In October 2020, with the world writhing under the pain of COVID-19, the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) held triennial elections to select 15 new members.[1] Despite its abysmal human rights record, and the human and economic devastation inflicted by COVID globally, China was elected as a member — with the lowest number of votes.[2] Now here it stands, with a sheen of credibility provided by the UN.

Then, on May 4, China was further embedded into the U.N. system. China’s Vice Minister in the Ministry of Commerce, Xiangchen Zhang, was appointed as one of four new Deputy Directors-General of the World Trade Organization (WTO) along with the U.S., France, and Costa Rica. India’s candidate lost.[3]

China’s ascendancy in the U.N. seems almost unquestioned. Is it unexpected?

Not really. Gateway House has traced China’s expanding influence in the United Nations, its related bodies, and influential non-UN multilateral bodies. The research was conducted over four months in 2020-21, studying the most important multilateral agencies in the world including UN agencies, funds and programmes, as well as non-UN security, finance, and scientific agencies.

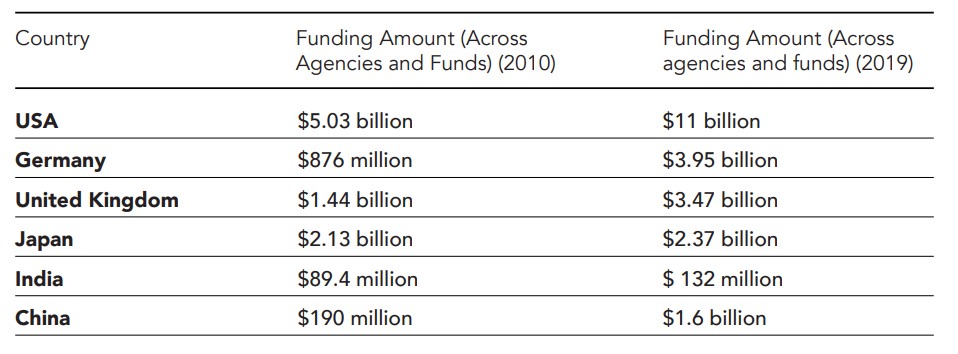

The findings revealed that China is in a dominant position in several critical multilateral bodies, in both personnel and funding. The most prominent are the International Telecommunications Union (ITU), the United Nations Industrial Development Organisation (UNIDO), the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO), the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), and the International Maritime Organisation (IMO).

The links are obvious. ITU sets global telecommunications standards – where China’s Huawei is a major player. UNIDO was formed to encourage industrialisation in the developing world but its importance has waned as countries found it unhelpful, leaving China in charge. China immediately connected UNIDO to its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which UNIDO now endorses. China’s positioning at ICAO, which sets air navigation and safety standards, ensured that during the pandemic, Taiwan was excluded from all discussions – just as it was with the World Health Organization (WHO), over which China has a disproportionate influence.[4]

How did this happen?

While the world was preoccupied with opening the Chinese internal market, China spent years preparing to dominate and leave its mark on the external global system.

In fact, it has been part of China’s global agenda since 1992. By 1997, China was a member of 20% of multilateral organisations, up from 12% in 1989, and by 2002, started to create new ones, like the Shanghai Cooperation Organization.[5] Over the last two decades, ever since it entered the WTO in 2001, China has set out to influence the global multilateral system.

The participation has grown more sophisticated over the years. China has carefully chosen clusters of agencies to lead, whose work can be interwoven with and are interlinked to its own domestic agendas like ‘Made in China 2025’, and the rise of Chinese companies. The multilateral agenda includes creating new global standards for technology, which can be led by China and its national corporate champions. These in turn, are linked to China’s foreign policy strategy led by the Belt and Road Initiative, which has its own expansion plans – the Digital Silk Road, Space Silk Road, and the Health Silk Road.

