This article has been adapted from a speech, titled, ‘China’s geoeconomic imperatives and their manifestation in the IOR’. It was delivered at a seminar on ‘An assessment of Chinese presence and initiatives in the IOR’, organised by the Western Naval Command, in Mumbai, on August 17.

Economic expansion

The Indian Ocean Region (IOR) extends from the East Coast of Africa to South East Asia, including Indonesia to our east and Australia in the south east, that is, the Arabian Sea to the west and the Bay of Bengal to the east. India sits at the centre of this vast and populous region where China is aggressively expanding its presence. China, under President Xi Jinping, has abandoned Deng Xiaoping’s (1978-1989) “hide and bide” policy, which sought to put a conciliatory, non-threatening face on its rapid economic rise, for an aggressive, money-fuelled drive for global influence.

To give some perspective to this historically unprecedented rise: between 1979 and 2016, the Chinese economy expanded 62 times – from less than $200 billion to approximately $11 trillion. It became the world’s largest exporting nation in 2009, the world’s largest trading nation by 2013, and is set to overtake the United States as the world’s largest importer of fossil fuels.

China entered into long-term agreements with countries like Australia and Saudi Arabia for import of fossil fuels, iron ore and other raw materials to process as it evolved into the ‘world’s factory’. Correspondingly, it also had to secure markets for its rapidly growing production of cheap consumer goods. The long logistic chains, centring on China, have generated the backward and forward linkages that have fed the dependencies on the Chinese economy, especially of major commodities-exporting countries in Africa and South America.

In the early phase, China offered numerous concessions to attract Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) from Hong Kong, the Chinese Diaspora and western MNCs, but today, it is the third largest global investor in the world, after the U.S. and Japan.

Global imperatives

The speed and scale at which the Chinese economy grew had both a regional and global impact. China expanded its presence globally to safeguard and promote its continued access to markets and to secure energy flows. At the same time, economic expansion gave it increasing political influence and fed its ambition to be recognised as a superpower. That pursuit translated into several priorities, starting with sustaining a globalised world of free open markets, as spelt out by President Xi at Davos in January earlier this year.

A second global priority is a clean environment, another area where China seeks a leadership role after Trump threatened to withdraw the U.S. from COP21.

A third priority which China started implementing through participation in anti-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden was to ensure the free flow of trade and secure access to energy supplies, and, more recently, to protect the massive investments it has made all over the world.

The other superpower?

Chinese President Xi Jinping’s call in June 2013 for a “new model of great power relations”, equating his country with the U.S., drew a suitably wary response from then President Obama. But that did not hold China back from beginning to act like the other superpower – identifying regional interests in the exercise of its growing economic weight. With its growth rates starting to moderate from double digits to around 6% currently, it adopted policies to upgrade its value-add by producing technologically more sophisticated products and gradually increasing the proportion of consumption of its GDP. The implementation of these policies had two major implications:

- Firstly, with its own construction boom winding down, China sought to export its massive overcapacity in steel, cement, and engineering skills, financed by accumulated foreign exchange reserves, approximating $4 trillion. In 2013, President Xi aggregated construction projects being undertaken by its companies abroad into the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which has become his government’s signature programme.

- Secondly, China began increasingly to coerce western firms that covet its massive market to transfer technology to their Chinese joint venture partners. But the problem for the rest of the world is that the Chinese market is opened selectively and in return for technology. That is how the unsustainable deficits pile up: for example, Indian pharmaceutical companies complain about the lack of access to the Chinese market when approximately 80% of the bulk drugs that they use to produce formulations and pills are imported from China.

Regional imperatives

China has frequently articulated its concern about the interdiction of its energy supplies, principally from the Gulf, through the Malacca Straits. It has undertaken numerous initiatives to overcome its “Malacca dilemma” through extensive port and pipeline building and these have been incorporated into the BRI.

In all, 64 countries are partners in the BRI, 57 of which participated in the Belt and Road Forum, held in Beijing on 14-15 May 2017. Of the 36 countries located in the IOR, 15 are among the designated partners and were represented at a high level. Of the remaining IOR countries, all except India and Oman, participated.

China has constructed pipelines, road and rail links in Russia and the Central Asian energy-rich countries to facilitate trade in energy and goods.

