For the updated version of this map, click here.

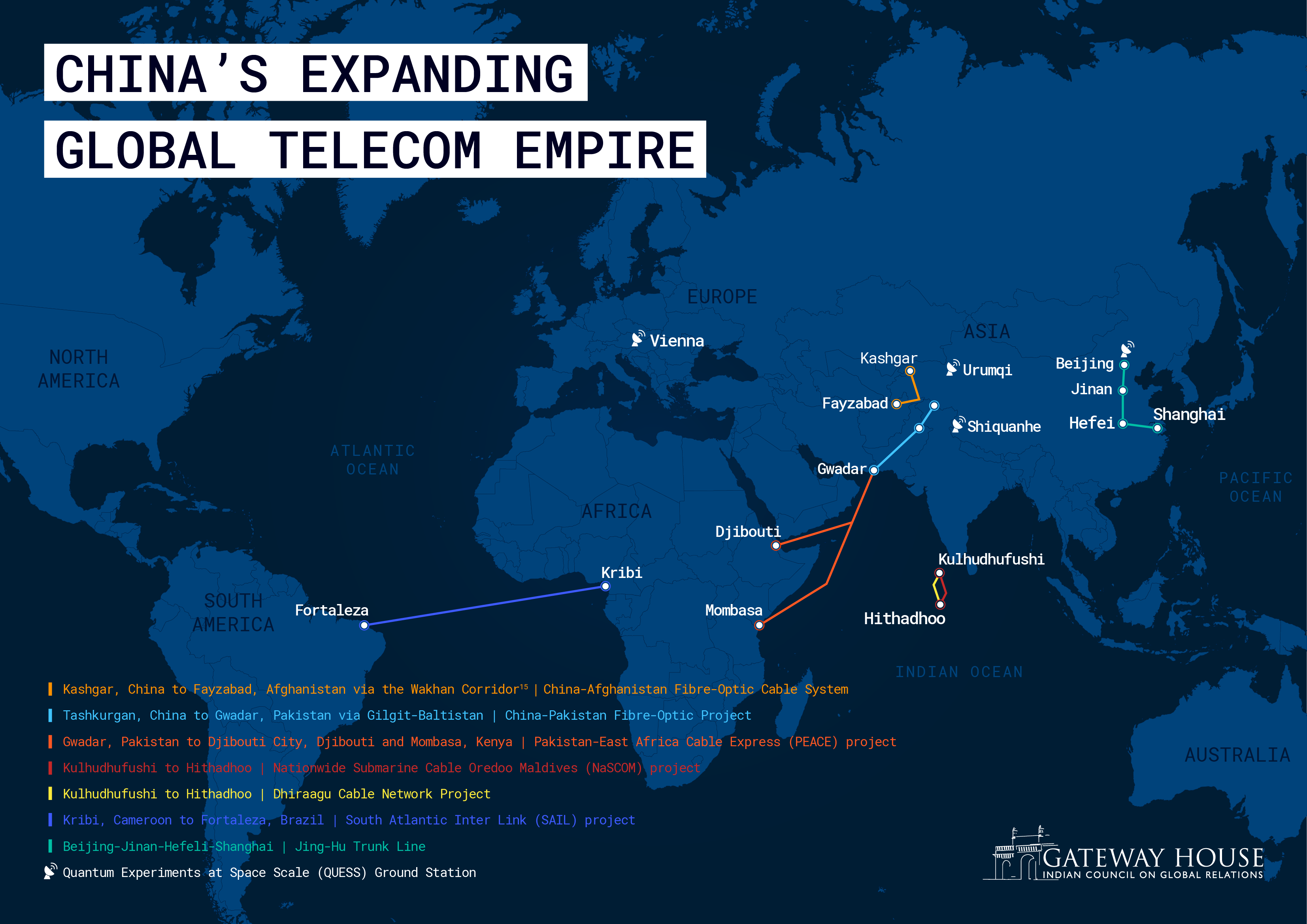

When, in 2016, Huawei, a prominent player in China’s military-industrial complex, laid submarine cables, connecting the scattered Maldivian atolls with an almost 1200-km long communications cable network [1], other countries showed little concern. Its decision to install a land-based cable network from Tashkurgan in China through the Khunjerab Pass in Gilgit-Baltistan to the strategically important port facilities China is building in Gwadar in Pakistan as part of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) [2], also attracted scant attention – even though Huawei is installing the Pakistan-East Africa Cable Express, which will connect Gwadar, China’s cordoned military-commercial colony in Pakistan, to the PLA’s new and acknowledged military base in Djibouti by 2019 [3].

