This is the first in a four-part series on Partition. Read the next one here.

This is the platinum jubilee year of India’s independence from British rule – and the country’s Partition, which resulted in the most large-scale migration of 20th century history: 15 million people crossed to and fro.[1]

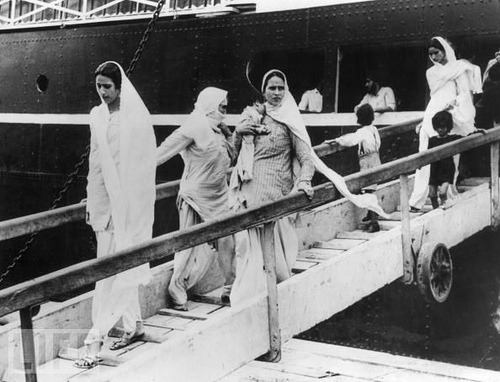

The approximately 1 million refugees [2] who came by sea to Bombay, leaving behind home and property, carried with them memories of Sindh, its cities (Hyderabad, Shikarpur) and its vibrant capital, Karachi, once considered Bombay’s twin. The reasons for the strong similarity between Bombay and Karachi were many. Both cities were once joined by a common colonial history – Sindh was part of Bombay Presidency from 1847-1936 and governed from its island capital city – economy, trading communities and a cosmopolitan milieu.

Karachi, Sindh: a gateway to prosperity

Karachi city and its port were as much a colonial creation (though 200 years later) as the city of Bombay and its docks were. If Bombay was the gateway to India, Karachi port and harbour were, geopolitically, the gateway for the British to Central Asia and Afghanistan. The Talpur (Balochi) rulers of Sindh [3] were willing collaborators in the Malwa opium trade that bypassed the tariffs of Bombay Presidency by being conducted via caravans from Malwa (in Central India) through the Thar desert into Sindh, and by sea from Karachi to the Portuguese ports of Diu, Daman and Goa, before proceeding to China. Malwa opium was cheaper and outsold British-controlled Bengal or Patna opium in the Chinese markets. Many of Bombay’s successful 19th-century merchants were actively engaged in the Malwa trade, transiting through Karachi to Portuguese ports, where their country ships [4] lay anchored to load the precious cargo.

Karachi came under British rule in 1839, followed by the region of Sindh in 1842: by 1847, Sindh had become part of the Presidency of Bombay. It is from this period onwards that the fluencies between the two cities began, with one big difference: Karachi port soon turned into the preferred destination for the grain trade of Punjab, and, in fact, for trade in North India, in general. [5]

This triggered the growth of financial institutions, markets, the establishment of a Royal Indian Navy base at Manora Island, south of and part of an archipelago sheltering the natural harbour of Karachi, and social institutions, such as clubs, all of which was almost parallel to Bombay’s own growth. Most importantly, Karachi too acquired a mix of trading communities. There were Parsis, Jews, Armenians, Christians, Bhatias, Banias, Marwaris, Memons, Bohras, Khojas, along with local Sindhi traders, like the Sindhi Lohanas – both Hindu and Muslim – who dominated its cotton trade.

In an article, ‘Sassoons and the Doongursees: a Relationship’, Pushpa D. Bhatia (nee Doongursee), recalls how her grandfather Seth Doongursee, broke away from the family business in Bombay to start something on his own in Karachi. The Doongursees in Bombay were the sole cotton brokers and mukaddams for the E.D. Sassoon Mills, whose personnel naturally appointed someone they knew – Seth Doongursee – to handle their import and export trade at Karachi in 1901. In much the same way, other companies, businesses, and banks, headquartered in Bombay, had also opened offices in Karachi because of its growing commercial importance

With the shadow of Partition looming large – it was to be reality after Lord Mountbatten’s announcement on 3 June 1947 – many immigrant trading communities from Bombay Province who had made Karachi and Hyderabad (Sindh) their home, began sending their families back. What was moved out too, by early July the same year, was an estimated sum of Rs 200 to 300 million to banks in Bombay and Delhi. According to one study on Partition, “Muslim politicians were anxious to stem this flood (of capital) and to ensure that the wealthy Hindu elite retained their role in the city’s and province’s economic life, but reports of violence in Punjab in the weeks after Partition unnerved many; and by mid-September around 1,000 persons a day were departing by boat for Bombay and the Kathiawar.”[6]

The Sindh Legislature was the first to vote to join Pakistan, largely on the understanding that the Muslim League’s 1940 resolution spoke of a federal set-up that would give a great degree of autonomy for its provinces, and hence secure their ethnic identity. But this expectation was belied: the emerging political and security concerns regarding the India-Pakistan border led to the eventual imposition of the policy of One Unit (a strong central government), in 1956. [7]

Contrary to popular perception, not all Hindu Sindhis fled to India: there still exists a presence in Sindh of 1.98 million, according to a Pakistan census of 1998. [8] However, what triggered the bulk of the community to leave was the eruption of riots in Quetta (August 1947), followed by communal disturbances in the cities of Nawabshah (November), Hyderabad-Sindh (December), and finally in Karachi, in January 1948. [9]

Making Bombay home

The Hindu Sindhis from the former British Province of Sindh were the largest community of refugees to make Bombay their new home. It was only natural that they should take the sea route from Karachi, a mere 589 nautical miles away, and the safest way across the Radcliffe Line, which carved up the subcontinent into two nation-states.