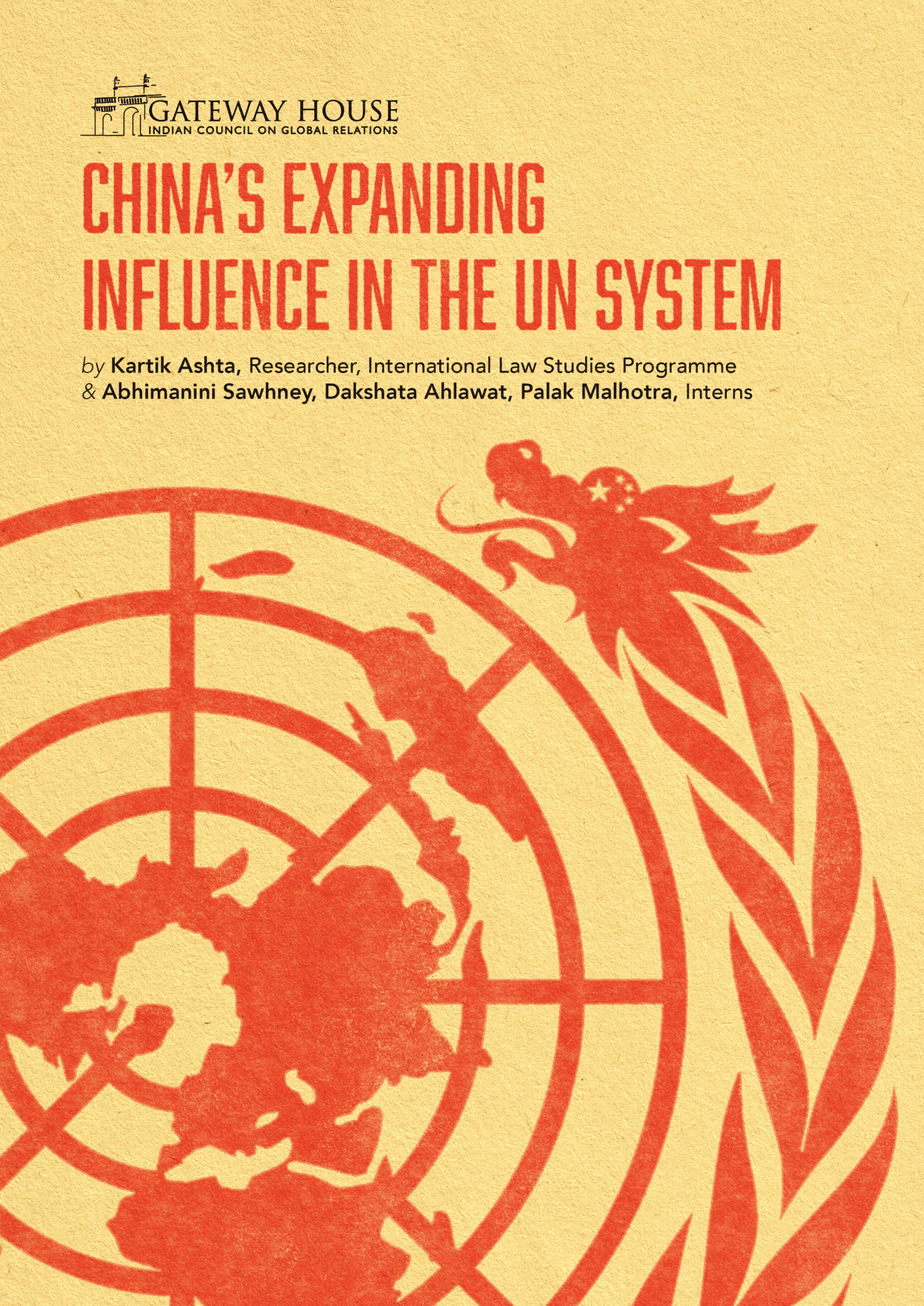

The expanding influence is enabled by China’s increased monetary contribution to the UN, both mandatory as a UN member, and increasingly, voluntary donations. According to this study, these have risen by 1096% and 346% respectively from 2010 to 2019.[6]

Source: UN System Chief Executives Board for Coordination

China’s influence-seeking has serious implications for global development, global rules and regulations, standards — both digital and scientific, and multilateralism.

This research highlights the connections.

1. China is present either as the head or a deputy position in almost all the critical international agencies.

- China directly heads four of the 15 principal agencies of the UN – FAO, UNIDO, ITU, ICAO.

- Chinese deputies are present in 9 of the 15 agencies – World Bank, International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), International Monetary Fund (IMF), IMO, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), WHO, World Meteorological Organization (WMO).