As is often the case with China, determining where commercial interests end and military ones begin can be challenging. There is ample evidence that China has set out to be a big player in the global telecommunications business. Chinese entities have tested a sophisticated satellite link to Europe, for instance. They are laying a 6000-km submarine cable – the South Atlantic Inter Link (SAIL) – between Cameroon and Brazil [4], which now makes China only the third country (after the United States and Japan) to offer such a telecommunications connection between Africa and South America.

There is no doubt that the Chinese see telecommunications as a new frontier in their military doctrine. In 2015, the PLA’s Zhejiang Provincial Military Command introduced a new-generation submarine cable-laying ship [5]. And a year later, the PLA’s Naval University of Engineering established a research and development laboratory for underwater optical networks collaborating with the Chinese private sector [6].

Such investments appear to reflect, at least in part, the growing importance of ‘informationised’ (See footnotes 13 and 14) operations in Chinese military doctrine.

Informationised operations allude to the utilisation of information communication technology (ICT) as a weapon in the battlefield. Over the past three decades, battlefields have become increasingly inundated with ICT networks. The PLA is steadily developing capacities to dominate such networks and surpass Russian and American capabilities in the domain – and it has a maturing stratagem for it.

In May 2015, the Chinese Ministry of National Defence published a white paper, proposing the enhancement of the PLA’s ability to ‘win informationised local wars’ [7]. The paper implies the Chinese emphasis on research and development of ICT systems and their growing role in warfare. Further confirmation of China’s evolving priorities came when, in November 2015, the chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC), Xi Jinping, merged departments dealing with cyber, space, electronic, and information warfare activities into a single joint operations division, known as the PLA Strategic Support Force (PLASSF) [8] entirely under the command of the CMC.

Another part of China’s rapidly modernising and ‘informationised’ military infrastructure is its ‘quantum ICT systems’. Based on the principles of quantum mechanics, these systems can transmit data with extremely secure encryption and at high speeds via satellites or through cable networks [9].

In a major technology demonstration in 2017, a consortium of Chinese R&D laboratories connected its cities of Beijing, Jinan, Hefei, and Shanghai with an almost 2000-km long quantum-ICT cable network [10]. It has installed a restricted metropolitan area quantum-ICT cable network for a select number of offices in the city of Jinan [11]. The same year, the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) through its Mozi satellite transmitted an inter-continental video call, encrypted with a novel quantum cryptography protocol, between ground stations in Beijing and Vienna, Austria [12]. Although most of these technologies are currently in nascent stages of R&D, they nevertheless could be utilised by the PLASSF.

Beijing also has built a quantum satellite ground station at Shiquanhe in Ngari province in Tibet [13]. Ngari is less than 100 km east of the India-China Line of Actual Control. A quantum satellite ground station, located so close to a demarcation line, can be used for covert communications between the PLA’s Western Theatre Command and the forward military deployments against India.

The military utility of quantum communication systems does not end there. China’s autonomous enclaves, like Gwadar and Djibouti, could also possess quantum satellite ground stations or a metropolitan area network of quantum ICT cables, like the one installed in Jinan. Such ICT-connected enclaves can serve military, political, industrial, and economic intelligence and counterintelligence management operations [14] [15].

How should other countries respond? That’s a vexing question. There are no precedents for a combined regulatory response. The issue hasn’t arisen in the past because existing regulatory systems are based on older technologies that are potentially hackable, and thus do not provide their builders the same kind of potential military edge that China may reap from the impenetrable newer technologies it is deploying today.

Similarly, military planners in countries like India have not addressed the issue, perhaps because they haven’t perceived a threat in the past. The U.S., which pioneered informationised warfare during its wars in Iraq, has secure military communications systems that lie completely outside the commercial sphere. But with China moving ahead to deploy systems that could give it an advantage in informationised warfare, it’s time other countries, including India, start addressing the issue.

A good place to start will be for New Delhi to establish a strategic operations force under a unified defence command, [16] capable of matching the PLASSF’s abilities to plan and coordinate next-generation military and intelligence operations.

