The choice of Zanzibar[1] off the east coast of mainland Africa, as the location for the first overseas campus of the premier Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Madras, is redolent with the centuries-old ties of these islands with the Indian subcontinent’s west coast, and by the 19th century, the islands of Bombay. The Memorandum of Understanding to establish an overseas branch was signed during the official visit of External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar to Tanzania from 5 to 8 July. Establishing an IIT campus in Zanzibar will be a game-changer not just for Tanzania, but also for all African nations, as it is expected to develop into a major hub for technology education for the continent.[2]

The ancient links with the west coast of India and East Africa, and Zanzibar in particular, began with trade during the 16th to 18th centuries. The independent Kutch and Saurashtra ports, and the Mughal port of Surat, had mercantile ties with the Gulf and Red Sea Arabs and expanded to the East African coast as far south as Mozambique[3]. India exported textiles[4], indigo, wheat, rice, and leather goods, while Zanzibar supplied slaves[5], small quantities of ivory, and gum copal to these kingdoms.

Indian merchant immigration to Zanzibar began[6] later, via Oman in the 17th century, when Zanzibar, the Mrima coast[7], and Mombasa came under Omani hegemony. Omani Arab and Indian settlements in Zanzibar were spurred by the Portuguese entry into the Indian Ocean world in the 15th century. It was the Portuguese aggression in monopolizing the East African trade in slaves, gold, and gum copal, through a policy of acquisition and fortification of strategic ports[8] that brought them into confrontation with the Ottoman, Arab and Indian rulers, and merchants, who dominated this trade.

But the Omanis[9] retained their dominance, as did the Indian merchants. By the 19th century, the corridor between India and Africa had grown commercially, with Bombay and Omani Zanzibar and its mainland Mrima Coast[10] being particularly active. In 1819, the Indian population of Zanzibar numbered 214 and by 1839 it was 900.[11]

Their primacy in the country’s trade began when Jairam Sewji, advisor to the Omani sultan and then the wealthiest Bhatia merchant of his time, became the customs farmer[12] of Zanzibar in 1819, followed by that of the Mrima Coast in 1837. By the early 19th century, Kutchi-speaking Indian merchants, drawn from both Hindu (Bhatia, Lohana) and Muslim communities (Khoja, Bohra, Memon) were privileged collaborators of the Omani sultans. The Bhatia merchant Sewjee Topan (1764-1836) was an influential figure in the court of Seyyid Said, as was his son Jairam, who succeeded him at the court. It was Jairam who advised the Sultan to transfer his capital from Muscat to Zanzibar to better control the slave trade there vis-à-vis the Portuguese slave trading hubs in Mozambique and its hinterland. When the Omani capital shifted from Muscat to Zanzibar in the years 1832-40, they moved with Sultan Seyyid Said. Jairam was also a crucial player in encouraging greater migration from Kutch to Zanzibar.

Other communities followed. Repeated droughts in Kutch and Saurashtra compelled communities there to seek their fortunes overseas or move south to Bombay, which was now dominating the coastal trade that these merchants were active in[13]. Leading Khoja merchant Allidina Visram was urged by H.E. Mahommed Shah Aga Khan III, who first visited Zanzibar in 1905, to persuade more Aga Khani Khojas to settle in East Africa.