- China influences UN agencies through its proxies. The current Director General of the WHO, Tedros Adhenoum Ghebreysus was elected with China’s support in 2017.[7] He is the former health and foreign minister of Ethiopia, which is one of the largest recipients of Chinese investments in Africa.[8] The WHO was previously headed for 10 years by Margaret Chan, from Hong Kong.[9] The WHO’s delayed warnings and travel restrictions regarding the pandemic in China, is a globally devastating outcome borne of China’s influence.

- Liu Zhenmin, a lawyer with China’s foreign ministry, heads the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA).[10] Popularly considered the UN’s think tank, DESA writes papers, publishes reports, and convenes conferences.[11] Zhenmin was appointed by Secretary General Antonio Guterres in 2017, but China has held this position since 2007 when Sha Zukang, a career diplomat, was first handed the post by Ban Ki-moon, the previous Secretary General. DESA is populated by several Chinese nationals.[12]

- China also has a network of its nationals, who are career professionals or diplomats, at the lower rungs of the UN system. These officers, who have entered the UN system laterally, or through the Junior Professional Officer (JPO) programme, are supposed to be impartial but may not be.[13]

2. Some agencies are still firmly in the grip of the Western powers. For instance, the World Bank is with the U.S., the IMF is with the EU, the Office for the Co-ordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) is with the U.K., and the Department of Peacekeeping Operations is with France. China has been rising here too – it has its people in senior positions at financial institutions, eg: Shaolin Yang at the World Bank and Tao Zhang at the IMF.[14]

3. In institutions where China occupies no position, such as the International Labour Organization (ILO), Universal Postal Union (UPU), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and UN Habitat, it has signed Memorandums of Understanding between those UN agencies and its Belt and Road Initiative through relevant domestic ministries, often leveraging its capacity for voluntary funding. Thus, in effect, China’s foreign policy agenda gets endorsed and co-promoted by the UN. [15]

For instance, Fang Liu, the Director General of the ICAO, signed a new economic and technical cooperation agreement with the Vice Minister of Commerce of China, through which the Government of China pledged to provide ICAO with a grant of $4 million for projects to improve operational safety, aviation security and sustainable development of air transport.[16] The agreement neatly ties in with Chinese objective of boosting interconnectivity and infrastructure development via the Belt and Road initiative.

This is not unique to China. Major powers practice this as well through private NGOs and official development agencies. What is new is China’s increasing role in the multilateral structure and the simultaneously reduced position of other countries.

4. Several agencies, such as the International Telecom Union (ITU), have Chinese representatives serving two terms. This ensures that Chinese national champions like Huawei and its standards become embedded and implemented by UN agencies engaged in development work in sparsely penetrated markets like the African continent, the Pacific, and South and Southeast Asia. An example of this is the acceptance of blockchain standards for finance proposed at the ITU by the People’s Bank of China, the China Academy of Information and Communications Technology, and Huawei.[17] Again, this is not new, as Western nations have imposed their own standards for years. But it does show that China is trying to supplant them as the standard setter of the world.

5. On funding, China has learned from its predecessors. The membership-based multilaterals have two types of funding: “assessed” or mandatory, a formula-based amount depending on a number of factors including a country’s GDP and financial capacity; and voluntary, which includes countries donating directly to the UN, its agencies and funds and programmes, or non-government organisations supporting programmes that align with their goals. For instance, the Ford Foundation and Rockefeller Foundations have been mainstays in voluntary contributions to UN Women, UNDP, and the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). In 2018, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation became the 17th largest funder to the top UN bodies.[18]

China is catching up. In mandatory contributions, at 12% of the total, China is the second largest donor. Its voluntary donations have also been increasing, from $51 million in 2010 to $172 million in 2019, a 346% rise in nine years. Combined, China becomes the fifth largest donor to the UN. This has implications. The study shows that where China is not leading an organisation, it almost certainly makes voluntary contributions. The voluntary contributions enable the UN’s funds and programmes agencies to run their special projects, as only administrative, daily expenses are covered by the UN’s core budget. So, when China makes a $7.5 million contribution to the UNDP, it can influence the way development projects are implemented.

