Sri Lanka is a case study of how large Chinese investments can go terribly wrong for a host economy. Large foreign loans, contracted at high interest rates, have pushed the country into a debt trap. This has already forced Colombo to hand over the Hambantota Port to China Merchant Port Holdings at the end of 2017 with a 99-year lease that mirrored the 99-year handover of Hong Kong to Britain during the colonial period.

China accounted for 30% of all Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in Sri Lanka from 2012-16 – four times the FDI from India – and China is now the top source for Sri Lanka’s imports, displacing India.

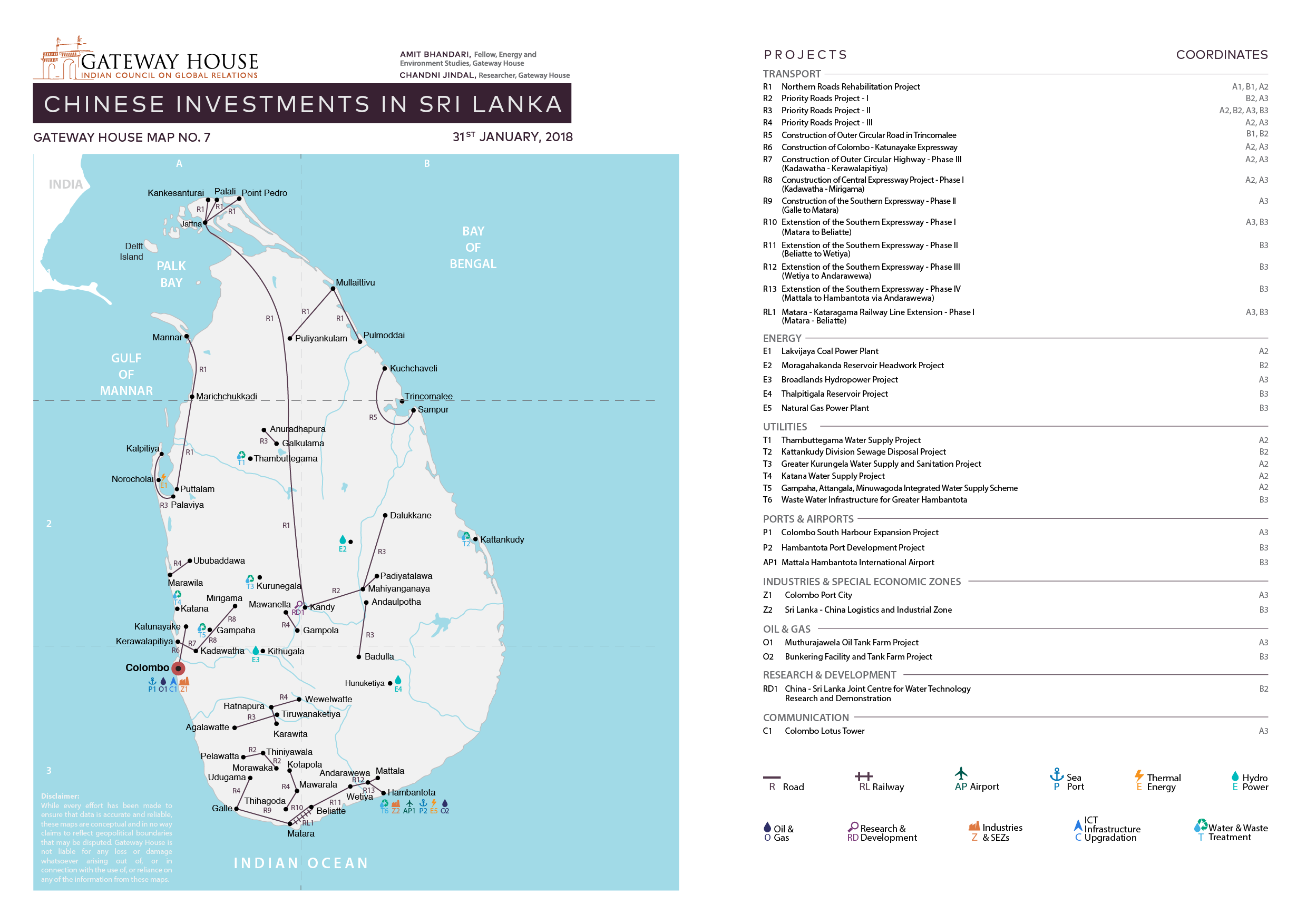

The Gateway House map of Chinese investments in Sri Lanka shows how deep China’s presence in the Sri Lankan economy is: Chinese debt and equity are funding more than 50 projects worth more than $11 billion. Most are roads and water treatment plants, but the largest projects are the Hambantota Port, the Colombo Port City and the Lakavijaya thermal power plant – all three funded by Chinese government-owned banks and being built by Chinese contractors.

These investments come at a high cost. Interest rates on some of the Chinese loans are as high as 6.5% per annum compared to rates of 2.5%-3% for loans made by the Asian Development Bank or the World Bank. Since the financier and the contractor are both owned by the Chinese government, there is a possibility that project costs are being padded, exacerbating the debt load.

High Debt Load

During 2017, Sri Lanka’s government spent 83% of its revenues on debt repayment, a quarter of which was for foreign borrowings. The country’s external debt repayments are projected to double from $2.1 billion in 2017 to $3.3-$4.2 billion annually from 2019-22. It is not surprising that Sri Lanka chose to convert some of this debt into equity and hand over Hambantota to China Port Holdings.

Chinese investment hasn’t happened in a vacuum. China-Sri Lanka ties were forged during Sri Lanka’s civil war, when China was one of the few reliable arms suppliers to the government. China also provided political cover, using its veto to stop UN resolutions targeting Sri Lanka. The agreement to develop the Hambantota Port was signed during this period – in 2007.

Concerns

From the Indian perspective, China’s dominant role in Sri Lanka raises multiple concerns:

