In the last decade, India has gone from having a cash-based economy to one that primarily relies on digital payment systems. This has been achieved on the back of successful implementation of the Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yojana, the innovation of the Unified Payments Interface (UPI) real-time payment system and promotion of mobile payment services. A key enabler has been seeding of personal and biometric Aadhaar data with individual bank account information. Statistics from the National Payments Corporation of India showed that digital payment services have been rapidly expanding, with UPI crossing 1 billion transactions in October 2019.[1]

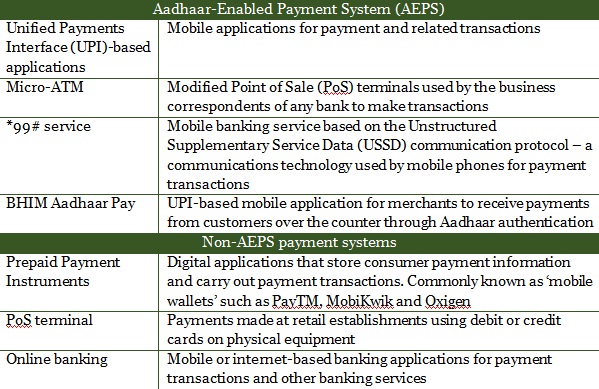

Table 1: Nodes in India’s digital payments system

This rapid expansion of digital payment systems is happening at a time when cyber security threats to payment systems are increasing globally, with organised criminal syndicates committing cyber-crimes. In some cases, foreign governments have used these syndicates and other such proxies to target other states’ financial institutions and banks. The example of the North Korea-backed Advanced Persistent Threat (APT)-38 cyber operation to repeatedly target the inter-banking transaction systems (operated by the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication, SWIFT) illustrates how rogue state actors are netting the proceeds of cyber-crime.[2]

India is not immune from these threats. A review of the major cyber-attacks on India’s computer networks since 2010 demonstrates that the financial sector has been the most hit by unauthorised access and data breach. The most serious of these was the malware attack on Hitachi Payment Services in 2016,[3] which resulted in losses worth Rs. 1.3 crore and forced 19 Indian banks to replace more than 30 lakh debit cards.[4]

Another emerging trend is that attackers are targeting not just the centralised databases of banks, but also individual users and banking professionals to gain illegal access: the 2016 Union Bank of India breach allowed hackers to siphon $170 million from its foreign-exchange account.[5] A timely intervention by the bank successfully retrieved the stolen money. But in many other cases, the money is only partially recovered, such as the City Union Bank breach of 2018,[6] or worse, simply lost, as in the case of the Cosmos Bank fraud of 2018.[7]

India has not publicly attributed these cyber-attacks to other countries. But there is sufficient anecdotal and technical evidence, which suggests the involvement of state actors in some of these hostile acts. For instance, the modus operandi followed in the attack on Cosmos Bank implicates North Korea’s APT-38 operation.[8] In addition, senior police officials have repeatedly pointed to India’s painful experience obtaining data that is stored outside the country for daily occurrences of cyber-crimes.[9] Varying legal practices add another layer of complication, despite the existence of Mutual Legal Assistance Treaties.

Interviews with representatives of banks, payment-gateway companies, and cyber-security professionals reveal that there are specific vulnerabilities within the various nodes of India’s retail digital payment systems. Major vulnerabilities include: unsecured mobile phones, lack of updated systems and deficient cyber hygiene. In fact, the payment industry has flagged deficient cyber hygiene – practices to ensure safe online behaviour – as the weakest security link in payment systems. The success of social engineering techniques – phishing and vishing (using telephones to trick individuals into divulging critical personal or financial information) – demonstrates why cyber hygiene is critical. Anecdotal evidence suggests hackers deploy social engineering techniques to target bank employees as in the case of the Union Bank of India breach in 2016.

Other vulnerabilities are: centralised data storage, insider threat and lack of, or insufficient, encryption. As India’s dependence on digital payment systems deepens, particularly through the UPI and mobile wallets, these vulnerabilities are expanding the threat landscape for cyber-attacks, such as spoofing of identities, malware injection, ‘Distributed Denial of Service’ and ‘Man in the Middle’ attacks.

The payments industry has implemented several policy measures in response to these ever-expanding threats. These include:

1) The Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) cyber security frameworks, guidelines and advisories for banks and other payment-system operators. The RBI has also mandated banks to set up a Security Operations Centre to detect cyber security incidents and report them to the Indian Banks-Center for Analysis of Risks and Threats (IB-CART).[10] It has also issued guidelines to store payments data in India;[11]

2) Globally-accepted industry standards such as the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard;[12]

3) SWIFT Customer Security Programme which focuses on the prevention of cyber-related fraud by improving information sharing within banks.[13]

Moreover, the government is setting up specialised agencies to bolster the security of digital payment systems. They are the Indian Cyber Crime Coordination Centre, which will monitor cyber-crimes, and a long-awaited Computer Emergency Response Team for the financial sector (CERT-FIN), which will report to CERT India.[14] However, establishment of CERT-FIN has proved difficult as many smaller banks are yet to have Security Operation Centres for the reporting of cyber security incidents.

