How does governance affect economic outcomes? Governance is a concept that impinges on our lives every day in a thousand myriad ways. How am I treated when I go to the tax collection agency? Can I cast my vote without interference? How long did it take for the government to build that new road linking my village to the larger market town where I sell my vegetables? If the government decides to change its agricultural support policies, how do my views get incorporated into the new policies? How many agencies do I have to visit and how many different forms do I have to fill out when I want to start a new tech-oriented business?

These and other similar issues are summarised under the general concept of “governance”. To quantify and measure different aspects of governance, the World Bank created six different indicators, namely, voice and accountability, political stability and absence of violence/terrorism, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law and control of corruption.[1]

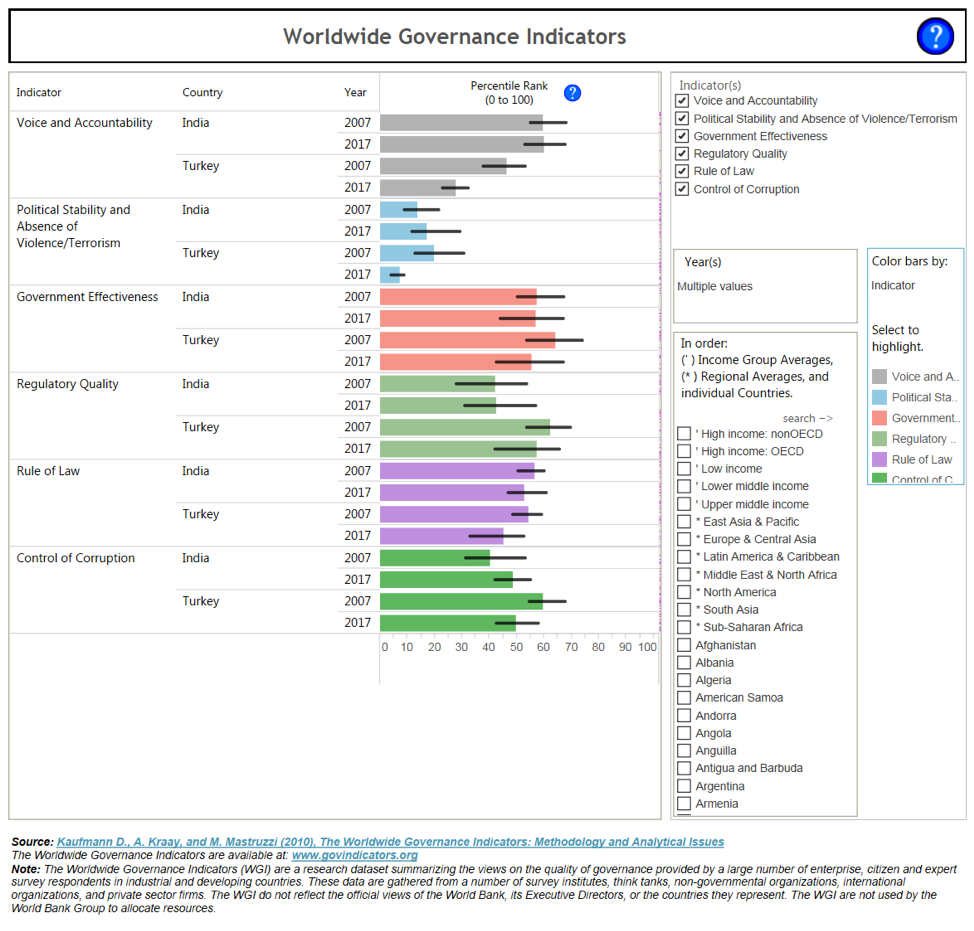

The following graph gives an overall overview of India’s governance indicators, compared to those for Turkey’s for the years 2007 and 2017.[2] Interestingly, we observe that India scores better than Turkey in indicators such as “voice and accountability” and “the rule of law”, especially in the more recent period. However, where Turkey has shown improvement is in areas such as “government effectiveness”, “regulatory quality”, and “control of corruption”, though there has been a regression in this last dimension in 2017 relative to 2007.

The recent literature on growth has emphasised the importance of better governance for long-term economic growth;[3] Acemoglu and Robinson in their widely acclaimed book,Why Nations Fail,[4] make a distinction between the role of extractive and inclusive political institutions in fostering economic development and argue further that it is dispersed political power, as witnessed in democracies, that will lead to long-term economic growth.

However, academics[5] note the intriguing fact that India – and China too – are outliers in terms of the cross-country relationship between a democracy index and GDP per capita. India remains too underdeveloped given the quality of its political institutions while China has become rich, but not democratic. As the analysis above reveals, the quality of India’s political institutions, measured in terms of indicators such as“voice and accountability” and “the rule of law”, exceeds those of a country like Turkey’s, which had around $10,000 GDP per capita in 2017 compared to slightly less than $2,000 for India. Hence, simply extrapolating a simple relationship between governance and economic growth may fail to capture the experience of some of the most important developing countries like India (or China, but in opposite ways).

One approach is to argue that developing countries must enhance their basic social infrastructure, such as well-functioning legal structures, regulatory frameworks, even the established sets of democratic norms, and societal conduct to launch their growth processes. An alternative argument: that growth itself will promote better governance as more developed societies will demand better protections for their wealth.