China is increasingly involved with the UN’s Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPO) through a recent $1 billion pledge to the UN Peace and Development Fund – as the largest donor. This is viewed by some as a way for China to keep an eye on its investments in Africa.[19]

6. Finally, even if Chinese nationals, its government or its ministries are not prominent in the UN, its state-owned companies The International Seabed Authority, which is “mandated under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea to organise, regulate and control all mineral-related activities in the international seabed area for the benefit of mankind as a whole” has awarded five contracts to Chinese companies for deep sea mining of polymetallic nodules, sulphides, and cobalt rich ferromanganese crusts. [20]

In the next two years, some critical appointments will be made. The ICAO will have a new Secretary General in September 2021,[21] and the heads of the UNIDO and ITU will complete their terms in 2021 and 2022 respectively. That leaves China leading just one principal agency, the FAO, for which a new Director General will be elected in 2023.

By then, China will have achieved its immediate goal i.e., to influence principal multilateral bodies, and will move to its next: leading the institutions that oversee soft power – heritage, trade and commerce like UNESCO, UNCTAD, and UPU which have elections this year. At UNESCO, nominations have been filed and the incumbent, Audrey Azoulay of France, is unopposed.

The critical election is that of the Universal Postal Union (UPU), which influences global e-commerce. In 2019, the U.S. renegotiated the Postal Treaty increasing stamp costs on post and mail which originated from China, impacting Chinese e-commerce sales the world over. With China already the world’s largest e-commerce player, and with the Chinese Communist Party now in virtual control of Alibaba, its e-commerce giant, the stakes for China’s global commercial dominance are higher than ever.

Where does India stand in all this, and what can it do? Some recommendations are below:

1. India must aim to be a proactive rule maker and not the defensive rule taker it has been so far. It is, therefore, important that it embeds itself in the multilateral system. One way is to set up and lead its own multilaterals, as it has already done with the International Solar Alliance and Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure. India tried to lead with the BRICS-promoted New Development Bank, but it is playing second fiddle to China there and at the dynamic Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank, where China is the promoter and largest shareholder, followed by India which has an 8% shareholding.

2. Increase funding. India can increase its voluntary contributions to agencies, funds, and bodies where it believes it can play a more conducive role. Indian philanthropy, quiet but growing, can also be directed to these agencies. For instance, UNESCO, is looking for funds, and given India’s diverse history, heritage and culture, a closer engagement would be welcome. Indian telecom and tech companies are emerging leaders in the world market, and a larger presence in the ITU would not go amiss as well.

India’s recent Permanent Representative to the UN, Syed Akbaruddin, suggested upping the contribution from $132 million to $700 million at least, closer to China’s $1.6 billion.[22] Then it can start to play a greater role in the UN Environment Programme, UNDP and UN Habitat, given its thrust on renewable energy, climate change and affordable housing.

3. Strategically place the right people in the system and align with like-minded partners. It is not always possible to get a national elected to the top job, given the influence of the P5 and other countries like Japan, South Korea, Brazil and Argentina, – which have been embedded in the system for years. However it is possible to get friendly candidates in through friends who can push the levers.

In its self-interest, India can and should sponsor its nationals for influential policy positions in the UN system, much like the Chinese have done with the DESA and the Junior Professional Officer Programme.[23] Signing on for these agencies and programmes will develop, for India, a cadre of career UN diplomats who will ensure that these critical bodies are not dominated by any country, so that they address global problems and issues in a balanced and impartial manner.

With appreciation to Ambassador Manjeev Puri, India’s Deputy Permanent Representative to the United Nations 2009-13, who was a guiding hand for this project.

This study was conducted by Gateway House’s 2020-21 Winter Interns Kartik Ashta, Abhimanini Sawhney, Dakshata Ahlawat and Palak Malhotra. Read the report.

