Next week’s Spring Meetings will be dominated by reactions to the World Bank’s updated reform roadmap. The proposed reforms are intended to set out how the World Bank can play a greater role in addressing shared global challenges alongside its mission to eradicate poverty and promote shared prosperity. A proposed $50 billion increase in lending over the next decade clearly falls short of expectations.

While the volume of lending is critical, how the World Bank lends matters too. The reform roadmap does touch upon its operations, but in a fairly limited way. It remains largely silent on how a 21st century World Bank could better address some of the long-standing frustrations that borrowers express about working with it and other multilateral development banks (MDBs).

Despite the operational model of MDBs demonstrably possessing many strengths, borrowers nevertheless see some drawbacks. Policy conditionality creates barriers to borrowing and can potentially shift priorities away from what countries and their citizens want, lending approval and disbursement processes can be lengthy, and advice and ideas are not always tailored to country needs. Thus far, none of these challenges are recognised in the roadmap. Even if all its reforms are implemented, the risk remains that client countries will still choose to borrow limited amounts from MDBs.

Building on the findings of an ODI survey of borrowing country officials and MDB staff, a review of the literature and two recent workshops with stakeholders (see summary here), we identify at least four issues that the roadmap – and indeed, all MDBs – must address to increase the uptake of MDB lending by borrower countries.

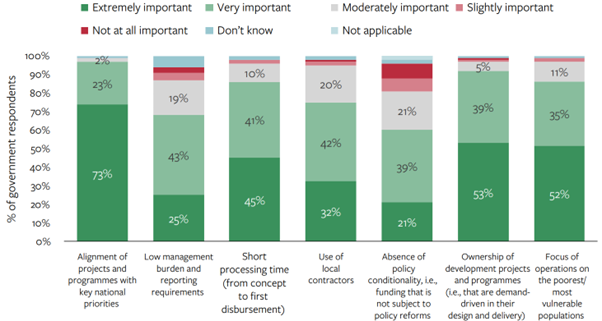

When asked about the relative importance of a range of MDB characteristics, nothing ranks more highly among borrowers than the alignment of MDB finance with national priorities. 96% of government respondents say it is either ‘extremely’ or ‘very’ important for programmes and projects to be closely aligned (Figure 1).

Source: Prizzon et al. (2022)

The emphasis on climate change in the roadmap has led to concerns that the proposed reforms are overly focused on the problems prioritised by high-income countries.

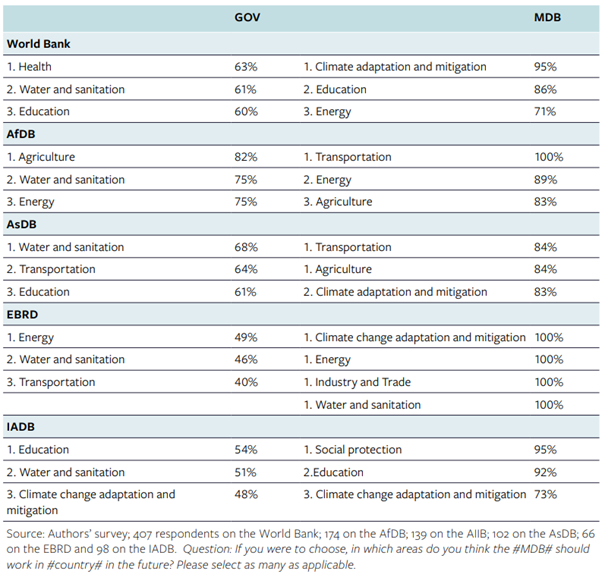

This is consistent with the findings of the ODI survey, which show that government officials see climate mitigation and adaptation as less of a priority than MDB staff do (Figure 2).

However, the survey also shows that borrowers clearly want to see MDBs (and especially regional MDBs) working in sectors that are either likely to be most affected by climate change (e.g. water and sanitation and agriculture) or that have a major bearing on future emissions pathways (e.g. energy and transport).

Source: Prizzon et al. (2022)

Scaling up lending for sustainable infrastructure is one way to marry a greater emphasis on climate with borrower priorities: it can support development ambitions in a climate-changed world. MDBs are well positioned to lend for infrastructure because they can offer ‘patient capital’ at lower-than-market rates and can support projects at scale. Between 2012 and 2021, however, MDB lending for infrastructure declined as a share of total lending, as shown by OECD data (Figure 3).

Source: OECD Creditor Reporting System

Note: data covers nine MDBs (African Development Bank, Asian Development Bank, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, Development Bank of Latin America, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, Inter-American Development Bank, Islamic Development Bank, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, and International Development Association). Economic infrastructure sectors include transport and storage, energy, and communications. Social infrastructure sectors include education, health, population policies and programmes, water and sanitation, and government and civil society.

MDBs also play an increasingly prominent role in lending during crises. They typically offer programmatic loans (rather than project-specific loans) to help cushion borrowers from the impact of crises. Such instruments have enabled MDBs to ramp up their overall lending in these critical periods.

Pausing policy conditionalities during a crisis would more closely align emergency finance with borrower needs. Government priorities inevitably change at times of crisis as attention shifts to short-term crisis management, but World Bank conditionalities have tended to stay focused on medium-term policy reforms. This is in contrast to the IMF’s emergency financing instruments, which are largely free of conditions.

Governments want quick access to finance: the ODI survey found that almost 90% of government respondents rank ‘short processing times (from concept to first disbursement)’ as very or extremely important. However, fewer than half of respondents think that MDBs are performing well in this area.

For many countries, borrowing from MDBs can be a complex and resource-intensive exercise. Approving projects involves multiple steps (including several country missions), each requiring lengthy preparation and internal reviews, while documents must be prepared and circulated in advance. Infrastructure lending can be especially complex to navigate. MDBs apply stringent environmental and social safeguards; these play a critical role in protecting vulnerable groups and the environment, but they often fail to provide the time and financial resources needed to follow them. The final decision is made by the MDB boards, which are often dominated by non-borrowing shareholders.

Borrowing countries must learn how to navigate the rules set up by the MDBs, which vary according to the lender and change over time. Borrowers are also fully responsible for bearing the costs of meeting MDB standards, even where governments face major resource constraints. This raises the effective cost of borrowing from MDBs and can discourage borrowers from taking out loans.

To effectively address borrowers’ concerns, MDBs could do much more to streamline their requirements and safeguards. For instance, they could harmonise their rules and procedures, and further delegate project approval to management (something that the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank already does). Much more of this process could be digitised rather than being paper-based. Safeguarding units also require proper resourcing. This might require non-borrowing shareholders to invest grant-based resources in specialist implementation teams who can help governments work through complex processes, especially in lower-income contexts.

Of the services that MDBs offer, the provision of technical assistance to facilitate the implementation of specific projects and policy advice to strengthen institutions are among the most highly valued. These are powerful tools: research shows that the World Bank has had greater influence in shaping the policy directions of middle-income borrower countries through its advisory and analytical services than through its financial offers.

However, only a third of government officials think that MDBs are responsive to client demands when providing technical assistance and policy advice. MDBs also struggle to adapt to local realities, and have a tendency to prioritise ideas and advice issued from headquarters at the expense of local expertise. Because policy advice is often geared towards enabling new project approvals (in the ODI survey, 70% of MDB staff recognise that advice tends to be combined with grants and loans), financial imperatives often determine the nature of advice. Furthermore, the analytical products offered by MDBs are not always suited to the realities of policy-making. Analysis often comes in the form of long, set-piece reports.

Changing the approach to technical cooperation is likely to require revisiting how advice and analysis is funded and finding ways to prioritise longer-term relationship building over fly-in, fly-out standalone reports. MDBs should attract a wider range of expertise, while staff should be rewarded for the impact of their advice rather than the quality of their report writing.

MDBs face challenges in balancing the aims and requests of funders and clients, and in identifying exactly who they should be accountable to. There is a strong emphasis on rules-based accountability and ensuring that shareholder-approved standards and due processes are followed. Complying with rules is of course important, but accountability towards borrowers – through the delivery of successful projects and sound advice, and through responding to their policy needs– tends to be weaker.

MDBs could provide more information on their performance in terms of the long-term impact of their lending. They should commit to making more easily accessible the information about their lending practices as well as client surveys and administrative data with useful metrics (e.g. project approval times). Citizens could be far more engaged in monitoring and verifying outcomes and KPIs, especially in combination with big data, machine learning and AI. MDBs could also make better use of the information provided through their independent evaluation offices.

The question of how MDBs can step up to address global challenges has been dominated by concerns around high-level issues of mandates, increasing financial headroom and reviewing the concessionality of different lending instruments. While these are all important issues, they overlook the long-standing criticisms of MDBs that may be limiting demand from borrower clients.

This time of polycrisis calls not just for bigger banks, but for better banks. We must acknowledge more openly that the day-to-day operations of MDBs are not working as well as they should. MDBs are too slow, unresponsive and risk-averse. While the improvements outlined in this article may not be glamorous or lead to a fundamental (and unlikely) reimagination of the social contract within which these institutions operate, they would nonetheless represent some progress. Not only must MDBs improve their lending practices; they must also develop and share ideas that work for their clients.

Mark Miller is Director of Development and Public Finance Programme, Overseas Development Institute.

Linda Calabrese is Research Fellow, International Development Programme, Overseas Development Institute.

Ganeshan Wignaraja is Professorial Fellow for Economics & Trade at Gateway House and Senior Research Associate, International Development Programme, Overseas Development Institute.

Annalisa Prizzon is Principal Research Fellow, Development and Public Finance Programme, Overseas Development Institute.

This article was published by ODI.