The dramatic withdrawal of the U.S. from Afghanistan in August 2021, enabling the Taliban’s takeover of the country, has changed the geopolitics of Asia forever.

The U.S. spent $2.3 trillion in 20 years on security and defence in Afghanistan, and left behind an estimated $85 billion in military assets.

But how did the Taliban fund its own resurgence after 2001? The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) estimates the Taliban’s annual revenue to be between $300 million and $1.5 billion[1].

The group drew financial support from various actors, within and outside the state, and research by Gateway House shows four major sources of funding for the Taliban – the revival of opium cultivation, and its global sales; mining; extortion and illegal taxation; donations.

Opium Economy

A major source of funding for the Taliban was opium, and the economic activity centred around it, including cultivation, production and smuggling of the product for lucrative foreign markets.

Following the American invasion in 2001, the opium economy was not a priority for the U.S.-installed Karzai regime. The Taliban, however, had reappeared in the opium economy after 2001. Using a network that included warlords, local elites and traders, the Taliban were able to create and enforce an informal taxation system for the opium economy in parts of Afghanistan. Without a ready formal or informal credit system in place, citizens, shopkeepers, smugglers and low-level traders participated in this system[2]. In Helmand, smugglers provided credit for farmers by paying for half of the value of the product in advance, and credit for fertilisers[3].

The focus moved to counter-narcotics efforts in 2006 with the Afghanistan Compact, where the Afghan government and the international community agreed ‘to strengthen their partnership to improve the lives of Afghan people’[4]. Efforts were made to replace or eradicate poppy in Afghan fields. Manual eradication was carried out by the U.S. trained Afghanistan Eradication Force, international efforts were made to replace poppy with roses and other commercially profitable crops and in 2016, the U.S. launched an aerial strike campaign, targeting labs producing opium.

