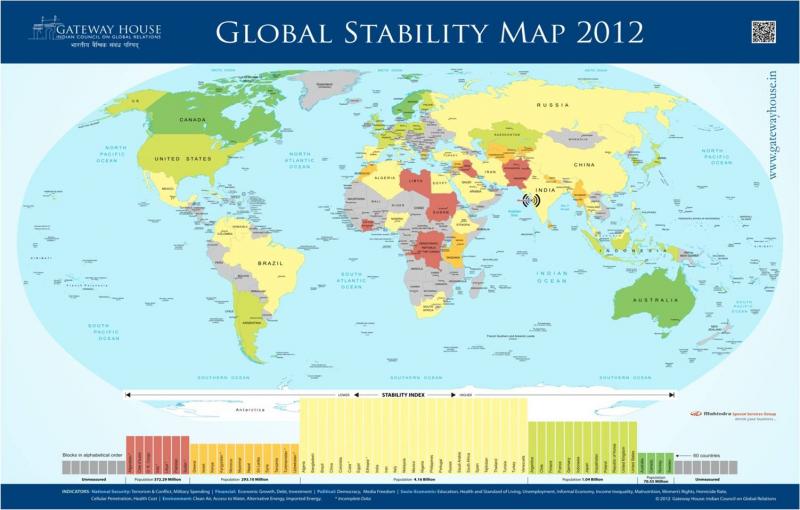

In 2012, Gateway House conducted a study of 60 countries using 20 different socio-economic indicators to assess the mid to long-term stability of a country and visualized it on a map. Based on the data, countries were classified under varying levels of stability ranging from “Unstable” coloured in red to “Stable” coloured in green. Both Brazil and India were assessed as countries of “Medium” stability and coloured in yellow.

Gateway House’s Global Stability Map, 2012

At the time, the assessment seemed odd. Brazil has a per-capita income of $11,340 [1] – seven times that of India’s, a population of 200 million – one-sixth that of India’s, and the wealth of energy, mineral and food resources. Most roads in Brazil are like Europe, many health care centres are like corporate offices, and land is rich and fertile for as far as the eye can see. So, it just seemed unfair to equate the two.

It was not until my recent trip to Brazil that the similarities between India and Brazil became evident.

Brazilians took to the streets in June 2013 to protest against the hike in transportation fees and lack of education and healthcare. It took the government and world by surprise. The government’s initial heavy-handed approach only encouraged the angst to accelerate into multiple movements with greater spirit and speed. Last week’s protest by the teachers union to demand better funding for education by “occupying” the House of Councilors of Rio de Janeiro is only the latest of the series.

There is a demand for seeking a deeper democracy and a greater public voice in it. The frustration with the government is as acute as the endearing pride that Brazilians feel in the freedom to protest in a democratic country. The threat of the protests being hijacked by political agendas is continuously being countered by the tech-savvy distributed nature of the protests that does not offer leaders the chance to co-opt the opposition. Comparisons with protests in Turkey, Egypt or even India are dismissed quickly. But many in Brazil associate with the same hardships that arise from inequality, the yearning for direct and swift democracy, and the fight for dignity that is happening simultaneously in other countries.

The underlying development approach is also being challenged. Closing 50 schools to divert money for a sports facility in Rio is unacceptable. The comparative advantage theories of globalization have meant that large sections of the population have lost skills or opportunities to work in the traditional jobs they used to. Large-scale, automated, high-yield farming is a rich profession, as it is with most American or European counterparts. The visual of the large slums on the outskirts of Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, and the high electrically-fenced homes of the wealthy, are evidence of increasing inequality and crime.

Despite these domestic challenges, Brazil has been playing a leading role in world affairs. At a recent BRICS conference organized by ANPOCS, the National Association of Research and Graduate Programs in the Social Sciences in Brazil, many foreign experts, including me, spoke highly of the Bolsa Famila programme that combines cash transfers with education and health. It is a development model for the world to emulate.

The caution only came from the domestic experts who questioned their activism in world affairs given that there is so much to be done at home. Hosting the FIFA 2014 and Olympics 2016, are already being widely questioned. Brazil just became the only emerging country to publicly repudiate the US spying programme by calling off a state visit with President Obama before the 2013 UN General Assembly in New York – a virtuous move but with uncertain benefit. Earlier in 2011, it became the only emerging country to offer to bail out Europe at the height of the crisis in 2011 – again an ambitious offer without clarity on return.

A lot depends on how focused, swift and even its approach is towards reforms. So far the government has only made incremental progress on the promises it made in June. Some expenses for the FIFA World Cup have been put on hold, an auction for the expensive bullet train between two of the biggest cities Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo, has been put on hold, a new policy to encourage doctors to serve in rural areas has been in place, and A referendum for political reforms has yet to take place.

However, any early prognosis of Brazil as a failed state should be dismissed. The Economist cover story for September 2013 titled, “Has Brazil blown it?” is a case in point. Its clinical and scathing evaluation of the economy undermines the spirit of a hard working culture and desire for globalization.

This zeal for a greater voice in its democracy, the questioning of developmental priorities and the ambition of playing a greater role in world affairs, is heartening and healthy for a growing country. As it goes through its evolution, the similarities with India will converge.

Akshay Mathur is Head of Research at Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations.

This blog was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.

© Copyright 2013 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited

Reference

[1] The World Bank. (n.d.). GDP per capita . Retrieved from http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD