Introduction

In 2015, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) announced the most extensive set of reforms for the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) in its history. These reforms sought to consolidate President Xi Jinping’s hold over the Army and bring about jointness in the forces by replacing military regions with theatre commands. They also focused on moving the PLA from legacy military capabilities by creating two new services – Joint Logistics Support Force (JLSF) and Strategic Support Force (SSF). These reforms come on the back of China’s military spending, which has surpassed the annual GDP growth, reflecting Beijing’s priority to military modernisation and the growing role of the military in its global ambitions.

The reforms have far-reaching implications for India and the region because they are turning the PLA from a bloated and corrupt military to a capable force.[1] They signal a significant expansion of Beijing’s conventional military power and space and offensive cyber capabilities. China is now amplifying its focus on maritime, cyber and tech-based threat perception.

China’s increasingly assertive posture vis-à-vis its neighbours and the U.S. in recent years, demonstrates its confidence in military capabilities. From Ladakh to the Taiwan Straits, belligerent Chinese behaviour is on display. Therefore, it necessitates understanding the nature of the reforms and the structural changes initiated within the PLA.

This paper discusses the reforms and examines their implications for regional security, with a focus on India.

Methodology

For research on this subject, official sources (the PLA documents and Chinese Ministry of National Defense) in English and Mandarin have been used. Translation of the PLA’s flagship doctrinal document, Science of Military Strategy, 2013, is publicly available from the Air University of the United States, and American strategic analysts’ works on the PLA are cited. The Chinese analysts’ commentary available on the China National Knowledge Infrastructure portal was translated and used for this research. The author also interviewed Indian strategic experts who study the PLA’s military capabilities and Party-Army ties. A list of these experts is available at the end of this document.

Background

The birth of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949 was a result of a political revolution achieved by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). The military’s significance for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s consolidation is often underlined by PRC founder Mao Zedong’s slogan given in 1927, “Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun.”[2] Moreover, the CCP has often claimed that it represents Chinese people’s interests. Therefore, the party has contended that having the PLA serving the party is “tantamount to serving the state and the Chinese people.”[3]

A formal arrangement consolidated this symbiotic Party-Army relationship after the establishment of the PRC. Under this arrangement, Chairman, CCP, was also made Chairman, Central Military Commission (CMC)—the highest decision-making body on military affairs. Seven decades since the PRC’s establishment, the CCP has relied on the PLA for unifying and governing the country, demonstrating the criticality of the PLA.[4] Its significant role in ensuring order was evident during the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s and the Tiananmen Square Crisis of 1989.[5]

Conceived mainly as a ground force, the PLA has expanded and modernised significantly over the years.[6] Under the chairmanship of Xi Jinping, the PLA is aspiring to become a “world-class” military by 2049 and emerge as a force steeped in the CCP ideology.[7] As the 18th Party Congress Work Report of November 2012 noted, “To modernise national defense and the armed forces, we must follow the guidance of Mao Zedong’s military thinking, Deng Xiaoping’s thinking on enhancing our military capabilities in the new historical period, Jiang Zemin’s thinking on strengthening our national defense and armed forces, and the Party’s thinking on strengthening our national defense and armed forces under new conditions.”[8]

As part of this, the CCP undertook a series of detailed reforms of the PLA starting 2015. The aim in PLA’s own words was to break down “systematic, structural, and policy barriers,” modernise “the organisation of the military,” and improve “combat capacity.”[9]

Rationale for PLA’s extensive reforms

The PLA—the world’s largest military force with more than 2 million active personnel—is often described as “party-army with professional characteristics”. However, Mao’s successor, Deng Xiaoping, made a concerted effort to put the PLA under the command of the state instead of the CCP—an initiative carried forward by his successors, albeit with varying degrees of emphasis.[10] The ascent of Xi Jinping in 2013 marked a new chapter as he sought to inject a renewed sense of party ideology into the PLA and modernise it.

Taking forward Xi’s initiative, in November 2015, the party announced a series of detailed reforms for the PLA. According to the CMC, the objective was to “consolidate and improve the fundamental principles and systems of the party’s absolute leadership” over the PLA, and reinforcing their symbiotic relationship.[11] As noted earlier, these reforms had been on the CCP agenda since the 18th National Congress. While the PLA had implemented reforms earlier too, the current reforms are far more sweeping than the previous ones, given the dismantling of the existing structures and creating new forces. This was the first time that the CMC identified definite time-frames for these reforms: “integrated” by 2020, “informationised” by 2035, and “world-class” by 2049.[12] Though “world-class” is not explicitly defined, a rough survey of PLA Daily suggests that world-class forces are roughly similar to major military powers, including the U.S., France, UK, and to a certain extent in some elements India.[13] This points towards the ability to deploy (including airlift) troops with agility and flexibility anywhere, including abroad, to protect the Chinese interests. [14]

The reforms align with China’s expanding overseas footprint—investments under the Belt and Road Initiative, growing profile of the PLA Navy (PLAN) in anti-piracy operations and its first overseas military base in Djibouti, in the Horn of Africa. It puts the PLA on a par with the major militaries of the world in terms of force posture and joint capabilities.[15]

The Science of Military Strategy of 2013 had articulated the underlying thought behind these reforms. According to it, China’s strategic tixi (system of systems) should be constituted from the three levels and five types of strategy: national strategy—military strategy— the services’ strategy, the theatre of war strategy, and strategies for the major security domains (nuclear, outer space, and cyber spaces).[16]

According to Chinese scholar Yan Hui, reforming the PLA is necessary as the PLA faced several problems like excessive scale, single arms, unsound institutions, inconsistent organization, and irregular military management.”[17] Consequently, according to him, China lagged behind other militaries in terms of modernisation. One analyst Dang Yifei has described these reforms as a combination of “political sobriety” and “strategic determination” to achieve combat effectiveness.[18] Another analyst Dai Kun has noted that these reforms have a “high degree of responsibility,” “a scientific reform strategy,” and “a strong appeal to the times” to ensure PLA’s transformation in a world class military.[19]

Xi has often cited the PLA reforms as a means to crack down on the corruption within the military, similar to the initiative that he had launched for the CPC.[20] According to Xinhua, since the 18th National Congress in 2012, more than 100 PLA officers at or above the corps level, including two former CMC vice chairmen—General Guo Boxiong and General Xu Caihou—have been punished during the anti-corruption drive by being given life sentences, dismissal from the service and expulsion from the CCP.[21] However, outside China, Indian and Western experts have largely perceived this crackdown as also being aimed at purging the political opponents of Xi, thereby helping him to strengthen his grip over the party and the army.[22]

The restructuring of the PLA comes on the back of an exponential increase in China’s defence budget since the late 1990s.[23] For the past decade, its military spending has surpassed the annual GDP growth, reflecting Beijing’s priority to military modernisation and its global ambitions. In 2020, its spending was $209.16 billion (1.268 trillion yuan). According to the Chinese Ministry of Finance figures, this year, spending is expected to be close to $208 billion (1.35 trillion yuan). [24]

There is little transparency on China’s actual defence expenditure, but one trend that has become clear since 2010 is that China’s internal security spending has exceeded the external defence spending, and the gap between the two is expanding with increased security expenditures to maintain stability and order in Tibet and Xinjiang provinces.[25] In 2017, China’s internal security spending was equivalent to about $349 billion—compared to the official external defence spending of $150 billion.[26][27]

The following section identifies four dimensions of the PLA reforms: reorganisation of the CMC, introducing the theatre commands, troops’ demobilisation, and creation of new forces.

Overview of reforms

1.Consolidating Xi’s control over the military through reorganisation of the CMC

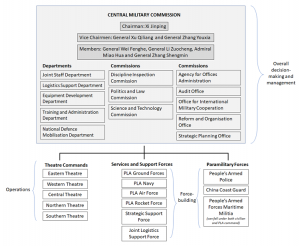

The most important initiative as part of these reforms was the reorganisation of the seven-member CMC, which is responsible for the overall management of the PLA (see figure 1). The CMC is both a state institution and a CPC organ. But the CPC holds de facto control over it, as the General Secretary of the CPC is also the Chairman of the CMC, i.e., Xi. Currently, other six members of the CMC are Vice Chairmen General Xu Qiliang (from PLA Air Force [PLAAF]) and General Zhang Youxia (PLA), General Wei Fenghe (Defence Minister), General Li Zuocheng (Chief of the Joint Staff Department), Admiral Miao Hua (PLAN) and General Zhang Shengmin (PLA Rocket Force).[28]

In January 2016, the CMC’s four general departments—staff, politics, logistics, and armaments—were reorganised into 15 “functional segments, including seven departments, three commissions, and five directly affiliated bodies.”[29] The CCP deemed the earlier four general departments as representing the Soviet-style top-down chain of command and highly bureaucratic decision-making. In its place, the reorganised CMC streamlined the command by giving it to the respective agencies, while retaining the final decision-making authority with Chairman, CMC.[30] The new agencies included the general office, joint staff, political work, logistical support, equipment development, training and administration, and national defence mobilisation. Chinese sources describe the reorganised CMC as doing overall decision-making and management, while theatre commands focus on operations, and the forces (existing and newly created).[31]

Figure 1: Chinese military structure

Source: Office of the Secretary of Defense, Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2018 (Washington, D.C., 2018), p. 4; Gateway House

2. Moving towards jointness with the theatre commands

According to the Science of Military Strategy of 2013, before introducing jointness, the PLA operated in silos and was attuned towards previous-generation mechanised warfare age. Therefore, the document Strategy recommended the re-orientation of the PLA towards “integrated joint operations under informatised conditions.”[32]

Indian and Western strategic experts argue that the PLA has studied the U.S. military campaigns in Kosovo (1999), Iraq (2002), and Afghanistan (2001),[33] learned from them, and absorbed it into their own system. For instance, the demonstration of the American military in joint fighting, new technologies, rapid troop deployment capability across theatres and out-of-area operations convinced the CPC and the PLA to put in place its plans for joint war-fighting – the PLA generals use the term ‘integrated joint command’ – in case hostilities break out with against the U.S. and neighbours like Japan, Taiwan and India.[34]

In February 2016, the PLA introduced five theatre commands responsible for territorial defence of the North, South, East, West, and Central regions (see figure 2).[35] These commands differ from the U.S. military, whose combatant commands span the globe. The new PLA commands replaced the seven military regions—a concept dating back to the 1950s (though their numbers changed throughout the history, as per the reorganisation of the regions), in which they had become too ground force-focused.[36] The difference between the military regions and the theatre commands is that the former were more administrative, while the latter focused on combat operations.[37] The theatre commands report directly to the CMC and combined command of various forces, including the PLA ground force, PLAN and PLAAF. The theatre commands fight together under informationised conditions to achieve a specific objective or “strategic direction”, for instance, the reunification of Taiwan.[38]

The new theatre commands represent external orientation as these commands are primarily structured based on threat perceptions facing the specific Chinese border.[39] For instance, the Western Theatre Command, the largest command, directly faces India, focusing on the contentious Line of Actual Control (LAC). It also oversees the Xinjiang and Tibet autonomous regions. Similarly, the Southern Theatre Command is focused on the South China Sea, where China has an ongoing maritime dispute with Vietnam, Taiwan, the Philippines, Brunei, Indonesia, and Malaysia.