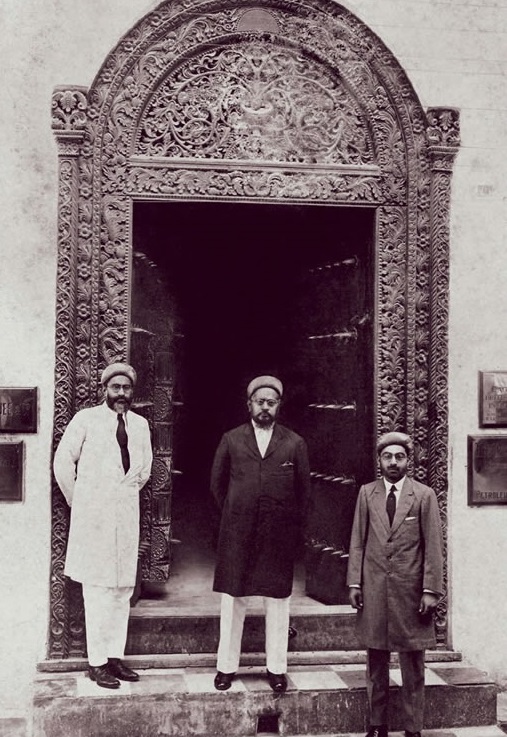

These Indian expatriates resided in Zanzibar’s Stone Town, today a UNESCO World Heritage site. Their Indian influence remains. The intricately carved heavy wooden doors of most Stone Town homes were executed in Kutch. The height, weight, and intricacy of carvings on these doors were an indication of the wealth of the merchant who resided there. The Sultan’s sea-facing palace is part of Stone Town and underscores how much the Sultan valued his Indian advisors and their importance to Zanzibar’s economy. By the 1840s, Indian capital underwrote the caravan trade into the East African interior and lent to foreign trading houses in Zanzibar. In 1842, the American agent R.P. Waters borrowed Maria Theresa Thaler (MT $) 115,000 from Indian traders to finance American purchases, of which 85% was lent by the top five merchants. This was just one of many transactions they contracted with foreigners in Zanzibar.[14]

Bombay’s centrality to this trade was secured by the establishment of a British Consul and a consular court in Zanzibar city in 1841, for settling disputes between Indian merchants and the foreign trading houses from the United States, Germany, France, and Belgium.[15] Appeals from the consular court were heard in the Supreme Court of Bombay. The Indian rupee was a popular currency in Zanzibar, although high-value trade was often contracted in the Austrian Maria Theresa Thaler. This indicated growing British influence in Zanzibar because of the trade with British India.

Bombay and its port soon became the third corner of the Zanzibar-Bombay-London triangular ivory trade. Ivory exported from Zanzibar to London instead of being directly shipped would arrive in Bombay before being re-exported. East African ivory was famous for its malleability and colour and was used for piano keys, hair clips, and cutlery handles. The ivory trade’s upswing coincided with the final abolition of slavery when Zanzibar’s Sultan Barghash signed the Anti-Slavery Treaty of 1873 with Great Britain. With its end, slaves from East Africa began to be utilized to carry ivory to the coast for export overseas, and as labour in local clove plantations, where many Indian merchants diverted their capital as money lenders to Arab plantation owners.

It marked a turning point in Indian immigration too: Zanzibar’s Indians began looking to the mainland for opportunities because of the decline in Zanzibar’s economy. The overproduction of cloves resulted in a steep fall in export prices, and competition from West and North African ivory exports reduced supplies from East Africa. The 1905 takeover of the Imperial British East Africa Company’s territory by the British government in what became British East Africa (present-day Kenya), followed by its takeover of Uganda, and the formation of German East Africa in1891[16], made Zanzibar, which by then came under British rule, a natural gateway for Indian merchants into mainland East Africa.

The population of Indian origin people in today’s Tanzania, including Zanzibar, is small, about 50,000[17] compared with the peak of around 110,000[18] at the time of independence in 1961. Africanization and nationalisation of homes and businesses in the late 1960s and 1970s led to the large-scale immigration of Indians to the U.K. and Canada, making them double immigrants like the legendary British Parsi singer Freddie Mercury, who was born in Zanzibar. Oman today has an old community of Kutchi-speaking merchants some of whom also speak fluent Swahili, a living legacy of India and Zanzibar’s historic ties via Oman.

Hopefully, the choice of Zanzibar as the first overseas location of IIT Madras will prove as propitious for a network of Indian higher education institutes in East Africa as it once did for its Indian trading communities.

Sifra Lentin is Fellow, Bombay History, Gateway House

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here

Support our work here.

For permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in

©Copyright 2023 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorised copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References

[1] The archipelago of Zanzibar also includes the islands of Pemba to its north. Historically, the islands of Pemba were always differentiated from the islands of Zanzibar although both island groups were once ruled by the Omani sultans. Today, Zanzibar, with the Pemba islands, form a semi-autonomous region of the United Republic of Tanzania.

