A controversy surrounding the World Food Prize highlights how the fault-lines of power struggles are no longer essentially between nations. Civil society organisations across the world are taking on both corporations and governments over what will actually secure our species’ food future.

Interestingly, both the World Food Prize and its counter, an activist initiative known as the Food Sovereignty Prize, are based in the U.S.. This year’s World Food Prize is being shared by three bio-technology scientists for their work on genetically modified foods – two of them senior executives of agri-industry giants Monsanto and Syngenta. The Food Sovereignty Prize has gone to a peasant organisation in Haiti with honorable mentions to a farmers group in Spain, one in Mali and the Tamil Nadu Women’s Collective in India.

The World Food Prize, which has sometimes been referred to as the Nobel for agriculture, was founded in 1987. It was instituted by the Nobel Laureate Dr. Norman E. Borlaug, commonly known as the father of the ‘Green Revolution’, and General Foods Corporation. By contrast the Food Sovereignty Prize is the work of an activist network called the U.S. Food Sovereignty Alliance. Members of this alliance include a wide range of groups working to end poverty, rebuild local food economies, and assert democratic control over the food system.

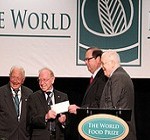

Recipients of this year’s World Food Prize will be honored on 17th October at a glittering ceremony in Des Moines, U.S., where over 800 people from more than 75 countries are expected to attend. Members of a campaign known as “Occupy World Food Prize” are expected to hold protests outside. This tableau easily lends itself to a one-dimensional narrative. Proponents of genetically modified organisms (GMO) dismiss the protesters as being anti-science and anti-growth. The protesters counter that by condemning GMOs as a Frankenstein technology than endangers both human health and bio-diversity. Both sides accuse each other of endangering future food security.

Over the last decade this polarisation has manifest itself in most countries, including India. There is an urgent need to at least look beyond, if not overcome, this stalemate. There are two distinct dimensions of this dispute. One pertains to what is good science and how we might therefore make choices about technology. The other has to do with the clash between command-and-control business models versus more equitable models that foster economic democracy. Interestingly, Dr. Borlaug is best known for integrating various streams of agricultural research into viable technologies. Today, a plurality of approaches to agricultural technology is the main bone of contention. The “GMO war”, which tends to generate the loudest headlines, is just one part of a much larger and increasingly complicated global struggle.

In this context the prestige of the World Food Prize foundation has been marred by its close association with both big agri-business and the U.S. government. Major corporations, including Monsanto, are funders of the Prize. For the last ten years the ceremony at which the winners of the World Food Prize are announced has been hosted by the U.S. State Department.There is no dispute about the need to accelerate responsible agriculture and lift millions of people out of poverty. But how is this laudable goal to be met?

This is why the World Bank and the Food and Agriculture Organization in 2002 initiated the International Assessment on Agricultural Knowledge, Science and Technologies for Development (IAASTD) as a multi-stakeholder initiative involving scientists, government officials and private sector representatives from 110 countries. The IAASTD report, released in April 2008, concluded that current models of industrial agriculture cannot ensure future food security. While the report did not reject GMOs it clearly concluded that there is no basis for saying that future food security depends on GMOs. The U.S., Canada and Australia were conspicuous among countries that refused to be signatories to the final report. However, United Kingdom and France joined numerous developing nations in adopting the IAASTD report.

This means that all claims about GMOs – for or against – need closer scrutiny. Anyone who suggests that science has settled the matter is not quite telling the truth. It is, however, concerns about economic democracy that drive much of the opposition to the agri-business tilt of the World Food Prize. Entities like the U.S. Food Sovereignty Alliance are essentially opposed to business models that are privatizing seeds and promoting chemical-dependent agriculture that becomes more and more capital intensive. In particular they are opposed to patent regimes that ensure that more and more of the surplus generated benefits a handful of companies. These fears have grown in intensity following the U.S. Supreme Court judgment, earlier this year, in the case of Monsanto vs. Bowman. In a unanimous ruling the Court said that farmers cannot replant harvest from Monsanto’s patented genetically altered soybeans without paying the company a fee. Though the legal implications of the ruling are said to be limited – it has nevertheless strengthened the case of those who oppose corporate control of agriculture.

It is not clear how this power struggle between big agri-business and other models of agriculture will be resolved. But the events in Des Moines this week may have a silver lining. Ghana’s Cardinal Peter Turkson, who is also president of the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, is invited to speak at the World Food Prize ceremony. He also plans to appear at an event hosted by the Occupy the World Food Prize campaign. Turkson has earlier described economic dependence on agribusiness as a new form of slavery because “ …if poor farmers have to buy every seed that they plant then it limits their ability and freedom to plant and grow food.”

There is need for many more leaders who, like Turkson, are keen to “listen to all and see how we can make a very sympathetic presentation of the issue that would be acceptable to both sides.”

Rajni Bakshi is the Gandhi Peace Fellow at Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations.

This article was originally written by Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations, exclusively for Livemint, here. You can find more exclusive features here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact Rajeshwari Krishnamurthy at krishnamurthy.rajeshwari@gatewayhouse.in or 022 22023371.