To India’s west, China plans to invest upwards of $60 billion in the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) which is the heart of the BRI, providing access to the Indian Ocean at Gwadar port. The corridor, passing through Indian territory in Pakistan- occupied Kashmir (PoK), is envisaged to dot Pakistan with power plants along upgraded rail and road connections from Gwadar to Xinjiang.

To India’s east, China has built a port in Kyakhpyu (Myanmar) to transport gas from the Gulf, and developed oil and gas pipelines to move Myanmar’s own gas, and imported oil and gas through Myanmar to its Yunnan province, circumventing the Malacca Straits. (India had hoped to import some of this gas from Sittwe port, but its Kaladan project is still incomplete.)

Also to our east, China, which is already building roads, rail lines and power projects in Bangladesh, is seeking association with port building and upgradation.

To our south, in Sri Lanka, China has built the Hambantota port and is constructing a new city near Colombo port, which handles approximately 75% of the transhipment of India’s trade.

Are Indian and Chinese imperatives incompatible?

India and China have collaborated to challenge the extant global governance paradigm. They worked together at global forums on issues, such as trade and climate change and combating Somali piracy. India and China also conduct rudimentary joint military and naval exercises. Wittingly or unwittingly, India cooperated in the creation of financial institutions, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), and the BRICS bank, that China is now instrumentalising to finance its vision of the BRI, including in Pakistan.

As the world adjusts to China’s challenge to the U.S.-dominated global system, India is among those most affected, because of its geographical proximity to China and a long disputed border. Despite its potential to be a peer competitor India has fallen seriously behind in economic power: the Indian economy is only 20% the size of China’s, with correspondingly lower trade volumes, outward flows of investment, and defence outlays.