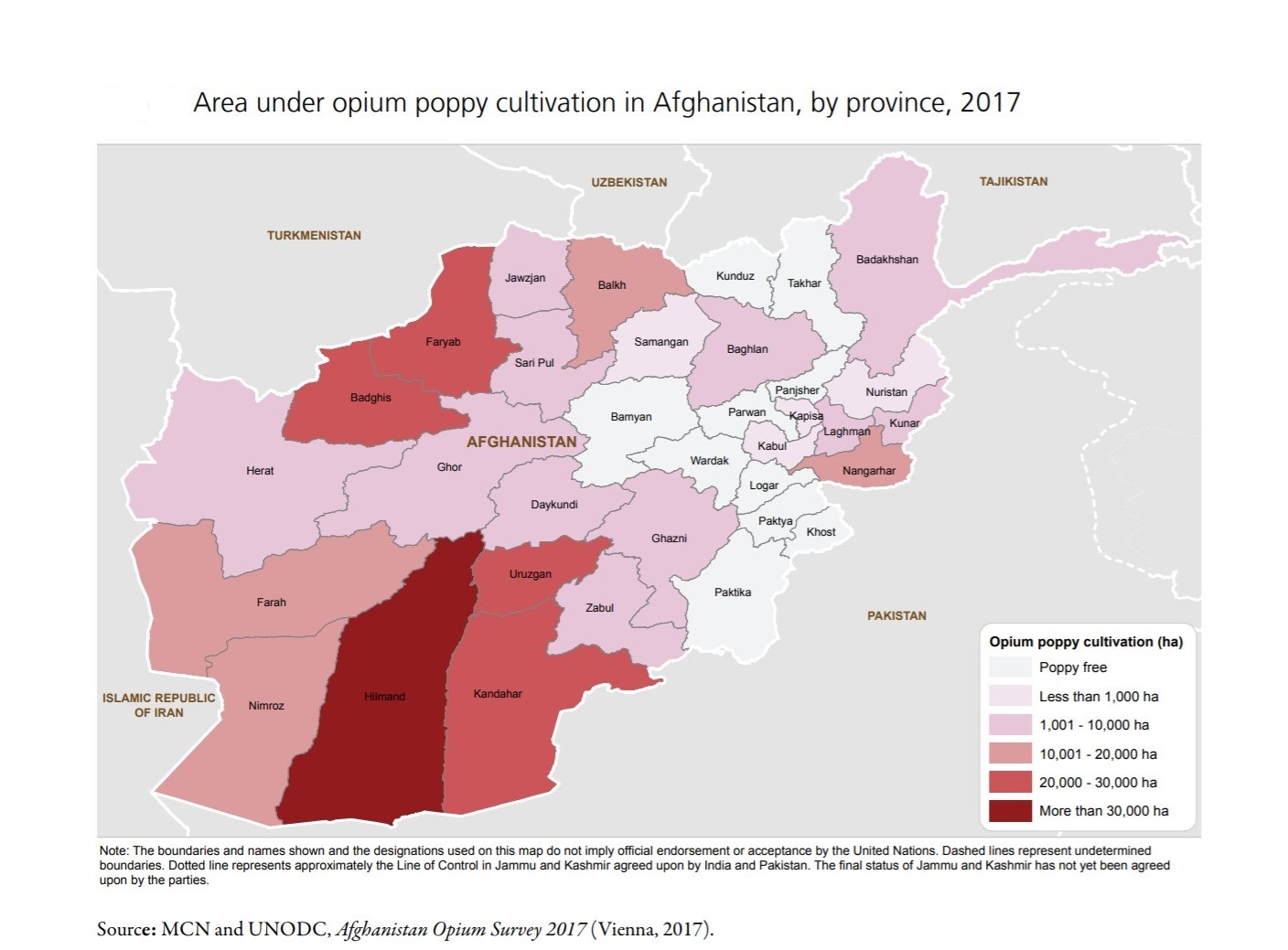

It failed to have any long lasting impact and land under opium cultivation expanded to 224,000 hectares in 2020, 37% higher than in 2019. Afghanistan now accounts for 83% of global supply of opium[5]. A study by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) estimates the opium economy in 2019 to be between 6% and 11% of Afghanistan’s GDP[6].

Cultivators are taxed 6% to 10% on the farm-gate value of the opium largely in the Southern and Western provinces, where most of the production takes place[7]. The tax alone amounts to at least $60 million, and up to $113 million in revenue pre-pandemic [8]. Labs, concentrated in obscure areas of Helmand and Farah which produce heroin are taxed between 1% and 3% and also make payments as “gifts” and “charity” to the local Taliban commanders. These are irregular payments dependent on the circumstances of the economy as well as the lab owner[9].