Some recently emerging literature recognises there may exist an alternative approach to this apparent dilemma, making the case for a more pragmatic reading of the relationship between governance and growth. Specifically, developing countries may “repurpose” their existing practices and institutions to spark growth as opposed to developing a full set of political and economic institutions as the precursor to such growth.[6] The primary examples the author cites are from China, which started with almost none of the practices and institutions of a free-functioning market economy that promote economic growth. Growth in China’s coastal cities – the initial impetus for its growth – was not propelled by first “establishing private property rights, eradicating corruption, and hiring technocrats”. Instead party cadres and civil servants were dispatched to recruit investors using their personal relations and officials received a personal cut. As markets took off, the quality of investment over its quantity began to dominate and formal property rights were instituted to protect the new wealth.

The development of Nollywood in Nigeria went from piracy in the film industry to professionalism and intellectual property rights protections. Even the U.S. economy followed a similar pattern, where financing of infrastructure projects in the 19thcentury went from government guarantees for privately-funded, non-transparent, risky projects to tax-based public financing, based on uniform rules.[7]

In its World Development Report 2017, the World Bank explicitly recognises the fact that instituting proper governance structures in many developing economy contexts is fraught with difficulties. Specifically, it asks “Why are carefully designed, sensible policies too often not adopted or implemented? When they are, why do they often fail to generate development outcomes such as security, growth, and equity? And why do some bad policies endure?” The Report argues that such policies do not take place in a vacuum. Rather “they take place in complex political and social settings, in which individuals and groups with unequal powerinteract withinchanging rulesas they pursueconflicting interests”[emphasis added].[8] In other words, the starting point for any changes in developing economies is very uneven, lacking basic institutions, the functioning coalitions and even mindsets necessary to bring about the necessary changes.

How does this approach translate into the Indian experience? In a discussion[9] of various models of political economy to understand the trajectory of India’s institutional and economic development, one academic has argued that the notion of a “developmental state”, used to characterise East Asian growth – or the extractive-inclusive political institutions binary earlier cited – may not be useful in understanding the nature of development in a vast and heterogeneous country like India. Instead, he finds more applicable theories that are based on societal groups and organisations and their role in explaining the distribution of power that ultimately shapes economic outcomes.[10]

Focusing on the issues facing India’s newly elected government in terms of governance, the same author points out that agriculture is one of the areas of the economy where there has been the least progress in determining how productive activities are governed. In a recent provocative article, Kripalani[11] argues that the political success and support of Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India and President Recep Tayyip Erdogan of Turkey owe much to the grounds-up reforms and initiatives of governments at both local and national levels to improve the basic living conditions of shanty-town dwellers, the rural poor and the urban lower classes.

So to return to some of the basic questions raised at the beginning: Were governments successful in building the road connecting the village to the market town? Have they put in place productivity-enhancing measures for farmers who may face reductions in non-market forms of support such as direct income supports? Have they instituted e-governmentto facilitate even those with modest education to access government services and facilities? Such grounds-up initiatives may ultimately determine whether countries like India and Turkey succeed in improving their governance structures at the same time as they enter a trajectory of sustainable growth.

Sumru Altug is Professor and Chair at the Department of Economics, the American University of Beirut, Her research interests are in the areas of dynamic macroeconomic analysis, business cycles, and structural econometrics.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in or 022 22023371.

© Copyright 2019 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References

[1]Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A. and Matruzzi, M. (2010). The Worldwide Governance Indicators: Methodology and Analytical Issues, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 5430

[2]This graph shows the percentile rank of the country on each governance indicator, which indicates the percentage of countries worldwide that rate below the selected country. Higher values indicate better governance. Percentile ranks have been adjusted to account for changes over time in the set of countries covered by the governance indicators. The statistically likely range of the governance indicator is shown as a thin black line. For instance, a bar of length 75% with the thin black lines extending from 60% to 85% has the following interpretation: an estimated 75 of the countries rate worse and an estimated 25% of the countries rate better than the country of choice.

[3]Clague, C., Keefer, P., Knack, S. and Olson, M. (1997). “Democracy, Autocracy and the Institutions Supportive of Economic Growth,” in Clague, C. ed. Institutions and Economic Development: Growth and Governance in Less-Developed and Post-Socialist Countries, John Hopkins University Press; Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A. and Zoido-Lobaton, P. (1999). “Governance Matters”, Policy Research WP Series, The World Bank; Hall, R.E. and Jones, C.I. (1999). “Why Do Some Countries Produce So Much More Output Per Worker Than Others?” The Quarterly Journal of Economics114, 83-116; and Rodrik, Subramanian and Trebbi (2004)..

[4]Acemoglu, D. and J. Robinson (2012). Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty, London: Profile Books

[5]Subramanian, A. (2013). “Which Nations Failed? Business Standard, January 21, https://www.business-standard.com/article/opinion/arvind-subramanian-which-nations-failed-112111300077_1.html.

[6]https://blogs.worldbank.org/governance/which-comes-first-good-governance-or-economic-growth-spoiler-it-s-neither

[7]Eichengreen, B. (1995). “Financing Infrastructure in Developing Countries: Lessons from the Railway Age”, The World Bank Research Observer 1(1), 75-91

[8]World Bank (2017). World Development Report 2017: Governance and the Law. Washington, DC: World Bank. doi:10.1596/978-1-4648-0950-7.

[9]Singh, N. (2019). “Theories of Governance and Economic Development: How Does India’s Experience Fit?” Munich Personal RePEc Archive https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/91049/1/MPRA_paper_91049.pdf

[10]“Governance Challenge for India,” July 3, Financial Express. https://www.financialexpress.com/opinion/governance-challenge-for-india/1626625/

[11]“Elections 2019: Making India Middle Class” Gateway House, May 21, https://www.gatewayhouse.in/india-elections-2019/