Figure 2: China’s theatre commands

Source: Gateway House Research (Map only for representational purposes)

Pertinently, these theatre commands aimed to integrate command of various forces, reduce the elite stature of the PLA ground forces officers and strengthen the PLAN and PLAAF. But Indian strategic analysts note that the PLA’s predominance persists.[40] PLA ground force officers still dominate leadership of the new commands especially the eastern, western, and southern (see table 1). And they are given the majority of the promotions: since the beginning of the reforms, Xi has promoted 20 officers from the ground force, ten from the PLAAF, and four from the PLAN to the positions of generals.[41] Their continued dominance suggests the promotions have been used to placate the officers, who may have resisted the PLA’s joint command as it threatened vested interests, including the anti-corruption drive.[42] It then seems that Xi may have diluted the intensity of the reforms in some places to ensure that the overall train of PLA reforms is not derailed.

Table 1: Leadership of PLA Theatre Commands

| Command | Commander | Political Commissar |

| Eastern Theatre Command, Nanjing | General He Weidong (PLA Ground Force) | General He Ping (PLA Ground Force) |

| Western Theatre Command, Chengdu | General Wang Haijiang (PLA Ground Force) | General Li Fengbiao (PLA Ground Force) |

| Central Theatre Command, Beijing | General Lin Xiangyang (PLAAF) | General Zhu Shengling (PLA Ground Force) |

| Northern Theatre Command, Shenyang | General Li Qiaoming (PLAAF) | General Fan Xiaojun (PLAAF) |

| Southern Theatre Command, Guangzhou | Wang Xiubin (PLA Ground Force) | General Wang Jianwu (PLA Ground Force) |

Source: Gateway House Research

3. Upending ground forces’ dominance through demobilisation

After its debacle in the 1979 Vietnam war, Deng criticised the PLA as bloated and needing disciplinary measures. Therefore, he ordered one of the largest demobilisations in PLA’s history, with active personnel cut from over 6 million (1975) to over 4 million (1982).[43][44] In the current reforms, the PLA has cut more than 300,000 personnel. Overall, since the 1970s, China has cut over 4 million personnel, mainly within the Ground Force, while enhancing the size of the PLAN and the PLAAF.[45]

This demobilisation of troops, especially of the infantry, reflected the fundamental revision of the earlier military doctrines that China no longer required substantial ground forces to defend its territory.[46] In other words, the reduced quantity of the PLA troops was to be “compensated by increased quality” of soldiers and equipment. This was particularly evident in the case of the PLAN, where evolving threat perceptions from the U.S. led the PLA to opt for long-range naval aviation and offensive submarine capability.[47][48]

4. Establishing new forces for better “integration” and “informatisation”

Also, as part of the reforms, two new services were created: Strategic Support Force (SSF, 2015) and the Joint Logistics Support Force (JLSF, 2016).

- SSF is the cyber, space, and electronic warfare service branch of the PLA. It’s focus on emerging technologies points to China’s recognition of the global trend that “informatisation” or information-based/data-driven combat operations are the core of contemporary military advancement.[49] The SSF reports directly to the CMC and not to any of the theatre commands, enabling joint operations for all the theatre commands through the CMC, acting as their “information umbrella.”[50] Its creation has improved the PLA’s ability to fight information wars vis-à-vis its adversaries.[51] The SSF administers two deputy theatre command-level departments: the Space Systems Department, responsible for military space operations and the Network Systems Department, responsible for information operations like cyberattacks and cyber espionage campaigns, for which China has gained notoriety in recent years.[52]

- JLSF: It was created to manage the implementation of a joint logistics support system. It comprises the support forces for inventory and warehousing, medical services, and transport.[53] In addition, it works closely with the theatre commands to provide the appropriate general logistics support as required.[54] The outbreak of COVID-19 proved to be the first test for JLSF’s logistical capabilities. The force is headquartered in Wuhan (at Wuhan Joint Logistic Support Base)—the epicentre of the initial outbreak of COVID-19 in 2019-20. Therefore, it had an important role to play in transporting medical personnel, equipment and other supplies and working with the civilian companies to provide logistical support.[55] It also delivered Chinese COVID-19 vaccines to China’s allies like Pakistan and Cambodia. Western analysts like Meia Nouwens have assessed JLSF’s performance in executing logistical operations during the pandemic as “reasonably effective”.[56]

The following section briefly looks at China’s efforts to attain a lead in emerging technologies in order to reduce the capability gap with the West.