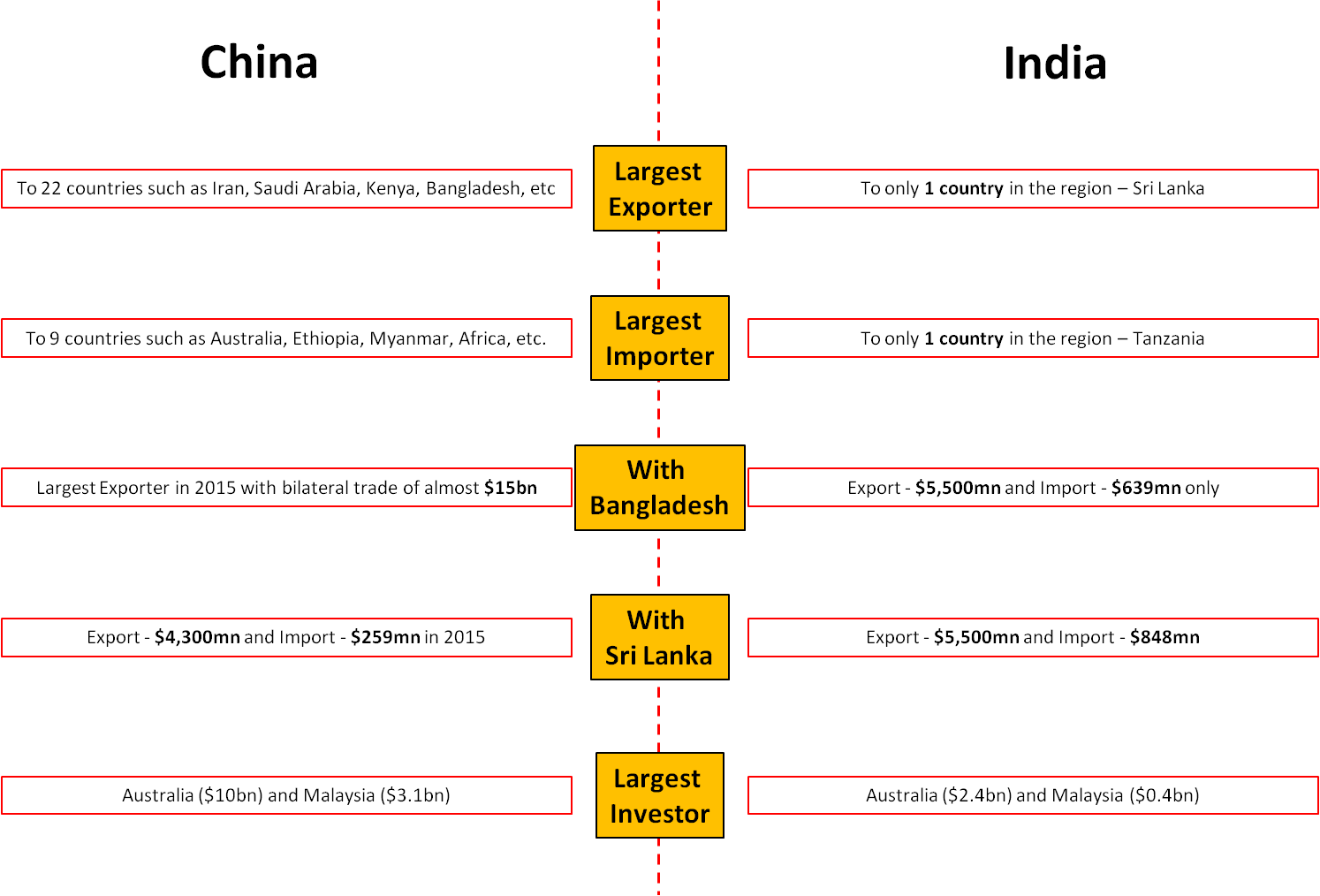

India’s influence even within the IOR has shrunk despite its advantages of location astride the Indian Ocean and historical links in East and South Africa, the Gulf, and South East Asia. But the greatest strategic erosion has been in relations with its South Asian neighbours. A quick India-China overview in the table below shows why:

China’s largest investments (excluding the CPEC in Pakistan) are in three IOR countries: Australia ($10 billion), Malaysia ($3.1 billion) and Singapore ($1.1 billion). In contrast, India’s investments in these countries are a fraction of these amounts: Australia ($2.4 billion), Malaysia ($0.4 billion), and Singapore ($5.9 billion).

The economic fortunes of these countries, or at least of the ruling elite in these countries, depend on the health of the Chinese economy and the goodwill of their rulers. China has often used trade as a weapon in political disputes such as stopping salmon imports from Norway after it awarded the Nobel Prize to Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo in 2010, cutting off the supply of rare earths to Japan the same year, halting tourism to, and banana imports from, the Philippines in 2012; and sanctioning South Korean companies and tourism for accepting the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) in 2016.

Naturally, there is an overlap between China’s global imperatives and those it has in the IOR. The first includes: the need for export markets and sources of raw material supplies, but most importantly, energy from the Gulf and gas from Myanmar. The second, an objective specific to the IOR, is: access to the ocean for its landlocked, underdeveloped regions, such as Yunnan, through Myanmar to India’s east, and Xinjiang through Pakistan to India’s northwest.

South China Sea disputes

China’s attempt at appropriation of nearly the entire South China Sea also has much to do with its quest for fishing and fossil wealth. Through its so-called “nine dash line”, China has, on dubious historical basis, claimed entire island chains, contravening the claims of Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei, Indonesia and the Philippines.

After rubbishing the 2016 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) tribunal’s award in favour of the Philippines’ ownership of Scarborough Shoal, China has managed to split the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN). Through a combination of military threats and financial largesse, it has forced claimant countries, including the Philippines, to agree to bilateral, rather than ASEAN-wide negotiations. China has rejected Japanese claims over the Senkaku island chain and criticised American freedom of navigation operations (UNOPS) in the disputed sea.

China is also pursuing sea bed mining for minerals and fossil fuels in the Arabian Sea, having already obtained a license to explore as far afield as the vicinity of Madagascar.

Territorial claims and resource hunts apart, China is also in need of friends in the neighbourhood to constrain the Uyghur separatists in the Xinjiang autonomous region. The rebellious Uyghurs are known to have received training in Pakistan and some amount of safe haven in Thailand.

Concerned about terrorist activities, China has offered to play a mediatory role in Afghanistan where it has invested billions in copper mining. It has similarly offered to mediate the sectarian differences in the Gulf. Both Saudi Arabia and Iran fit into its vision of the BRI, augmenting its access to the leadership. It already has an open door with Iran, given its part in the Iran-P5+Germany nuclear agreement. It is, moreover, the largest buyer of oil from both Iran and Saudi Arabia, displacing the U.S. as the largest buyer of oil globally (China imported $116.2 billion worth of crude oil in 2016, 17.3% of the world’s total crude oil imports).