Despite these important initiatives, information sharing within government agencies, the government and industry remains a major challenge. India lacks an enforcement mechanism at the government level, and its digital payment industry is not equipped with a dedicated national cyber security incident-reporting platform. The IB-CART, set up for reporting cyber threats, only covers the banking sector. Mobile wallet providers, which constitute a critical and growing part of the financial system, have no dedicated mechanism through which to report cyber security incidents, such as fraud or data breaches, other than to report them to the local police stations, where enforcement and punitive action are weak.[15]

To ensure resilience of payment systems and a greater level of cyber security, action on three levels is needed, government, business and diplomatic:

a) Government: The RBI must make reporting of data breaches mandatory for the industry. This needs to be accompanied by the expedited creation of a Computer Emergency Response Team for the financial sector to generate actionable intelligence on emerging cyber threats. Cyber hygiene education initiatives should be expanded to focus on emerging technologies and information-sharing security practices for government departments.

b) Business (industry): Payment processors should enable consumers to control data through a consent dashboard which will allow them to review, modify or delete their personal and payments data on websites such as e-commerce sites. The payment industry must create an industry-wide platform for information-sharing to share classified, unclassified and open source information on cyber-attacks and threat vectors.

c) Diplomatic (global): India should negotiate preferential and conditional data-sharing agreements with like-minded countries, which will ensure timely access to data for cyber-crime investigations. It should also take steps towards attributing cyber-attacks by revealing technical analysis of threat vectors and emphasise applicable legal frameworks.

India’s policy push for digital payments makes it an important global actor in the digital economy. So secure digital payment systems are vital for consumer confidence. If this security concern does not get due attention, expansion of the digital economy will face significant impediments.

You can read the full paper here.

Sameer Patil is Fellow, International Security Studies Programme, Gateway House.

Sagnik Chakraborty is Researcher, Cybersecurity Studies, Gateway House.

This article was exclusively written by Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2020 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References

[1] National Payment Corporation of India, ‘UPI crosses 1 BN transactions in October 2019’, 1 November 2019 <https://www.npci.org.in/sites/default/files/UPI%20crosses%201%20billion%20transactions%20in%20October%202019.pdf> (Accessed on 30 December 2019)

[2] Fraser, Nalani, Jacqueline O’Leary, Vincent Cannon and Fred Plan, ‘APT38: Details on New North Korean Regime-Backed Threat Group’, FireEye, 3 October 2018, <https://www.fireeye.com/blog/threat-research/2018/10/apt38-details-on-new-north-korean-regime-backed-threat-group.html> (Accessed on 12 January 2019).

[3] Hitachi, ‘Final investigation report completed; Hitachi Payment Services suffered breach due to sophisticated malware attack in mid-2016′, 9 February 2017, <https://www.hitachi-payments.com/src/HPY%20Press%20Release_V9.pdf> (Accessed on 21 June 2018).

[4] National Payments Corporation of India, ‘Statement pertaining to press reports on debit card compromise’, 20 October 2016, <https://www.npci.org.in/sites/default/files/Statementpertainingtopressreportsondebitcardcompromise.pdf> (Accessed on 15 June 2018).

[5] Saravade, Nandkumar and Bhalla, Ambuj, ‘Emerging trends and challenges in cyber security’, <https://rebit.org.in/whitepaper/emerging-trends-and-challenges-cyber-security> (Accessed on 30 December 2019 )

[6] CNBC-TV18, “City Union Bank cyber attack: Successfully retrieved/block money in 2 out of 3 cases”, 19 February 2018, <https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/companies/city-union-bank-cyber-attack-successfully-retrievedblock-money-in-2-out-of-3-cases-2510837.html> (Accessed on 26 January 2018).

[7] Cosmos Bank, “Official press release regarding the unfortunate attack on the Indian Banking Sector”, <https://www.cosmosbank.com/press-release/> (Accessed on 20 August 2018).

[8] FireEye, ‘APT38: Un-usual Suspects’, <https://content.fireeye.com/apt/rpt-apt38>, (Accessed on 21 May 2019), p. 5.

[9] Patil, Sameer, Interviews with Indian police officials, Mumbai, June 2017 and January 2019

[10] Reserve Bank of India, ‘Cyber Security Framework in Banks’, 2 June 2016,

[11] Reserve Bank of India, ‘Storage of Payment System Data’, 6 April 2018,

[12] Payment Standards Council, Maintaining payment security, <https://www.pcisecuritystandards.org/pci_security/maintaining_payment_security> (Accessed on 25 December 2018).

[13] SWIFT, “Customer Security Programme”, <https://www.swift.com/myswift/customer-security-programme-csp> (Accessed on 19 July 2019)

[14] Department of Economic Affairs, Ministry of Finance, Press Release on the Report of the Working Group for setting up Computer Emergency Response Team in the financial sector, 30 June 2017, <http://dea.gov.in/sites/default/files/Press-CERT-Fin%20Report.pdf> (Accessed on 25 December 2018).

[15] National Crime Records Bureau, Ministry of Home Affairs, Crime in India 2016, <http://ncrb.gov.in/StatPublications/CII/CII2016/pdfs/NEWPDFs/Crime%20in%20India%20-%202016%20Complete%20PDF%20291117.pdf> (Accessed on 19 August 2018), p. 435.