India, through the G20 presidency, intends to be remembered as the voice of the Global South at the heart of which is Africa. Most of the 54 countries of this continent are developing or least developed countries. To truly represent the South, it is essential to grasp the mood and changes in Africa, especially in its external partnerships. This will determine the contribution India can make to advance the African agenda. In this context, the outcome of the U.S.-Africa Leaders’ Summit needs a critical examination.

The second U.S.-Africa summit was held in Washington from December 13 to 15. The leaders of 49 countries and the chair of the African Union (AU) participated from Africa. U.S. President Joe Biden, who is yet to visit the continent, played gracious host, discussing the political, security, and economic cooperation with his guests. The leaders also deliberated on the ways to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 and future pandemics, respond to the climate crisis, promote food security and deepen diasporic ties. Mr. Biden declared that African voices, leadership and innovation are “all critical to addressing the most pressing global challenges” and realising the vision of a free, open, prosperous and secure world. The U.S. is “all in on Africa and all in with Africa,” he stressed.

Several important decisions were taken. First, the U.S. announced its support for the AU to join the G20 as a permanent member. Second, the U.S. said it “fully supports” reforming the UN Security Council (UNSC) to include permanent representation for Africa. The first assurance is implementable immediately, provided the U.S. and India overcome likely resistance from the ASEAN and European Union. But the second is vague since UNSC reform is still far into the future. Third, a promise for the president and the vice president to visit Africa next year was made. This will be a refreshing change as no U.S. president has been seen in Africa since 2015.

Summits with Africa are often judged by the quantum of funds external partners are willing to offer for economic development. The U.S. announced new investments and initiatives, including $21 billion to the International Monetary Fund to provide access to necessary financing for low-and middle-income countries, and $10 million for a pilot programme to boost the security capacity of its African partners. The administration indicated that it planned to invest $55 billion in Africa over the next three years, working closely with the Congress.

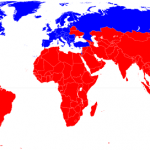

Nevertheless, the U.S.’s attempts to raise its profile in Africa remain episodic and faulting. China, on the other hand, has emerged as the largest trading partner and the fourth largest investor in the African continent, ahead of the U.S., through its steady diplomacy and extensive economic engagement. In 2021, while U.S.-Africa trade stood at $44.9 billion, China-Africa trade exchanges stood at $254 billion. The U.S. investment stock in Sub-Saharan Africa was $30.31 billion last year, compared with China’s total investment in Africa of $43.4 billion in 2020.

Here, the U.S. and other nations can take a cue from the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), established in October 2000. The FOCAC is composed of ministers and leaders of Africa and China who meet once in three years, alternately in Beijing and an African capital. The Chinese president participates in deliberations in person or digitally. China has a full-fledged inter-ministerial mechanism to ensure the timely implementation of FOCAC decisions. The last meeting, held in Dakar in 2021, expressed support for the Chinese agenda: One-China Principle, the Global Development Initiative, the Belt and Road Initiative, and the vision of “a community with a shared future.” It also applauded the decision by the 2018 FOCAC summit in Beijing to build “a China-Africa community” that strives for “win-win cooperation.” For years, the Chinese foreign minister begins his annual series of foreign visits by travelling to Africa. Whatever flaws there may be in China’s economic diplomacy in Africa — and there are many, its consistent attention to Africa contains a useful lesson.

Just before the Washington summit, Don Graves, the U.S. Deputy Commerce Secretary, noted that the U.S. had fallen behind as China surged ahead. His claim that the U.S. remains the “partner of choice” should be weighed against constant feedback received from African leaders that they do not want to choose. They want the U.S., China, and all other partners to work with them because Africa’s needs are huge.

India’s equity in Africa is older and richer than that of China and the U.S., but that should not be a source of complacency. India has striven hard, in the past two decades, to strengthen its political and economic partnership with Africa at the continental, regional and bilateral levels. The Modi government created a special momentum in arranging high-level exchanges and forging cooperation initiatives during the 2015-19 period.

Since then, COVID-19, the economic downturn, the war in Ukraine and border conflict with China may have contributed to a slowdown. This should be arrested quickly. The G20 presidency is India’s opportunity to ensure that the AU becomes a permanent member of this grouping and to reflect firmly Africa’s Agenda 2063 for development. India and the U.S. should work closer together in Africa. Finally, the fourth India-Africa Forum Summit should be held in early 2024, lest the third summit held in 2015 becomes a distant memory.

Rajiv Bhatia is Distinguished Fellow for Foreign Policy Studies, Gateway House, and a former ambassador.

A version of the article earlier appeared in The Hindu.