The Indo-Pacific is the planet’s most strategically important and dynamic region. From the east coast of Africa to the west coast of the Americas, changes are taking place that are likely to shape the future for generations to come.

Drivers of strategic shifts in the Indo-Pacific

One of the most visible aspects of these shifts involves the massive military expansion and modernization of the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC), which now has the largest navy in the world.[1] Concern over Beijing’s intentions has driven a range of responses, including the signing of a series of bilateral defense, logistics and security agreements between countries in and engaged with the region,[2] including the AUKUS trilateral security partnership.[3]

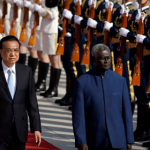

However, while the PRC is clearly augmenting its war fighting capabilities, its comprehensive national power approach,[4] combined with its utilization of unrestricted warfare[5] and its doctrine of civil-military fusion[6] suggests that its preferred battlefield is political warfare, where its strategy involves “winning without fighting.”[7] Indeed, many of Beijing’s strategic gains in the Indo-Pacific have been accomplished through means such as economic engagement via the Belt and Road Initiative.

Beijing’s preferred strategy is to engage a target country through goodwill (high level visits, scholarships, largess for decision makers, etc.), until the leaders of the country’s political and business sectors accept Chinese economic support. Ultimately, the process ends up with the country dependent on China.[8]

This dependency can be highly destabilizing, as decision-makers distort local economies and societies to suit the interests of their PRC patrons and, in turn, the PRC favors leaders with authoritarian tendencies who can deliver for Beijing.[9]

While it doesn’t always succeed, this strategy works often enough for some countries to slide quietly into Beijing’s sphere of influence without triggering any effective response, as was seen in 2019 when Solomon Islands and Kiribati both switched diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to China,[10] taking some in New Delhi, Washington, London and elsewhere by surprise. The same process is occurring in a range of other countries throughout the region and the world.[11]

While growing defense and intelligence relationships are a helpful response, especially to the military dimensions of the PRC’s expansion, countries need support that will enable them to defend themselves from Beijing’s political warfare so that they can thrive on their own terms. This is where India is indispensable.

India’s unique position in the Indo-Pacific

Many countries across the Indo-Pacific have economies and societies that are much more like India’s than western nations’ or China’s. The products and services of the U.S., Australia and Japan are often more expensive than the majority of the population can afford. This is why Chinese services and products can so easily take over markets, especially since China’s economic expansion is facilitated by the Chinese state.

Often overlooked until it’s too late is the fact that along with Chinese services and products comes the PRC way of doing business, which usually involves extracting most of the profit from the target country. For example, infrastructure contracts commonly go to Chinese companies using Chinese workers, and the Chinese products are sold through shops run by recently-arrived Chinese who send their profits back to China.

To achieve true human security and strategic independence that underpin a free and open Indo-Pacific, countries across the region need a third option, especially in foundational sectors, one that is more affordable and appropriate than what is offered by the west, and less exploitative and destabilizing than what is offered by China. In a wide range of key sectors – education, healthcare, telecommunications, transport, renewable energy, information technology, agriculture, and others – India is uniquely well placed to work with partners in the region to build the human and economic infrastructure required for security, prosperity and freedom in Indo-Pacific.

This is well understood in the region, where desire for more Indian engagement is often stated.[12] While India’s affordable and adaptable goods and services are an attraction, its social compatibility with countries is even more fundamental. For example, while the one-child policy has distorted demographics and destroyed the extended family in China, the extended family is critically important economically, socially, and even politically in countries across the region – including Indonesia, Thailand and the Philippines – as it is in India. For many in the Indo-Pacific, India just seems more familiar than China or western countries.

Why hasn’t India met the demand?

Reasons Indian engagement has been limited include its Ministry of External Affairs is overstretched, its business sector tends to be inward-looking and its government has made only limited efforts to promote Indian businesses abroad.

In addition, other countries, even India’s partners, sometimes see Indian engagement as competition. For example, low-cost pharmaceuticals from India, which could offer countries in the region an affordable and safe alternative to Chinese pharmaceuticals, can be perceived as a threat by western pharmaceutical lobbies.

This short-sightedness is reminiscent of the fable of the dog with a bone in his mouth that sees his reflection in a pool of water and opens his mouth to grab the “other dog’s” bone, in the process losing his. By grabbing at illusory or small economic “wins” in the Indo-Pacific, western countries risk losing much more as they can undermine regional human security contributing to destabilization, make offers from Beijing look more attractive, and gain a reputation as unreliable partners. At this point in history, larger strategic priorities must trump niche economic gains.

Building the model

India and its partners need a comprehensive and equitable cooperation model to achieve true regional security. A first step could be to focus on working initially with one geographic area where relatively small efforts can yield major results, and then expanding the model based on lessons learned.

One part of the Indo-Pacific where this could be quickly implemented is in the countries of Oceania. There are close to twenty independent countries in this vast strategic region roughly in a triangle between Hawaii, Japan and New Zealand. Many of the countries have small populations but control vast exclusive maritime economic zones. They also have votes in the United Nations.

This region is a priority target area for China, as seen by its recent moves in Solomon Islands and Kiribati. Having looked closely at the battle map of World War Two, Beijing knows controlling the islands is key to cutting the U.S. off from Asia, and isolating Australia and Japan. It is also a major nexus of undersea cables.[13] It has been successfully consolidating its position in the region through deft and concerted political warfare.

Concern over increasing Chinese influence in the area has resulted in a flurry of activity from India’s Quad partners, the U.S., Australia and Japan. Recently, Australia deployed troops to Solomon Islands, and Japan has announced it will be opening an embassy in Kiribati.

India’s unique offerings were brought to the fore when the Quad announced its vaccine initiative, built around India’s production capacity and highlighting outreach to the Pacific Islands. But there is much more to be done. Some examples are:

Environmental protection. Many countries in Oceania have ecologies that are similar to South India and India’s islands. Some of the effective and low-cost construction, anti-erosion, cyclone-proofing, rainwater harvesting, and other technologies and techniques it has developed in those areas would translate well to region. It would also dovetail well with mutual concerns about climate change.

Institution building. Most countries in Oceania are English speaking, or have English as a second language, and many have parliamentary and legal systems that are similar to India’s. Exchanges with legal experts and parliamentarians would build understanding and expertise, and could contribute to pushing back on China’s attempts to shape and control international rules and norms.

Medical, veterinary, aquaculture, dental training. Most countries in Oceania are understaffed in these areas and have similar concerns – including tropical illnesses and high diabetes rates – as India. Access to education in India is one option, but even better would be for India to set up educational facilities in the region.

Intelligence training and sharing. Currently most countries in the region have limited access to intelligence sharing, even though they are targets of serious organized-crime networks. They also often have to off-shore their forensic testing due to limited testing facilities. In many cases, Chinese organized crime – including gambling, money laundering, drugs, and prostitution – enters the countries of the Pacific along with PRC commercial and strategic interests. Cooperation in addressing this socially, and politically, destabilizing problem would be very helpful.

There are myriad other examples. The question is how to start the process, given the limitations. In this case, looking to see how China has done it may be helpful.

Rather than centralizing Oceania engagement in Beijing, where it could be lost in “noise” of the capital, the PRC largely delegates Oceania outreach to its coastal province of Guangdong. This was a smart move for several reasons. Success in Oceania became important for leaders in Guangdong, who wanted to prove their worth to their bosses in Beijing; the climate was similar; and it was easier to develop a dedicated network of Chinese businesspeople and academics in Guangdong who would build relationships over the long-term with people of the region.

Similarly, it might make sense for Tamil Nadu or Kerala to take the lead on outreach to the Pacific Islands. Ideally, a chamber of commerce-style organization could be set up to facilitate trade, maritime security training could be facilitated with India’s new Maritime Theatre Command[14] (and through that with the Quad), and think tanks and universities could take the lead on academic exchanges and possibly on setting up branches in the region (Guangdong has two research institutes dedicated to the Pacific islands[15]). This effort should be self-supporting; many leaders in the region wants reliable, viable and equitable trade more than they want drip-fed aid.

Many of the countries of the Pacific have very limited government budgets to facilitate activities like this, so a “Pacific House” could be established in New Delhi where representatives from Oceania can stay, enhance diplomatic coordination and move projects forward. Increased Indian representation in the Pacific islands also would be helpful.

Given the limited Indian diplomatic outreach in Oceania, it might make sense for key Government of India nodes to co-locate with partners. For example, Quad partner Japan is highly respected in Oceania, especially for its aid projects, but while it excels in infrastructure development (building hospitals, schools, etc.), it does less well with human infrastructure; while Japan built a hospital in Tonga, for instance, China ended up sending doctors to staff it. It would have been better for the people of Tonga, and for Japan, if the doctors been Indian or, even better, Tongans trained in India or at an Indian medical school set up in the region.

Japan’s excellence in hard infrastructure, combined with India’s strength in building human infrastructure, could benefit many in the region. Such partnerships could be facilitated by, for example, representatives from India’s world-leading development, trade, investment and technology research institute, Research and Information System for Developing Countries (RIS), who could co-locate at Japanese embassies in the region.

Bottom line: India, the Quad and Oceania

Oceania is on the front line of Chinese political warfare. It is a region that the PLA Navy must control if it is to have dominance in the Indo-Pacific. If it is not stopped there, Beijing’s ability to project power moves ever closer to the shores of India, Australia, Japan and the U.S.

Chinese advances have been made possible by the comprehensive nature of its engagement – in particular, its strategy of using economics as an entry point. But Beijing is destabilizing the region.[16] Local leaders know this and want options. Among the Quad countries, only India can give China a run for its money in affordable and appropriate economic engagement.

For a free, open and prosperous Indo-Pacific, India – supported, or at least not hindered, by its Quad partners – must play a bigger role in creating options for the countries of Oceania. It is truly indispensable for stability in the region, and beyond.

Cleo Paskal is Associate Fellow, Environment and Society Programme and Asia-Pacific Programme, Chatham House.

This paper has been published by Gateway House, with the support of the United States Embassy, New Delhi. Read the full compendium ‘India in the Indo-Pacific: Pursuing Prosperity and Security’ here.

The views and opinions expressed in this paper are solely those of the authors. The views expressed in the paper do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Embassy, New Delhi.

For interview requests with the authors, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2022 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References:

[1] https://media.defense.gov/2021/Nov/03/2002885874/-1/-1/0/2021-CMPR-FINAL.PDF?source=GovDelivery

[2] https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/beca-india-us-trade-agreements-rajnath-singh-mike-pompeo-6906637/

[3] https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/09/15/joint-leaders-statement-on-aukus/

[4] http://www.kiips.in/research/protection-from-chinas-comprehensive-national-power-requires-comprehensive-national-defence/

[5] https://www.c4i.org/unrestricted.pdf

[6] https://2017-2021.state.gov/military-civil-fusion/index.html

[7] https://www.usmcu.edu/Portals/218/Political%20Warfare_web.pdf

[8] https://csbaonline.org/uploads/documents/Winning_Without_Fighting_Annex_Final2.pdf

[9] https://www.sundayguardianlive.com/news/china-buys-foreign-politicians-case-study

[10] https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/solomon-islands-and-kiribati-switching-sides-isnt-just-about-taiwan/

[11] https://news.yahoo.com/only-one-china-nicaragua-declares-172701614.html

[12] https://www.chathamhouse.org/2021/03/indo-pacific-strategies-perceptions-and-partnerships/06-tonga-and-indo-pacific

[13] https://www.gatewayhouse.in/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Quad-Economy-and-Technology-Task-Force-Report_GH_2021.pdf

[14] https://www.financialexpress.com/defence/maritime-theatre-command-by-next-year-navy-chief/2381480/

[15] http://dpa.bellschool.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/publications/attachments/2020-02/dpa_in_brief_2020_2_zhang_final.pdf

[16] https://www.theaustralian.com.au/world/chinese-money-used-to-sway-mp-votes-for-solomon-islands-prime-minister-manasseh-sogavare/news-story/dd003f3f2b518c305ef10bf4c89f1b70