Chaitanya Giri is Fellow, Space and Ocean Studies, Gateway House.

For the updated version of this map, click here.

Click here to view our repository on the Arc of India’s Border Security.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in or 022 22023371.

© Copyright 2018 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References

[1] ‘Ooredoo and Huawei Marine inaugurate National Submarine Cable in Maldives’, Huawei News, 16 December 2016, <http://www.huawei.com/en/press-events/news/2016/12/Ooredoo-Huawei-Submarine-Cable-Maldives>

[2] People’s Republic of China National Development & Reform Commission, Long Term Plan for China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (2017-2030), December 2017, <http://cpec.gov.pk/brain/public/uploads/documents/CPEC-LTP.pdf>

[3] ‘Huawei Marine and Tropical Science commences work on the construction of the PEACE submarine cable linking South Asia with East Africa’, Huawei News, 6 November 2017, <http://www.huawei.com/en/press-events/news/2017/11/PEACE-Submarine-Cable-SouthAsia-EastAfrica>

[4] ‘Huawei Marine is contracted to build Cameroon-Brazil trans-Atlantic submarine cable to connect Africa to Latin America’, Huawei Marine News, 22 October 2015, <http://www.huaweimarine.com/en/News/2015/press-releases/pr20151022>

[5] Y. Jianing, ‘PLA Army’s new cable-laying ship starts service’, China Military Online, 27 March 2015, <http://english.chinamil.com.cn/news-channels/china-military-news/2015-03/27/content_6417148.htm>

[6] Hengtong Optoelectronics, Annual Report 2016, 22 April 2017, <http://finance04.com/sbdm/stock/share,disc,2017-04-22,600487,0000000000000hwtd1.shtml>

[7] Information Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China, China’s Military Strategy, 26 May 2015, <http://eng.mod.gov.cn/Press/2015-05/26/content_4586805.htm>

[8] J. Wuthnow & P.C. Saunders, Chinese military reforms in the age of Xi Jinping: Drivers, challenges, and implications: China Strategic Perspectives, No. 10. Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, Institute for National Strategic Studies, National Defense University, Washington DC, USA, March 2017, <http://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/stratperspective/china/ChinaPerspectives-10.pdf?ver=2017-03-21-152018-430>

[9] J-G. Ren et al., ‘Ground-to-satellite quantum teleportation’, Nature, Vol 549, pp. 70-73, 2017, <https://www.nature.com/articles/nature23675?WT.ec_id=NATURE-20170907&spMailingID=54864391&spUserID=MTgyMjI3MTU3MTgzS0&spJobID=1244089361&spReportId=MTI0NDA4OTM2MQS2>

[10] R. Courtland, ‘China’s 2,000-km quantum-link is almost complete’, IEEE Spectrum, 26 October 2016, <https://spectrum.ieee.org/telecom/security/chinas-2000km-quantum-link-is-almost-complete>

[11] Y. Yang, ‘China trial paves way for ‘unhackable’ communications network’, Financial Times, 10 July 2017, <https://www.ft.com/content/899458ca-655c-11e7-8526-7b38dcaef614>

[12] A. Nordrum, ‘China demonstrates quantum encryption by hosting a video call’, IEEE Spectrum, 3 October 2017, <https://spectrum.ieee.org/tech-talk/telecom/security/china-successfully-demonstrates-quantum-encryption-by-hosting-a-video-call>

[13] Brig. A. Sahgal & Brig. V. Anand, ‘Revolution in Military Affairs and Jointness’, Journal of Defence Studies, Vol. 1, 2007, <https://idsa.in/jds/1_1_2007_RevolutionInMilitaryAffairsAndJointness_ASahgal>

[14] J. Costello, ‘The Strategic Support Force: China’s Information Warfare Service’, China Brief, Vol. 16, 8 February 2016, <https://jamestown.org/program/the-strategic-support-force-chinas-information-warfare-service/>

[15] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, ‘Afghanistan and China Sign Optic Fiber Agreement’ Regional Economic Cooperation Conference on Afghanistan, 26 April 2017, <http://recca.af/?p=2387>

[16] Adrianwalla, Xerxes, ‘India: A unified defence command’, Gateway House, 10 April 2012, <https://www.gatewayhouse.in/india-unified-defence-command/>