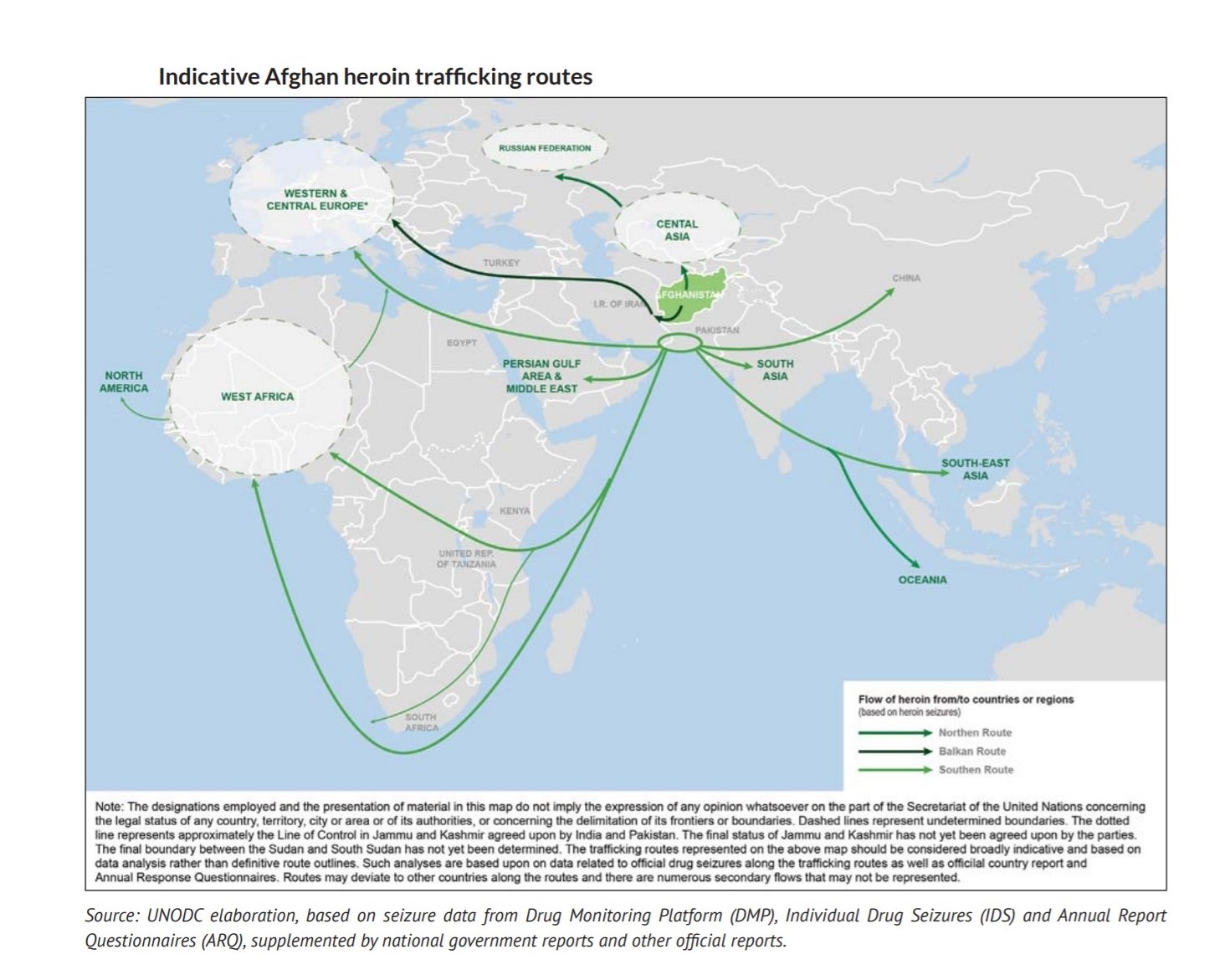

The finished product is then smuggled across South Asia through the ‘Southern Route’ which runs through Pakistan, and north across Europe through the ‘Balkan Route’ which links Europe and Afghanistan through Iran, Turkey and the Balkan states[10]. In India, states on the West coast and those bordering Pakistan are a major source of heroin trafficking[11]. In 2021, $2.7 billion worth of heroin which originated in Afghanistan was busted at the Mundra Port in Gujarat[12].

Mining

Afghanistan has an estimated $1 trillion worth of minerals, from iron and gold to the much-sought-after rare earth minerals, which are essential for high tech products like phones, computers, military aircraft, and electric vehicles. The Taliban understands the value of these resources, and over the course of its insurgency it has become a stakeholder in the industry[13].

Raw materials like onyx marble, rubies from Gharan, and gold from Takhar, provide significant revenues. According to a 2014 report by the UNSC, the Taliban exercised control over 25-30 onyx marble mines in Helmand province alone. This mining operation, larger than Helmand’s legal mining sector, is located close to the Pakistani border for access to international markets and generates over $10 million in annual revenues[14].

While exact data on mining operations and revenues is limited, estimates put the Taliban’s net profit from the mining industry at $464 million[15]. This also includes earnings of $1 million through extortion of mine operators in the lapis lazuli mines in Badakhshan province[16] and $16 million from the ruby mines in Kabul in exchange for ‘security’.[17]

Extortion and Taxation of Legal Goods

The Taliban uses tax and extortion in equal measure in the trade of legal goods like food grains and fuels and tolls for the use of highways and roads[18]. The control of important crossings like Spin Boldak and Zaranj on the border with Pakistan and Iran, respectively, are sources of income.

In provinces and districts under Taliban control, the group took over the traditional functions of government. The Taliban was able to extract revenue by permitting the construction of public infrastructure, taxing private contractors and telecom companies[19] and collecting taxes like ushr and zakat, usually charged at 10% of income[20].

In contrast, a closer look at Nimroz, which was largely controlled by the national government helps unpack the revenue-collecting activities of the group in areas not under direct Taliban control[21]. In Nimroz, the transit of goods and fuel from neighbouring Iran generated $40.9 million in revenue in 2020. This was collected along the stretch of roads controlled by the Taliban. The U.S. government’s oversight agency SIGAR’s 2016 report also revealed how the Taliban was exploiting the U.S. military’s logistics networks by demanding money for safe passage through contested areas[22]. Since 2018, this revenue collection by the Taliban has become more organised with the introduction of paperwork and checkpoints[23] to prevent vehicles from being taxed multiple times.