Pursuit of emerging technologies

Cyber and space capabilities: China has used the newly established SSF to build advanced space and offensive cyber capabilities. The SSF’s Space Systems Department has consolidated military space functions, including rocket launch, telemetry, tracking, control, satellite communications, space intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance.[57] The Network Systems Department has integrated and strengthened signals intelligence, cyber espionage, computer attack, electromagnetic warfare, and psychological operations, making the SSF a formidable offensive force.[58]

According to the U.S. intelligence community, China’s cyber espionage operations have included compromising telecommunications firms like Huawei and ZTE, which have provided opportunities for intelligence collection abroad.[59] For instance, in April 2019, telecommunications company Vodafone Group revealed that it had found security vulnerabilities with Huawei equipment deployed for its fixed-line phone network in Italy. These vulnerabilities probably gave Huawei unauthorized access to the carrier’s internet traffic and call data.[60] Likewise, in August 2020, a report from the Australian government and Papua New Guinea’s National Cyber Security Centre noted that the latter’s National Data Centre, built by Huawei in 2018, was marred by weak cybersecurity which exposed confidential government data to theft.[61]

Drones and unmanned aerial and underwater capabilities: China has pursued the research and development of drones and unmanned aerial and underwater capabilities with an eye on its benefits during combat and reconnaissance. It has had some notable successes: the PLAAF recently unveiled its largest drone, the WZ-7 “Soaring Dragon” high-altitude, long-range drone.[62] It has also developed and deployed a fleet of underwater Sea Wing drones in the Indian Ocean for naval intelligence purposes.[63] Currently, China is developing a supersonic drone WZ-8 as well as swarming drone capability. Research initiatives like these funded by China’s tech ecosystem that’s blended with the military system ensure that the PLA has the edge over the other militaries in the region and beyond.

Software-first dual-use technologies: In similar vein, through fair means and subterfuge, China has made great strides in software-first dual-use technologies like artificial intelligence, deep learning, and facial recognition. Besides, its own laboratories, the PLA has also utilised its domestic technology giants like Alibaba, SenseTime, and Megvii for developing the needed algorithms.[64]

The CCP has deployed these technologies for external defence as well as internal security purposes. For instance, many of these companies have been used for targeted facial recognition, artificial intelligence, big data, and genetic testing against its Uighur population in Xinjiang.

The next section sets out the implications of the above-discussed PLA reforms for the region, with a focus on India.

Implications of China’s military modernisation for the region

Since the undertaking of military reforms, Chinese foreign policy has increasingly taken an assertive tone vis-à-vis its neighbours like India, Taiwan, Japan, and the southeast Asian neighbours like Vietnam.[65]

Military balance against India: The military reforms and modernisation of the PLA strengthen China’s coercive capabilities. The reforms give the PLA the ability to fight decisive wars, and in some cases as cyber, cripple the enemy without firing a shot. This adds to the already large power differential between the Chinese military and other regional militaries, including India.