This report was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the authors, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2021 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References:

[1] Election of the Human Rights Council, 13 October 2020, available at: https://www.un.org/en/ga/75/meetings/elections/hrc.shtml

[2] China Grudgingly Gets UN Rights Body Seat, Sophie Richardson, Human Rights Watch, October 13, 2020, available at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/10/13/china-grudgingly-gets-un-rights-body-seat

[3] DG Okonjo-Iweala announces her four Deputy Directors-General, 4 May, 2021, https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/news21_e/dgno_04may21_e.htm

[4] UN aviation agency blocks critics of Taiwan policy on Twitter, Bethany Allen-Ebrahimian, Axios, January 27, 2020, https://www.axios.com/as-virus-spreads-un-agency-blocks-critics-taiwan-policy-on-twitter-e8a8bce6-f31a-4f41-89e0-77d919109887.html

[5] Why Nations Rise: Narratives and the Path to Great Power, Manjari Chatterjee Miller, 152, Oxford University Press, 2021

[6] UN System Chief Executives Board for Co-ordination, https://unsceb.org/fs-revenue-government-donor

[7] China’s Influence over the UN, Neelam Deo, Gateway House, 7 May 2020, https://www.gatewayhouse.in/chinas-influence-un/

[8]The WHO and China: Dereliction of Duty, Michael Collins, Council on Foreign Relations, 27 February 2020, https://www.cfr.org/blog/who-and-china-dereliction-duty

[9] Former Director General: Dr Margaret Chan, available at: https://www.who.int/dg/chan/en/

[10] United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, https://www.un.org/development/desa/statements/usg-liu.html

[11] United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, available at: https://www.un.org/en/desa#:~:text=As%20the%20think%20tank%20of,options%20to%20tackle%20common%20problems.

[12] Former USGs, https://www.un.org/development/desa/statements/previous-usg.html

[13] How China Is Remaking the UN In Its Own Image, Tung Cheng-Chia and Alan H. Yang, The Diplomat, April 9, 2020, available at: https://thediplomat.com/2020/04/how-china-is-remaking-the-un-in-its-own-image/

[14] The World Bank Group, https://www.worldbank.org/en/about/people/s/shaolin-yang; International Monetary Fund, About, Tao Zhang, available at: https://www.imf.org/en/About/senior-officials/Bios/tao-zhang

[15]China Enlists UN to Promote its Belt and Road Project, Colum Lynch, Foreign Policy, 10 May 2018, available at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/05/10/china-enlists-u-n-to-promote-its-belt-and-road-project/; also see: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/26318/UN%2525252525252520Agencies%2525252525252520BRI%2525252525252520Involvement%252525252525252002%2525252525252520%252525252525252801%2525252525252520Oct%25252525252525202018%2525252525252529.pdf?sequence=17&isAllowed=y

[16] ICAO Secretary General highlights the role of aviation in the High Level Dialogue of the Belt and Road Forum in Beijing, 18 May, 2017, available at: https://www.icao.int/Newsroom/Pages/ES/ICAO-Secretary-General-highlights-the-role-of-aviation-at-High-level-Dialogue-of-the-Belt-and-Road-Forum-in-Beijing.aspx

[17] China sets global blockchain standards, Canaan is alive: Blockheads: Technode, 8 September 2020, available at: https://technode.com/2020/09/08/blockheads-china-sets-global-blockchain-standards-and-canaan-is-alive/?utm_source=TechNode+English&utm_campaign=947b98a299-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2020_06_03_04_13_COPY_01&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_c785f26769-947b98a299-111988938&mc_cid=947b98a299&mc_eid=978e88078f

[18]Who actually funds the UN and other Multinationals? John Macarthur and Krista Rasmussen, The Brookings Institution, 9 January 2018, available at: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2018/01/09/who-actually-funds-the-un-and-other-multilaterals/

[19] China’s pragmatic approach to UN peacekeeping, Richard Gowan, The Brookings Institution, 14 September 2020, available at: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/chinas-pragmatic-approach-to-un-peacekeeping/; China has also recently set up an overseas base in Djibouti.

[20] International Seabed Authority, Exploration Contracts, available at: https://www.isa.org.jm/exploration-contracts

[21] Juan Carlos Salazar of Colombia was elected in February 2021 and will take on his responsibilities in September.

[22] Tathya 2021 Conference, Opening Remarks by Ambassador Syed Akbaruddin, at: 1:12:54, available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lFLCdqcnxIU

[23] United Nations Junior Professional Officer Programme, available at: https://careers.un.org/lbw/home.aspx?viewtype=AEP&lang=en-US