[2] The first batch of 70 students begin classes in October 2023. There are only two degrees being offered: a four-year Bachelor of Science and a two-year Master of Technology in Data Science and Artificial Intelligence. See: https://www.outlookindia.com/national/iit-tanzania-campus-to-offer-data-science-and-ai-courses-classes-to-start-from-october-news-301721 (Accessed on 24 July 2023)

[3] The coasting trade between the coastal kingdoms of Sindh, Kutch, and Kathiawar (today’s Saurashtra in Gujarat) with the Gulf kingdoms and the East African coast, is dated much earlier. The existence of a mosque for Arab traders built by the Solanki Jain rulers in Bhadreshwar (Kutch), which is dated as early as the 11th century and is believed to be the first (still standing) mosque in India and one in Khambhat of the same vintage, point to an active maritime trade in the North Arabian Sea during the medieval period. Jains were prominent in the medieval trade with Mozambique and Kilwa. [Mehta, Makrand. “Gujarati Business Communities in East African Diaspora: Major Historical Trends.” Economic and Political Weekly 36, no. 20 (2001): 1738–47. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4410637. (Accessed on 9 August 2023)]

[4] The Kiswahili terms Bafta and Kaniki, which are still in use, have their origins in local Gujarati names for a particular quality of cotton cloth.

[5]A significant presence of the African-origin Sidi communities in Kutch and Saurashtra is a living legacy of the slave trade.

[6] It was largely confined to merchants and their male staff, as women and family were kept home in Sindh, Kutch, and Saurashtra, regions from which these merchants hailed. The Muslim Bohra and Khoja merchants who immigrated in the early 19th century often brought their families with them.

[7] The Mrima Coast extends from Tanga on the mainland opposite the Pemba archipelago, to the Rufiji River. The Portuguese string of ports strategy across the East African littoral, the Persian Gulf, the Subcontinent, South East Asia, and the Far East, was aimed at control of maritime trade keeping in mind the limited manpower that Portugal possessed. Moreover, they introduced the Cartaz, a paid pass, for traversing through their territorial waters, which made them unpopular as the Indian Ocean trade prior to the Portuguese entry functioned on the principle of open seas. See https://www.gatewayhouse.in/portuguese-string-of-ports/

[9]The first serious pushback to Portuguese power in the Arabian Sea trading arena came from the Omani sultans. Omani successes in wresting back strategic ports from the Portuguese were outstanding: Muscat in 1658, Mombasa twice in 1698 and then 1729, and the islands of Zanzibar and Pemba in 1698.

[10] The Mrima Coast extends from Tanga on the mainland opposite the Pemba archipelago, to the Rufiji River.

[11]Sheriff, Abdul, Slaves, Spices & Ivory in Zanzibar: Integration of an East African Commercial Empire into the World Economy, 1770-1873 (Ohio, Ohio University Press, 1987), pp. 84 and 114 (endnote 55)

[12] A customs farmer is an archaic legal term for a person appointed by the crown to exact and collect customs duty at a particular port. In return, the customs farmer receives consideration in the form of a farm (an arrangement whereby one rents the income that derives from a revenue stream) for a fixed period. For this the customs farmer pays the Crown a lumpsum payment.

[13] See https://www.gatewayhouse.in/globalised-dawoodi-bohra-bombay/

[14] The top six Indian merchants in this transaction were Jairam Sewji, Mohammad b. Abd al Kadir, Isa Abd al Rahman, Bandali Bhimji, Virji-Kanu-Kasu, Topan Tajiani. [Sheriff, Abdul, Slaves, Spices & Ivory in Zanzibar: Integration of an East African Commercial Empire into the World Economy, 1770-1873 (Ohio, Ohio University Press, 1987), p. 98.]

[15] Not all Indian merchants in Zanzibar began in business with capital like the Sewjee family. Many prospered due to the trade with American trading houses, which advanced short-term capita these merchants to procure goods on a timely basis when their ships anchored at Zanzibar.

[16] German East Africa included the territory of mainland Tanzania, Burundi, Rwanda, and the Kionga Triangle, which was later incorporated into Mozambique. After the First World War, German East Africa was divided between Britain, Belgium, and Portugal and was reorganized as a mandate of the League of Nations.

[17] People of Indian Origin are 50,000, and Non-Resident Indians are 10,000 in Tanzania. See https://mea.gov.in/population-of-overseas-indians.htm (Accessed on 9 August 2023)

[18]Bertz, Ned, Indian Diaspora in Tanzania, https://oxfordre.com/africanhistory/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277734-e-987;jsessionid=47F51236EB8010E082FC10CFDF43C33A?rskey=y7R5ib&result=197 (Published online on 26 May 2021)