, 1830 onwards, as Malwa opium, shipped from Bombay, was not only cheaper, but more profitable than its Bengal variant. So when Chinese Commissioner Lin Zexu finally cracked down on this illicit trade at Canton in March 1839, of the 20,000 chests confiscated and destroyed as many as 7,000 belonged to Bombay merchants [5]

This destruction of the contraband triggered the First Opium War (1839-1842) – the first war between the Chinese empire and the West. Prior to this, foreign merchants were confined to their walled enclave for 47 days, which too caused aggravation. But the increasing outflow of silver from China, combined with the rapidly expanding market for opium among its people, alarmed the imperial Chinese court.

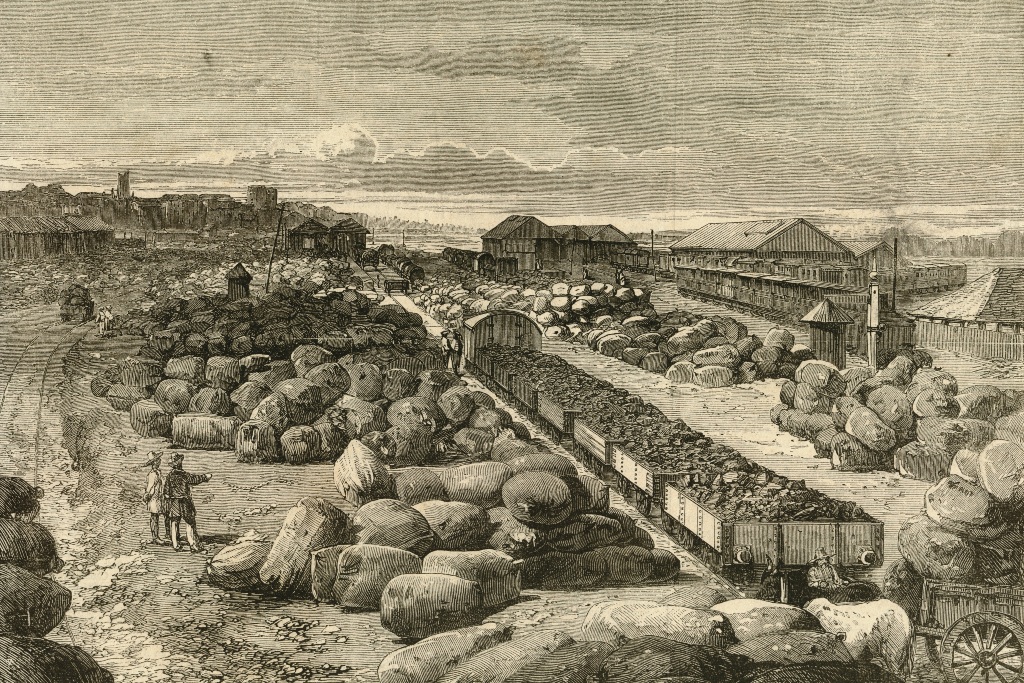

Sailing into Shanghai

Shanghai became a treaty port; open to foreign trade, under the Treaty of Nanjing (1842). This treaty, which marked the end of the war, also saw five ports (including Canton and Shanghai) opening to foreign trade and confirmed the 1841 transfer of Hong Kong Island to the British.

Situated on the banks of the Huangpu River, Shanghai was an unwelcoming mass of marshy, malarial, mudflats — quite similar to the archipelago of seven islands that the city of Bombay once was — but it offered the best access to the Chinese market: Hong Kong was overcrowded and the locals in Canton hostile to foreigners after the war. Shanghai’s location on the north east coast of the Chinese empire was also a factor in its success as it was at the cross-roads of both the Chinese, and the newly opened Japanese markets.

According to one account of this early period, the first to arrive in Shanghai were 50 British traders with their wives. A few American traders followed, and by 1850, there were a few Parsi merchants and a Jewish one, Elias Sassoon, from Bombay. [6]

It was during this period that two very significant changes took place in Bombay’s China trade. A few prominent traders — like David Sassoon, Sons and Company, and Tata & Co, from Bombay [7] — monopolised it. Now, both the Sassoon and Tata firms opened branches in the Japanese ports of Kobe and Yokohama, while keeping Shanghai as their base in the Far East.

Secondly, the merchandise mix of the trade between Bombay and China became more varied. It now included, cotton yarn from Bombay’s mills, textiles, spices, muslin, metals, camphor, indigo, dates, woollens, and teakwood.

The Shanghai Bund

One enduring legacy of the Bombay-China trade is the Shanghai Bund, an embanked quay that is today an upscale commercial and residential area. By the 1930s, most of the property on the Bund (part of the international settlement) was owned by the Bombay headquartered E.D. Sassoon & Company, and by employees of this firm in China who had opted to open their own businesses, like Silas Hardoon and the Kadoorie family (now living in Hong Kong).

Unfortunately, this branch of the Sassoon family (headed by the great-great grandson of David Sassoon, Sir Victor) miscalculated the turn of events in China’s long raging civil war (1927-1950). Having shifted the headquarters of E.D. Sassoon & Co. from Bombay to Shanghai on the eve of Indian independence in 1947, Sir Victor had to shift headquarters yet again from Shanghai to the Bahamas, with the Communist Party of China’s takeover of Shanghai.

The re-emergence of Shanghai with the opening of the Chinese economy in the 1980s; as the headquarters of the new BRICS Bank; its glorious restoration of heritage buildings on the famous Shanghai Bund — the former Sassoon-owned Cathay Hotel is today the Fairmont Peace Hotel — and the aim to convert the city into an international financial centre by 2020, augurs well for this city.

In fact, the Shanghai road map to financial pre-eminence mirrors Mumbai’s road-map to becoming India’s second global financial centre. What Mumbai needs to mine from the Shanghai model is the way this city has resurrected its financial history, albeit a colonial one, and restored its heritage buildings to milestone this past.

Sifra Lentin is the Mumbai History Fellow at Gateway House.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2016 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited

References

[1] http://ndb.int/brics-leaders-speak-on-the-new-development-bank-in-goa.php#parentHorizontalTab2 (Accessed on October 18, 2016)

[2] http://ndb.int/NDB-MEMBERS-OF-BRICS-INTERBANK-COOPERATION-MECHANISM%20.php#parentHorizontalTab2 (Accessed on October 18, 2016)

[3] The term ‘colonial’ is used loosely here as Shanghai was, strictly speaking, never a colony. Property along the banks of the Huangpu river were given by the Chinese to the English, French and Americans as ‘concessions’ much like a diplomatic enclave, which gave its residents immunity from Chinese laws.

[4] Greenberg, Michael, British Trade And The Opening Of China 1800-42 (UK, Cambridge University Press, Reprint 2008), p. 6.

[5] Thampi, Madhavi, and Shalini Saxena, China and the making of Bombay (Mumbai, The K.R. Cama Oriental Institute, 2009), p 40.

[6] Jackson, Stanley, The Sassoons (London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1968), p 23.

[7] Thampi, p. 42

[8] http://www.strategyand.pwc.com/media/file/Shanghai_2020_en.pdf (Accessed on October 19, 2016)