At the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) Summit in Kathmandu this week, connectivity was certainly on Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s agenda.[1] In fact, the issue of connectivity—ports, river channels, highways, railways, pipelines, and telecommunication cables—has gained global momentum this month. It was a major part of the discussions at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Summit in Beijing, as well as at the G20 Summit in Brisbane, both held earlier in November.

China has been at the forefront of the regional connectivity drive. It has been putting together finance mechanisms to keep routes viable, and upgrading its domestic infrastructure. In 2012, the country’s National Development and Reform Commission announced 45 infrastructure projects—including ports, river channels, highways, and railways.[2] More recently, in September, President Xi Jinping announced additions to existing regional infrastructure projects, including the second phase of the Hambantota Port Project, as part of China’s ambitious strategy to “break the bottleneck in Asian connectivity.”[3]

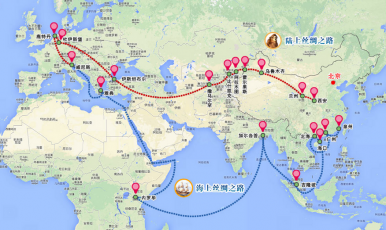

(image credit: Xinhua)

China’s regional connectivity drive is based on a three-pronged approach:

First, the routes. The New Silk Road could eventually connect China to western Europe via Central Asia. The Maritime Silk Route (from Fuzhou on China’s eastern seaboard to Venice, via the Indian Ocean) will connect ports in Sri Lanka and Pakistan, which are being developed by China.

The proposed Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar (BCIM) corridor that will physically connect the four countries, and the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor Flagship Project,[4] announced at the APEC summit, will allow China access to the Arabian Sea and form a huge network in the next 10 years with China at the centre.

The second aspect of this strategy is the instruments through which China aims to finance these plans. At the APEC Summit, Xi announced a $40 billion[5] Silk Road Infrastructure Fund, which is part of the $1.25 trillion in outbound foreign direct investment announced by Xi before the summit.[6] Add to this, the two recently-announced multilateral lending banks—the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the BRICS New Development Bank, with initial capital of $50 billion[7] and $100 billion[8] respectively.

The third facet of the Chinese connectivity strategy is making these physical routes viable by expanding the volume of trade along these routes through trade agreements. At the APEC Summit, China actively pushed the Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP)[9] among APEC countries. The FTAAP is not a new idea, but with Beijing now driving the discussion, it is likely to be accelerated after the endorsement by APEC leaders of the “Beijing Roadmap for APEC’s Contribution to the Realization of the FTAAP”.

It looks increasingly likely that the under-discussion Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership—that includes India, along with the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN), Australia, China, New Zealand, South Korea, and Japan—will be sidelined in favour of the FTAAP and the Transpacific Partnership (TPP). India could be left behind in global trade since it is not part of either the FTAAP or the U.S.-led TPP—the two largest plurilateral free trade agreements.

A huge deficit already exists between China’s and India’s internal and external connectivity—for example, India has added 15,000 kilometres of railway track since 1947, while China has increased its railway track by nearly four times in the same period, 18,000 kilometres of this consisting of high-speed rail (the world’s largest).[10]

The expansion of India’s connectivity is hindered by four major factors: an aversion to an infrastructure build-out in the Northeast, tardy policy reform, the country’s corruption-ridden implementation of projects, and its reticent responses to China’s overtures.

India has historically viewed connectivity with China through a defensive lens. One of the aftereffects of the India-China war in 1962 has been the resistance of successive governments to an infrastructure build-out between the Northeast and the rest of India. The trust deficit with China has also compromised linkages and the creation of trade routes with Central Asia.

Industrial corridors are a priority for India, but as of now, only Japan is involved in these projects. Unfortunately, the $90 billion[11] Delhi Mumbai Industrial Corridor—financed by Japanese official development assistance (ODA) and envisioned as a template for internationally-funded industrial corridors in India—has suffered from resource and policy issues such as land acquisition reform and a complex tax structure. This may have deterred other countries from investing in India’s infrastructure.

New Delhi has declared that India suffers from a $1 trillion infrastructure deficit, and India (with foreign reserves worth $315 billion) cannot hope to match China’s (nearly $4 trillion) scale of infrastructure investment.[12] & [13] India will, for now, continue to rely on foreign investment and ODA to bankroll the construction of its internal infrastructure and regional connectivity. China has offered a $20 billion[14] investment in Indian infrastructure and SEZs, but the extent to which India will change its position on China remains to be seen.

As it stands, the sole China-related connectivity project in which India is involved is the BCIM—for which New Delhi announced its backing only this year. But it has not publically declared its support or participation in China’s proposed Maritime Silk Route.