For the more affluent, who had business and family in Bombay, the transition was easier. Most, though, had it tough. Yet, the community is today known for its spirit of enterprise and contribution to the building of modern Bombay. Where they once strained the limited housing and infrastructure of the city, Sindhi builders, like the Hiranandanis, have constructed huge townships. Sindhi colleges under the umbrella of the Hyderabad (Sind) National Collegiate Board are considered among the most progressive in the city for their introduction of globally relevant academic courses.

Alongside the Sindhi influx into the city, were Punjabis, Sikhs and refugees from the North West Frontier Province, who constituted about 5% of the total number, those who had chosen to travel via the Sindh and Karachi route rather than cross the dangerous land border.

Refugees in Bombay were housed in camps on Queens Road (on the Japanese Gymkhana grounds, located between PVM Gymkhana and the Nariman buildings opposite Cooperage Gardens)[10]; along Frere Road (today’s Shahid Bhagat Singh or Dockyard Road behind the General Post Office); at Sion-Koliwada, where mostly refugees from Punjab and the North West Frontier Province stayed; and at a sprawling camp called Ridley’s Siding (lit. a railway siding), just beyond Kalyan Station, which, because of its Sindhi population and the river on whose banks the camps were built, was called Ulhasnagar (or ‘city of joy’). [11]

The Bombay government’s funds were stretched, resulting in difficult living conditions in the camps in Bombay as also those across Bombay State (Poona, Thana, Ahmedabad), but it ensured that there was peace in the financial capital by appointing an old Sindh hand, Jamshed Darabshaw Nagarvala (Indian Police), as head of the Special Branch CID, Bombay. J.D., as he was popularly known, spoke and wrote Sindhi fluently, a mastery he had gained during his postings in Upper Sindh, and later, as district superintendent of police in Karachi, and his presence was vital to maintaining peace between the host population and the newcomers. The Annual Report of the Greater Bombay Police (1948, 1949, 1950) lists everything from minor skirmishes (unpaid bills at restaurants) to mini riots that took place during the peak years of the refugee influx.

Viewed in hindsight, these now seem like inevitable rites of passage for a community that enriched Bombay variously. Bombay lost its twin, Karachi, whose demographics and socio-cultural ethos changed irretrievably, but gained much through the people who came to its shores.

Sifra Lentin is Bombay History Fellow at Gateway House.

This is the first in a four-part series on Partition. Read the next one here.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in or 022 22023371.

© Copyright 2017 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References

[1] Talbot, Ian, and Gurharpal Singh, The Partition of India (New Delhi, Cambridge University Press, 2009), p.2. To date there is no agreement on the number of people who died during Partition.

[2] Figures regarding refugees in Bombay and its surroundings vary. However, two recent books pin the Hindu Sindhi refugees to India between 1.2 to 1.4 million, of which the majority came to Bombay port, although many disembarked at Okha, Navlakhi, Porbander, and Veraval on the Kathiawar (Kutch) Coast.

Bhavnani, Nandita, The Making of Exile: Sindhi Hindus and the Partition of India ( Chennai, Tranquebar Press, 2014), p. 169. Also: Aggarwal, Saaz, Sindh: Stories From A Vanished Homeland (Pune, Black-And-White Fountain, 2012), p. 134.

[3] https://www.britannica.com/place/Karachi

[4] Country ships were large ships specially built at Bombay and Calcutta dockyards to carry cargoes of raw cotton. Alongside, its legitimate cargo of cotton bales, they also carried opium (a banned substance) to China.

[5] The Punjab emerged as the granary of India in the 1890s, and Karachi port became the region’s principal outlet. By 1914, it had become the largest grain exporting port of the British Empire.

[6] Talbot , Ian, and Gurharpal Singh, The Partition of India (New Delhi, Cambridge University Press, 2009), p. 121.

[7] Rajagopalan, Swarna, State and Nation in South Asia (USA, Lynne Reinner Publishers, 2001), p. 134. For a more detailed background on the same: Shah, Mehtab Ali, The Foreign Policy of Pakistan: Ethnic Impacts on Diplomacy 1971-1994 (London, I.B. Tauris, 1997), p. 49-51.

[8] Pakistan Census 1998 www.pbs.gov.pk/sites/default/files/other/yearbook2011 (accessed on 14.8.17). Also, according to the Pakistan Hindu Council, approximately 94% of Hindus in Pakistan live in Sindh Province and about 4% in Pakistan Punjab. In Sindh Province they constitute 17% of the population. pakistanhinducouncil.org.pk/?page_id=1592 (accessed on 14.8.17).

[9] Aggarwal, Saaz, Sindh: Stories From A Vanished Homeland (Pune, Black-And-White Fountain, 2012), p.132-33.

[10] Queen’s Road once extended all the way up to the Indian Navy Sailors Institute, Sagar.

[11] The Ulhasnagar-Kalyan Camp originated from pre-existing abandoned Second World War military barracks.