Charity and Donations

Foreign donations are a major source of income. According to Afghanistan’s Center for Research and Policy Studies, the Taliban received between $150 million to $200 million annually [24] from private citizens and charitable foundations in the Gulf countries. Nearly $60 million was funnelled through the Haqqani Network annually.

The donations are sent to Afghanistan and Pakistan in small sums of cash through sometimes unsuspecting couriers. The diaspora network is mobilised to send money through returning pilgrims and businessmen from the Gulf[25]. And members of the Taliban themselves travel regularly to Saudi Arabia and the UAE to collect millions in donations. Money is also laundered through businesses.

While the Taliban accumulated significant funds during its insurgency, the need for resources is significantly greater since it has taken over Afghanistan. Domestic sources have funded Afghanistan’s operating budget in the past, which pays the salaries for government employees, but the development and military budget was largely funded by aid from the US. The Taliban now needs to explore other ways of financing the state.

Meanwhile, ordinary Afghans are the worst hit. Poverty levels in Afghanistan have risen sharply since the Taliban takeover. Foreign funds and development aid is now restricted and the banking system, which has set limits on withdrawals on deposits, is on the verge of collapse[26]. Afghanistan’s financial future remains uncertain.

Saeeduddin Faridi is Researcher, Gateway House.

Subodh Singh is Research Intern, Gateway House.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in

© Copyright 2022 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorised copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References:

[1] https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/s_2020_415_e.pdf

[2] Jonathan Goodhand, “From holy war to opium war? A case study of the opium economy in North East Afghanistan.” Central Asian Survey. Vol. no. 2. 2000, pp .265–280.

[3] 2014 UNSC Report

[4] https://www.nato.int/isaf/docu/epub/pdf/afghanistan_compact.pdf

[5] https://www.unodc.org/res/wdr2021/field/WDR21_Booklet_3.pdf

[6] https://www.unodc.org/documents/crop-monitoring/Afghanistan/20210217_report_with_cover_for_web_small.pdf

[7] UNODC/Government of Afghanistan Ministry of Counter Narcotics (2008). Afghanistan Opium Survey 2008, Report, November

[8] https://www.unodc.org/documents/crop-monitoring/Afghanistan/20210217_report_with_cover_for_web_small.pdf

[9] https://www.lse.ac.uk/united-states/Assets/Documents/mansfield-april-update.pdf

[10] https://www.incb.org/documents/Publications/AnnualReports/AR2019/Annual_Report_Chapters/AR2019_Chapter_III_Asia.pdf

[11] https://narcoticsindia.nic.in/Publication/2018.pdf

[12] https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/ahmedabad/heroin-seized-at-mundra-port-weighs-3000-kg-worth-rs-21000-cr-dri-7524500/

[13] Peters, Stephen G., Stephen D. Ludington, Greta J. Orris, David M. Sutphin, James D. Bliss, James J. Rytuba, and W. J. Bawiec. “Preliminary non-fuel mineral resource assessment of Afghanistan 2007.” US geological survey open-file report 1214 (2007).

[14] https://undocs.org/en/S/2014/402

[15] https://www.undocs.org/pdf?symbol=en/S/2021/486

[16] https://undocs.org/en/S/2015/79

[17] https://undocs.org/en/S/2015/79

[18] Militia Order in Afghanistan: Guardians or Gangsters? M. Dearing

[19] https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/2020-04/20200430-sr_465-_service_delivery_in_taliban_influenced_areas_of_afghanistan-sr.pdf

[20] https://www.unodc.org/documents/crop-monitoring/Afghanistan/20210217_report_with_cover_for_web_small.pdf

[21] https://l4p.odi.org/assets/images/L4P-Nimroz-study_main-report-13.08.21.pdf

[22] https://www.oversight.gov/sites/default/files/oig-reports/SIGAR-16-58-LL.pdf

[23] https://l4p.odi.org/assets/images/L4P-Nimroz-study_main-report-13.08.21.pdf

[24] https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=124821049

[25] https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/s_2019_481.pdf

[26] https://www.af.undp.org/content/afghanistan/en/home/library/knowledge-products/Policy-brief-banking-crisis.html