China in the IOR

Another way to identify Chinese imperatives is to look at the IOR by region. While all the countries in the IOR are important markets for China, its other interests in the Gulf and East Africa pertain to energy and raw material imports. China now has a naval base in Djibouti and some facilities in Seychelles and Mauritius. It is deeply involved in infrastructure building in Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania and South Africa.

In South East Asia, China imports gas via, and from, Myanmar. It is the largest trader and investor in minerals and hydro power in that country. It is also a major investor in manufacturing and infrastructure as well as arms supplier in other ASEAN countries in the IOR, despite the conflicting territorial claims in the South China Sea.

While Vietnam remains publicly opposed to China’s insistence on bilateral negotiations, the Philippines has caved in with offers of $24 billion in investment in infrastructure, despite having won a favourable judgment from the UNCLOS tribunal. The Chinese diaspora is a significant player in ASEAN and was among early investors in China.

Even Vietnam, with its long history of resistance to China is vulnerable to economic pressure. China has invested $4.15 billion (between 2015 and 2016) in Vietnam and imported $25 billion worth of goods from it, and exported $66 billion (in 2015) to it. By comparison, India has investments worth $1 billion, and two-way trade of approximately $8 billion the same year.

The Chinese diaspora in Australia is of more recent origin – and perhaps closer to the Communist Party of China (CPC) than the Australians would prefer. It now numbers 1.2 million and constitutes 5.6% of the population. By comparison, the Indian Diaspora in Australia accounts for 2% of the total population, with approximately 460,000 Indians (by ancestry). Although Australia depends for its own high rates of growth on mineral exports to China, it has become increasingly uneasy and vocal in its allegations of efforts by Chinese firms to buy hi-technology companies.

South Asia

But it is Chinese activities in South Asia that are of the greatest concern to India, at least partly because, here, there is no separation between the geoeconomics and the geopolitics involved. All the South Asian countries, except Bhutan and India, are partner countries in the BRI and attended the BRI Forum at high levels.

CPEC, for example, is a threat to India for multiple reasons. The corridor, passing through PoK, implies that China no longer treats it as disputed territory. The stationing of Chinese troops in the region to protect its investments and personnel is a threat to India. The use of Karachi and Gwadar ports for submarines and warships is another red flag. Despite the U.S. finally taking the terrorist threat emanating from Pakistan seriously, Chinese financial support and diplomatic cover have emboldened Pakistan to step up support of activities inimical to India’s interests.

The infrastructure projects that China has built in Sri Lanka, including Hambantota port and the new port city near Colombo port too. are a concern. The latest deal between the Chinese and Sri Lankans on Hambantota is not reassuring either—despite claims that decisions regarding any military use of the port remains with the Sri Lankan government. On the positive side, Hambantota Port will be the poster child for warning small countries about falling into a Chinese debt trap and losing autonomy.

China is seeking to be associated with port building in Bangladesh too with sad implications for the continued stability of the Bay of Bengal. China is today the largest supplier of arms to Bangladesh, including a couple of submarines.

In the Maldives, China is modernising the airport (after displacing Indian company, GMR), building a link to the capital, Male, and has acquired an island on a 50-year lease supposedly to build a tourist resort. Its support has also stymied Indian efforts to deal with the dictatorial, Islamist regime that has emerged in the Maldives.

- The challenge from China has compelled India to expand its own activities and influence with the countries of the IOR. India has articulated this intent by converting its ‘Look East’ policy into ‘Act East’ vis-a-vis South East Asia. It has focused on the Security and Growth for All in the Region (SAGAR) strategy towards the western Indian Ocean countries and accorded heightened attention to the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC).

- India has also upgraded strategic relations with Japan and Australia, and drawn increasingly closer to the U.S., as expressed in the U.S.-India Joint Vision Statement for the Indo-Pacific, followed by the recent signing of the first of four foundational agreements, namely, the Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement (LEMOA). The creation of a countervailing coalition is helped along by the fact that although all the major countries in the IOR value China as an economic partner, they also want to hedge against its increasingly expansionist ambitions and mercantilist economic strategy. India is a welcome balancing factor.

Neelam Deo is Co-founder and Director, Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations, Mumbai and is a former Indian Ambassador.

This article has been adapted from a speech, titled, ‘China’s geoeconomic imperatives and their manifestation in the IOR’. It was delivered at a seminar on ‘An assessment of Chinese presence and initiatives in the IOR’, organised by the Western Naval Command, in Mumbai, on August 17.

You can read exclusive content from Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations, here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2017 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited