Denmark’s Social Democrats, led by incumbent prime minister Helle Thorning-Schmidt, won the largest share of votes (26%) and the largest number of seats (47 of 179) in the country’s June 18 parliamentary election.

As the popular narrative about these elections notes, Thorning-Schmidt and her party may have won the battle by equalling their best electoral performance in a decade, but they have lost the war.

That is because in this election, the extreme right wing Danish People’s Party (DPP) secured 21.1% of the votes and 37 seats, to become the second-largest party. It is now a part of the ruling coalition, led by the third-largest party Venstre, which got 19.5% votes and 34 seats.

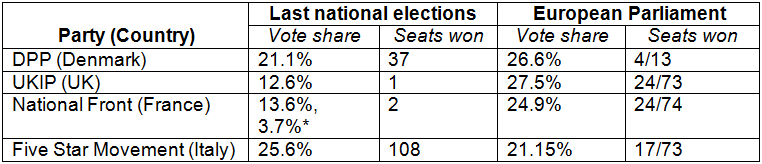

The right-wing parties are resurgent not only in Denmark, but also Finland and Norway, both of which also have right-wing coalition governments that comprise parties who champion anti-European Union (EU) and anti-immigration views on the continent. The same trend is evident beyond Scandinavia, where previously fringe parties have now become more prominent by tapping into those sentiments among sections of the electorate (See Table).

Performance of parties in national and European elections[i]

*Percentages refer to the first and second rounds of voting in the 2012 French Legislative election

The DPP, like the other formerly fringe parties, reflects a conflation of anti- EU and anti-immigration sentiment stemming from concerns about the free movement of labour within the EU, in particular from East to West Europe.

This is an entrenchment of an existing trend. While west European countries were apprehensive about immigrants from southern Europe and North Africa during the Cold War, the disintegration of Yugoslavia between 1990 and 1992 fostered a mood of anti-Slavic unease about the movement of labour from the former Yugoslav republics in Eastern Europe.

Now, this anti-immigration attitude is additionally imbued with Islamophobia. The first Muslim immigrants to arrive in Denmark were Kurds and Pakistanis, invited as “guest workers” in the 1960s.[1] Denmark was, as most of western Europe, arguably more accommodating of foreign cultures at the time, though the degree and intensity of integration demanded varied across the continent.

In the early 1990s, and around the time of the dissolution of Yugoslavia, Muslims accounted for a little over 1% of Denmark’s population.[2] In 2015, they make up the second largest religious community at over 4% of the country’s population.[3] This increase in 25 years has fed into the sense of alarm among a section of Danes, which is rooted in cultural differences as well as economic pressures.

A major grievance among the anti-immigration segment of Danish society is the growing allocation for social spending in the national budget. It is fundamentally in this sphere that anti-EU and anti-immigration sentiment conflates. Danes, like the citizens of many other European countries where GDP growth has slowed to a crawl, connect the absence of any signs of continuous growth to a perceived influx of “outsiders” who are misusing their welfare system. This has precipitated the right-wing backlash.

In Denmark, although the GDP increased from approximately $138 billion in 1990 to $336 billion in 2013,[4] the rate of growth in 2013 was -0.7%.[5] The country has one of the most comprehensive welfare systems and the fourth highest social spending (from 25% of GDP in 1990 to 30% in 2014)[6] among OECD countries, after France, Finland, and Belgium.

But linking this data solely to Muslim immigrants is specious. At the beginning of 2014, of all immigrants and their descendants, nearly a third were Scandinavian and German (while the rest were from predominantly Muslim Turkey, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Somalia, and South and West Asia). The total number of immigrants in Denmark constituted roughly 10.7% of the population[7] in 2014, but nearly double that number were receiving some sort of public benefits.[8] The argument about immigrants cornering budget allocations is clearly not supported by the data.

The emergence of louder and more rancorous anti-immigration voices across Europe, along with the political gains of the parties these voices represent, come at a time when the UN has revealed that the worldwide displacement of people is at an all-time high: there are nearly 60 million refugees in the world today.[9] At the end of 2014, the largest outflows of refugees were from Syria (nearly 4 million), Afghanistan (2.6 million), and Somalia (1.1 million).[10]

It is ironic that the more NATO countries—many of them also a part of the EU—intervene militarily in the Islamic world (stretching from North Africa to Afghanistan), many more thousands of people will flee their homes and seek refuge in unwelcoming Europe.

Fortress Europe needs to introspect, rather than blame the victims. But that will not happen while it pays the kind of political dividend that the DPP just reaped in Denmark.

Neelam Deo is Co-founder and Director, Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations; She has been the Indian Ambassador to Denmark and Ivory Coast; and former Consul General in New York.

Karan Pradhan is a Senior Researcher at Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2015 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited

References

[1] Rytter, Mikkel, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 37:2, Money or Education? Improvement Strategies Among Pakistani Families in Denmark, December 2010, p. 200, <http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2011.521356>

[2] Jensen, Tim, University of Southern Denmark, Odense: Denmark, Islam and Muslims in Denmark: An Introduction, 2007, p. 110, <http://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/ILUR/article/viewFile/ILUR0707550107A/25862>

[3] Denmark.DK, Religion in Denmark, <http://denmark.dk/en/society/religion/>

[4] World Bank, GDP per capita (Current US$), <http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD>

[5] World Bank, GDP Growth (annual %), <http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG/countries>

[6] OECD Stat Extracts, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Social Expenditure: Aggregated Data, <https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=SOCX_AGG>

[7] Denmark.DK, Facts and Statistics, <http://denmark.dk/en/quick-facts/facts/>

[8] Statistics Denmark, Ministry for Economic and Interior Affairs, Government of Denmark, AUK01: Persons receiving public benefits by region, type of benefits, sex and age, <http://www.statbank.dk/statbank5a/selectvarval/saveselections.asp>

[9] UNHCR News Release, Worldwide displacement hits all-time high as war and persecution increase, June 2015, <http://www.unhcr.org/558193896.html>

[10] Ibid