U.S. strategic analysts, Joel Wuthnow and Phillip Saunders speculate that the transformation following the military reforms might prove “sufficiently disruptive” to reduce the PLA’s ability to launch and sustain major combat operations. But India’s experience with China in the last five years has proved otherwise.[66] Since the ascent of Xi, India has seen PLA’s increased assertiveness beginning with the 2013 Depsang Valley incursion in Ladakh, which peaked with the ongoing border stand-off in Ladakh. During this ongoing stand-off, PLA’s enhanced effectiveness in executing joint combat operations and moving logistics is evident by the rapid deployment of upgraded versions of armoured vehicles, self-propelled howitzers, and heavy rocket launchers, along with a host of radar systems through the combined air defence system.[67][68] Similar Chinese aggression is also evident in case of other neighbours of China—Taiwan, the South East Asian neighbours with whom China has a maritime dispute in the South China Sea, and Japan over the Senkaku islands. In response to China’s military reforms as well as the global trend of militaries moving towards jointness and information-based operations, India has commenced its own military reforms. This includes establishing the tri-service Defence Cyber Agency and Defence Space Agency in 2019, appointment of the Chief of Defence Staff in 2020, and the proposed move towards theatre commands. These reforms have a longer gestation period. They will also necessarily have to tackle the protracted rivalry between the three services and the inherent resistance such jointness evokes from the services.[69]

Maritime contestation: China’s military modernisation has created an enhanced PLA Navy presence in the Indian Ocean, as seen by the reports of repeated docking of the PLAN nuclear submarines at the Colombo port in Sri Lanka and the Gwadar and Karachi ports in Pakistan. China has also augmented its presence in the Indian Ocean by participating in anti-piracy operations. Between 2008-2018, China dispatched 30 anti-piracy task forces in the Indian Ocean,[70] established the overseas military base in Djibouti in 2016, and enhanced its blue-water naval capabilities. With these, the PLA can project its power far beyond the Chinese mainland. China has utilised these to protect its investment under the Belt and Road Initiative and citizens overseas as acknowledged by the 2019 white paper.[71] According to the U.S. Department of Defence, China may be considering opening additional overseas bases, enabling the PLA to project and sustain power at greater distances.[72]

In response to China’s growing submarine operations in the Indian Ocean, the Indian Navy has substantially augmented its anti-submarine warfare capabilities—beginning 2013, it acquired the P8i maritime reconnaissance aircraft and in 2021, the MH-60 anti-submarine helicopters from the U.S., the anti-submarine warfare drills of the Malabar naval exercise.

Enhanced malicious cyber activities: China’s augmented cyber capabilities through the SSF is its increased offensive cyber operations, which has amplified in recent years. India and other neighbours of China have been at the receiving end of the expanded Chinese malicious cyber activities, mainly directed against its critical infrastructure. The only way for India to protect itself is to enhance capabilities through investments in cybersecurity and emerging technologies. India has made cybersecurity a policy priority and is developing the necessary safeguards to better protect itself. But the persistence of Chinese malicious cyber activities requires an even greater effort and also enlisting like-minded partners in the Indo-Pacific.

Conclusion

India’s first Chief of Defence Staff, the late General Bipin Rawat had recently remarked that China is the “biggest security threat” facing India.[73] India will have to take a long view of China’s transformed military power and expedite and adjust its defence reforms to achieve the same results. Implementing such reforms requires greater political management of the forces and reduced interference from the civilian bureaucracy. India must optimise its limited budgetary resources, and intensify its on-going force restructuring initiatives, including integrating the three services and adding to its power projection capabilities.

Keeping in view China’s focus on reducing the role of its ground forces, India too must invest more in aviation and naval assets since these will afford India enhanced power projection capability. At the heart of China’s military reforms and modernisation is its robust defence-industrial base in the aerospace, missiles and ship-building sectors. Therefore, domestic defence-industrialisation has a critical role in India’s own military advancement. The government has been encouraging a greater involvement of the private sector in defence manufacturing. To encourage them further, India will have to expedite its defence procurement process and expand support innovation in emerging technologies.