However, this remains a propitious moment for India to expand its connectivity, because it is viewed in the region as a non-threatening power, as compared to the economically expanding and militarily threatening China, with which many ASEAN countries have territorial disputes.

Beijing, backed by its economic might and nodal role in global supply chains, is now moving to expand relations with Hanoi, despite its territorial disputes with Vietnam. New Delhi should grab this limited window of opportunity, particularly if China reaches out to the other countries with which it has disputes, sheds its current expansionist policy of indisputable claims, and in the process is no longer perceived as a regional threat.

But if India drags its feet on boosting its linkages with regional partners, China—already a major part of most global value chains—could become as irreplaceable to ASEAN as the U.S. is to trade with European countries

In order to push India’s connectivity agenda, Modi must follow up on his meetings at the SAARC Summit this week. Besides taking forward discussions on the construction of the BCIM with Bangladesh, it is crucial for India to keep making progress on the proposed agreements with SAARC members—already cleared by the Indian government—on rail and road connectivity, and the setting up a SAARC Special Purpose Facility[15] to finance these projects.

Karan Pradhan is a Senior Researcher at Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations.

Dev Lewis is Outreach Associate at Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2014 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited

References:

[1] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, Media Briefing, 23 November 2014, < http://www.mea.gov.in/media-briefings.htm?dtl/24311/Transcript_of_Media_Briefing_by_Official_Spokesperson_and

_Joint_Secretary_North_on_Prime_Ministers_forthcoming_visit_to_Nepal_

November_23_2014>

[2] Ip, Stephen, and Peter Fung, Infrastructure in China, KPMG, 15 June 2013. < http://www.kpmg.com/CN/en/IssuesAndInsights/ArticlesPublications/documents

/Infrastructure-in-China-201302.pdf>

[3] Xinhua, APEC Members Agree on Connectivity Blueprint, 11 November 2014, < http://news.xinhuanet.com/english

/china/2014-11/11/c_133782132.htm>

[4] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, People’s Republic of China, Li Keqiang: Building the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor Flagship Project, 8 November, 2014, <http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/topics_665678/ytjhzzdrsrcldrfzshyjxghd

[5] Xinhua, China Pledges 40 Bln USD for Silk Road Fund, 8 November 2014, <http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2014-11/08/c_133774993.htm>

[6] Bloomberg, Xi Dangles $1.25 Trillion as China Counters U.S. ‘Pivot’ to Asia, 9 November 2014, <http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-11-09/president-xi-says-7-percent-gdp-growth-makes-china-top-performer.html>

[7] Xinhua, 21 Asian Countries Sign MOU on Establishing Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, 24 October 2014, < http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/business/2014-10/24/c_133740149.htm>

[8] BRICS, VI Summit, Agreement on the New Development Bank – Fortaleza, 20 July, 2014, < http://brics6.itamaraty.gov.br/media2/press-releases/219-agreement-on-the-new-development-bank-fortaleza-july-15>

[9] APEC, 2014 Leaders’ Declaration, 11 November 2014, <http://www.apec.org/Meeting-Papers/Leaders-Declarations/2014/2014_aelm.aspx>

[10] Singh, Sarwant, ‘A Closer Look at the Chinese High Speed Rail Juggernaut: The Chinese Closer to Elon Musk’s Hyperloop than the US (Part 2), Forbes, 4 August, 2014, < http://www.forbes.com/sites/sarwantsingh/2014/08/04/a-closer-look-at-the-chinese-high-speed-rail-juggernaut-the-chinese-closer-to-elon-musks-hyperloop-than-the-us-part-2/>

[11] Delhi Mumbai Industrial Corridor, Introduction, <http://delhimumbaiindustrialcorridor.com/introduction.html>

[12] Reserve Bank of India, Weekly Statistical Supplement, 11 July, 2014, <http://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/WSSView.aspx?Id=19419>

[13] State Administration of Foreign Exchange, People’s Republic of China, The time-series data of China’s Foreign Exchange Reserves, 20 October 2014, <http://www.safe.gov.cn/wps/portal/english/Data>

[14] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, India-China Joint Statement, 1 January 2014, <http://www.mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/24022/Joint_Statement_between_the_Republic_of_India_and_

the_Peoples_Republic_of_China_on_Building_a_Closer_Developmental_Partnership>

[15] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, Prime Minister’s speech at the 18th SAARC Summit, 26 November, 2014, <http://www.mea.gov.in/Speeches-Statements.htm?dtl/24321/Prime_Ministers_speech_at_the_18th_SAARC_Summit>