- Colombo Port handles over 30% of India’s container traffic, so a disruption there could harm India’s foreign trade. China Merchant Port Holdings, a company owned by the Chinese government, has an 85% stake in the expansion at Colombo.

- China has supplanted India as Sri Lanka’s top source of imports. Chinese investments in infrastructure, such as ports and roads, open the Sri Lankan market for construction equipment, steel and trucks to Chinese companies, reducing the economic space for India.

- Assets, such as the Hambantota Port, could have military uses. The current Sri Lankan government has prohibited military use of the port, but a more China-friendly government could change this in the future.

The Challenge

India continues to have significant economic ties with Sri Lanka – in tourism, trade and investment. India needs to continue building on these ties. For instance, it could:

- Integrate the power-grids of Sri Lanka and India via an undersea cable, as has been suggested by both sides and the Asian Development Bank in the past. This will give Sri Lanka an alternative to building thermal power plants with Chinese funds.

- Help Sri Lanka increase its capacity to refine petroleum. State-owned Indian Oil has signed a proposal to build a new oil refinery in Sri Lanka. This project must be expedited since Sri Lanka is also discussing the matter with Chinese firms.

To maintain control over its own external trade, India must respond to growing Chinese control over Sri Lankan ports. The island nation’s population isn’t large enough to support the ports of Colombo and Hambantota, so it will be looking to handle a growing share of Indian cargo traffic. The majority of Colombo’s container traffic is transhipped to India, and Hambantota will be eager to handle India traffic too. India needs to develop its own transhipment ports. The Sagarmala Project of the Shipping Ministry identifies Vizhinjam (Kerala) and Enayam (Tamil Nadu) as potential transhipment ports; these must be expedited.

This map is part of a larger book on Chinese Investments in India’s Neighbourhood. To see the project description and place an order for the book, please click here.

Amit Bhandari is Fellow, Energy and Environment Studies at Gateway House

Chandni Jindal is Researcher at Gateway House

Visualized and mapped by Debarpan Das

This map was exclusively developed by Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2018 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.