Sameer Patil is former Fellow, International Security Studies, Gateway House.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2022 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References:

[1] Bates Gil and Adam Ni, China’s Sweeping Military Reforms: Implications for Australia, Security Challenges, Vol. 15, No. 1, pp. 33-46

[2] Roderick Macfarquhar and Michael Schoenhals, Mao’s Last Revolution, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge Massachusetts and London, England, 2006, pp. 48-49

[4] Leo Y. Liu, “Army-Party Balance of Power Since 1969”, China Report, July-August 1976, Vol. XII, No. 4, pp. 3-9.

[5] David Shambuagh, “The People’s Liberation Army and the People’s Republic at 50: Reform at Last”, The China Quarterly, Sept. 1999, no. 159, pp. 660-672.

[6] Srikanth Kondapalli (2002) Towards a lean and mean army: Aspects of China’s ground forces modernisation, Strategic Analysis, 26:4, 461-477

[7] Zhang Jian, “Towards a ‘World Class’ Military: Reforming the pla under Xi Jinping” in Golley, Jane, Linda Jaivin, Paul J. Farrelly, and Sharon Strange, eds. Power. China Story Yearbook series, ANU Press, 2019.

[8] “Full text of Hu Jintao’s report at 18th Party Congress”, Xinhua, November 18, 2012, https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/744887.shtml.

[10] Xiaobing Li, A History of the Modern Chinese Army, The University Press of Kentucky, 2007, Lexington, Kentucky.

[11] Opinions of the Central Military Commission on Deepening the Reform of National Defense and the Army, 2016, https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E4%B8%AD%E5%A4%AE%E5%86%9B%E5%A7%94%E5%85%B3%E4%BA%8E%E6%B7%B1%E5%8C%96%E5%9B%BD%E9%98%B2%E5%92%8C%E5%86%9B%E9%98%9F%E6%94%B9%E9%9D%A9%E7%9A%84%E6%84%8F%E8%A7%81/19214222

[12] Interview with Dr. Bhartendu Singh, July 3, 2021

[13] Interview with Suyash Desai, June 30, 2021

[14] Interview with Dr. Srikanth Kondapalli, July 9, 2021

[15] Interview with Suyash Desai, June 30, 2021

[17] 颜慧, “新中国成立以来国防和军队改革实线及启示”, Implementation and Enlightenment of the National Defense and Army Reforms since the founding of New China – Yan Hui https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFDLAST2021&filename=JSLS202005010&v=RumAqUfrnMNYSuJZ%25mmd2B1GqHkI6QRrt4Z0uOF6f1nSG3WLC9URWY6QbiT8d1KZOSpC3

[18] Deng Yifei, “Deepening reform is the only way to strengthen the army”, 2018, Social Science Series I, DOI: 10.28072/n.cnki.ncgfb.2018.001777

[19] Dai Kun, “An Analysis of the Characteristics of Xi Jinping’s Strategic Thinking of Reforming and Strengthening the Army since the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China”, Social Science Series I, 2017, DOI: 10.13736/j.cnki.zgsjzswdxxb.2017.0111

[20] Macabe Keliher and Hsinchao Wu. “Corruption, Anticorruption, and the Transformation of Political Culture in Contemporary China.” The Journal of Asian Studies 75, no. 1 (2016): 5–18

[22] http://www.ipcs.org/comm_select.php?articleNo=5779

[23] “China’s Defense Budget,” GlobalSecurity.org, accessed April 28, 2021, https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/china/budget-table.htm.

[25] https://jamestown.org/program/chinas-domestic-security-spending-analysis-available-data/

[26] https://jamestown.org/program/chinas-domestic-security-spending-analysis-available-data/

[27] https://www.csis.org/analysis/understanding-chinas-2021-defense-budget

[28] http://eng.mod.gov.cn/leadership/index.htm

[29] http://www.scio.gov.cn/32618/Document/1461755/1461755.htm

[30] Interview with Dr. Srikanth Kondapalli, July 9, 2021

[31] Phillip C Saunders and Joel Wuthnow, China’s Goldwater Nicholas? Addressing PLA Organisational Reforms, Institute of National Strategic Studies,

