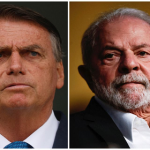

On October 30, 2022, more than 120 million Brazilians will head to the polls for the second round of elections to select their next President. This is the first time that a late-term president – Jair Bolsonaro- has sought re-election and his main opponent is a former president – Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

This election is Brazil’s most contested and polarizing race. In the first election round, Lula received more than 57 million votes. That corresponds to 48% of all valid votes, putting him in first place, but not enough to prevent a runoff on October 30.

On his part, Bolsonaro has to overcome a gap of over 6 million votes. Lula has brought the third and fourth place candidates – Ciro Gomes and Simone Tebet – into his broad alliance against Bolsonaro. Lula is still the favourite to win the runoff, but his advantage depends on the additional force of the coalition, and it will be necessary for the collation to negotiate some adjustments in his economic agenda. The most sensitive points include the commitment to fiscal balance, a point repeatedly criticized by Lula’s economists, along with the maintenance of labour law reforms and not resuming economic policies considered interventionist.

When he was president, Lula blended foreign policy and economics,[1] championing diplomacy as an instrument of economic development and the consequent preservation of the country’s autonomy through a diversification strategy[2]. Precisely, this means the adherence to international norms and principles by means of South-South and regional alliances and through bilateral agreements with non-traditional partners -China, Asia-Pacific, Africa, Eastern Europe, Middle East and others. The goal was to reduce asymmetries in external relations with powerful countries. As a result, Lula pushed for South-South cooperation by proactively reaching out to strategic partners in developing countries, to gain more bargaining power in international negotiations. The long-standing tradition of attracting allies and support through soft power, emphasising cooperation, multilateral initiatives and diplomacy, combined with a flourishing economic performance, resulted in an increase of Brazilian influence in international affairs in the early 20th century.[3]

Domestically, Lula’s administration performed well, with a rising economy and reduction in inequality. The Workers Party leader left office with an 83% approval rating[4] and consequently, was able to influence the election of his successor, Dilma Rousseff, the first woman President of Brazil.

The downturn for Brazil’s began in 2013 with mass protests and riots throughout the country over corruption scandals involving the state-run oil giant, Petrobras. This undermined Roussef’s approval ratings, leading to her being ousted from the presidency in 2016. Lula was imprisoned in April 2018 for corruption and money laundering, in an order by the controversial judge Sergio Moro[5]. Moro’s decision was upheld by an appeal court. Lula has always proclaimed his innocence and argued the case against him was politically motivated.

Consumed by a desire to redeem himself after being released, Lula positioned himself as a candidate. He claimed to have no regrets, despite knowing that he was arrested and could not run in 2018. It returned him to centre stage in Brazil and put him back on track for disputing the 2022 elections.

On his part, Bolsonaro lost centrist support after his mishandling of the Covid-19 pandemic. Added to it was his lack of empathy with Covid-19 victims and continuing insistence that the electronic ballot boxes were prone to fraud. His support is strongly in defence of conservative agendas, such as opposing abortion, same-sex marriage, traditional family values and is still strong as is his approval rating, guaranteeing him a considerable share of votes. However, the fact is that Brazil has also performed poorly, economically, over the past four years.

The key to Bolsonaro’s popularity is the combination of a successful alliance with the Brazilian National Congress status quo (centrão), a significant pro-market agenda and the backing of right-wing supporters. Along with this base, the agricultural and financial industries are likely to remain a cornerstone of his administration’s political strategy in a second term as his administration implemented many policies around liberlising the purchase of guns, titling of public owned lands and privatization of state-owned enterprises. Nevertheless, some of the policies, such as the liberalisation of mining on indigenous lands, triggered illegal activities and clandestine logging, as well as land-grabbing, all of which has affected the international image of the country.

Bolsonaro has significantly shifted away from traditional aspects of Brazilian foreign policy and certainly from Lula’s policies in terms of multilateralism, international cooperation, and the upholding of democratic liberal values.[6] His anti-globalist and anti-communist worldview, intertwined with a religious discourse, gained internal support. The attack on China only resulted in dissatisfaction on the part of exporters and agribusiness.[7]

Bolsonaro’s political alignment with President Trump went far beyond the economic considerations in Brazil-U.S. bilateral relations, as the two leaders built strong roots on ideological terms. This said, the Brazilian administration adapted his discourse and maintained a level of pragmatism on the role of BRICS in the world. China continues to be the country’s biggest trade partner and Brazil maintains strong ties with Russia, especially the dependence on ammonium nitrate imports, crucial for Brazilian primary goods exports. Even though Brazil voted in favour of the United Nations (UN) resolution that rebuked the war in Ukraine, the country has criticized the application of indiscriminate sanctions against Russia and stated that the measures do not lead to a reconstruction of dialogue.

Since 2019 the India-Brazil strategic partnership has also been revitalised by meetings between Prime Minister Modi and Bolsonaro, which took place not only in multilateral organisations, such as the annual BRICS summit, but also in their respective capitals. In January 2020, Bolsonaro was invited as the Chief Guest to India’s Republic Day celebrations. Overall, the countries historically share common interests in pharmaceutical and technological exchanges, as well as energy and food security.

Brazil was the first Latin American country to start diplomatic relations with independent India in 1948. Throughout the 20th century, India and Brazil advocated for a role of being primary protagonists, moving away from a secondary role in global governance, especially in the UN.

Brasilia and New Delhi have developed policies, institutions, and governance in pharmaceutical, IT, along with cooperation in fiscal and monetary areas.[8] These are of great relevance to inclusive and stable economic development. For continued prosperity, both countries can deepen collaboration in health and vaccines and under multilateral forums such as BRICS, and IBSA, and especially now, when India and Brazil will be consecutive Presidents of the G20 in 2023 and 2024.

Whether Bolsonaro or Lula return to power, both will continue in these common interests with India. The legacy of more than 70 years of Brazil-India relations and the pragmatism towards a multipolar world are more likely to prevail in a future scenario for two of the biggest democracies on the planet.

Marcel Artioli is researcher at the Center for International Studies and Analyses (NEAI) of the Institute of Public Policies and International Relations (IPPRI) of the São Paulo State University.

Carlos Eduardo Carvalho is Professor at the Department of Economics of the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo (PUC-SP), and at the Graduate Program in International Relations San Tiago Dantas (UNESP – Unicamp – PUC-SP).

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here

For permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in

©Copyright 2022 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorised copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References

[1] http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0034-73292010000300002&lng=en&tlng=en

[2] https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01436590701547095

[3] https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01436597.2012.674704

[4] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2010-12-19/brazil-s-lula-leaves-office-with-83-approval-rating-folha-says

[5] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-56326389

[6] https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09557571.2021.1981248

[7] https://academic.oup.com/ia/article-abstract/97/2/345/6159425

[8] https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Marcel-Artioli/publication/348807026_CHAPTER_3_FISCAL_FEDERALISM_CURRENCY_AND_BANKING_OF_THE_POOREST_FOR_SUSTAINABLE_AND_INCLUSIVE_DEVELOPMENT_A_RESEARCH_AGENDA_FOR_INDIA_AND_BRAZIL/links/63388bcf769781354eaec929/CHAPTER-3-FISCAL-FEDERALISM-CURRENCY-AND-BANKING-OF-THE-POOREST-FOR-SUSTAINABLE-AND-INCLUSIVE-DEVELOPMENT-A-RESEARCH-AGENDA-FOR-INDIA-AND-BRAZIL.pdf