[32] China Aerospace Studies Institute, In Their Own Words: Foreign Military Thought – Science of Military Strategy (2013), Air University, 2021, https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/CASI/Display/Article/2485204/plas-science-of-military-strategy-2013/, pp. 323-324

[33] Interview with Dr. Srikanth Kondapalli, July 9, 2021

[34] Interview with Dr. Atul Kumar, June 27, 2021 and Suyash Desai, 2021

[35] https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2016-02/01/content_23346907.htm

[36] Joel Wuthnow and Phillip C Saunders, Chinese Military Reform in the Age of Xi Jinping: Drivers, Challenges and Implications, p. 4

[37] Interview with Rukmani Gupta, July 2, 2021

[38] Interview with Suyash Desai, June 30, 2021

[39] https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/china/mr.htm

[40] Interview with Dr. Srikanth Kondapalli, July 9, 2021

[41] https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/china-military-watch-11/

[42] Interview with Dr. Atul Kumar, June 27, 2021

[43] Edward C. O’Dowd, Chinese Military Strategy in the Third Indochina War, Routledge, Abingdon, Oxon, 2007

[44] Srikanth Kondapalli, China’s Military: The PLA in Transition, Knowledge World-IDSA, New Delhi, 1999, pp. 118-146.

[45] Sameer Patil, “New Sun on the Horizon: The Rise of the PLA Navy”, China Report, Vol. 43, No. 4, 2000, pp. 521-529.

[46] Yitzhak Shichor. (1996). Demobilization: The Dialectics of PLA Troop Reduction. The China Quarterly, 146, p. 344

[47] Srikanth Kondapalli, China’s Naval Power (New Delhi: Knowledge World, 2001), p. 71

[48] Peter Howarth, China’s Rising Sea Power: The PLA Navy’s Submarine Challenge (London and New York: Routledge, 2006).

[50] https://jamestown.org/program/the-peoples-liberation-army-strategic-support-force-update-2019/

[52] Elsa B. Kania and John K. Costello, “The Strategic Support Force and the Future of Chinese Information Operations,” The Cyber Defense Review 3, no. 1 (2018): 105–22.

[53] http://english.www.gov.cn/news/topnews/201910/01/content_WS5d92f867c6d0bcf8c4c147b6.html

[55] http://eng.mod.gov.cn/focus/2021-10/09/content_4896377.htm

[56] https://www.iiss.org/blogs/military-balance/2020/05/china-armed-forces-covid-19-pla

[57] https://jamestown.org/program/the-peoples-liberation-army-strategic-support-force-update-2019/

[58] https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/stratperspective/china/china-perspectives_13.pdf

[59] https://www.dni.gov/files/ODNI/documents/assessments/ATA-2021-Unclassified-Report.pdf

[63] https://www.forbes.com/sites/hisutton/2020/03/22/china-deployed-underwater-drones-in-indian-ocean/

[64] https://ipvm.com/reports/alibaba-uyghur

[65] Interview with Dr. Bhartendu Singh, July 3, 2021

[66] Joel Wuthnow and Phillip C Saunders, Chinese Military Reform in the Age of Xi Jinping: Drivers, Challenges and Implications, p. 42

[67] https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202105/1223613.shtml

[69] https://www.gatewayhouse.in/chief-of-defence-staff/

[70] https://thediplomat.com/2018/12/china-dispatches-new-naval-fleet-for-gulf-of-aden-escort-mission/

[71] The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, China’s National Defense

in the New Era, Foreign Languages Press Co. Ltd., Beijing, China, 2019

[72] https://media.defense.gov/2021/Nov/03/2002885874/-1/-1/0/2021-CMPR-FINAL.PDF

List of Indian interviewees:

1. Dr. Srikanth Kondapalli

2. Dr. Atul Kumar

3. Dr. Bhartendu Kumar Singh

4. Rukmani Gupta

5. Suyash Desai