A dissonance separates China and India on Tibet and on the border dispute. India considers the border, especially in the east, as a matter of nationalist pride, but it views Tibet from a strategic angle. For China, the border is a strategic issue, while Tibet is integral to Chinese nationalism. China has a limited understanding of how important the border has become in Indian nationalist imagination. India in turn fails to appreciate Chinese sensitivities on Tibet. This dissonance is at the core of the bilateral dispute.

In the Western sector of Aksai Chin, India accuses China of occupation. In the Eastern Sector, China considers Arunachal Pradesh as India-occupied ‘Southern Tibet’. Various other factors have entrenched the dispute – the un-demarcated boundary, a rugged terrain where logical lines are difficult to draw, the legacy of the 1962 border war which humiliated India, security calculations, geopolitical actors, and bureaucratic interests.

But the most important factor is the transformation of the British-drawn India-Tibet border into the India-China border due to the Chinese occupation of Tibet from the 1950s. China and India have not yet fully grasped that Tibet and Tibetans are at the heart of the border dispute. Beijing and New Delhi are negotiating for territories that were historically neither Chinese nor Indian, but under various kinds of Tibetan control. The efforts of both countries to compete or try to make deals without concern for the people over whose lands border lines are drawn, have so far failed.

Jawaharlal Nehru’s India inherited the British policy of rebuffing Tibetan protests and quietly but firmly occupying territories in the North East Frontier Agency or NEFA (now Arunachal Pradesh) because Tibet handed them over to India during a secret Anglo-Tibetan agreement in March 1914 at the Simla conference. Tibet gifted India a significant chunk of its territory because the British promised support and friendship against China.

Post-colonial India continued to occupy NEFA, including Tawang in 1951, but reneged on the quid pro quo aspect of the deal and did nothing to help the Tibetans when the People’s Republic of China (PRC) took control of Tibet. In the Eastern sector, China inherited the disquiet of the Tibetan state with the Indian occupation of NEFA, especially Tawang. In the Western sector, things were even more vague in the absence of any survey or discussion, let alone a definition of the border.

Nehru sought to balance India’s border security, friendship with China, and empathy for Tibetans. But he failed to achieve any of the three goals. When a popular revolt forced the Tibetan spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama, to flee Tibet in 1959 and seek refuge in India, Nehru had no option but to give him asylum.

Instead of acknowledging the popularity of the indigenous revolt, the Communist Party leadership in Beijing saw it as the handiwork of Tibetan reactionaries and foreign imperialists tacitly supported by the bourgeois nationalists of India. The 1962 war was a result of Beijing’s desire to punish India for its “forward policy” in the border regions, and to remind India that its friendship was not essential for China to stabilise Tibet. But by pushing India to be more accommodative with the Tibetans, Beijing helped India to consolidate its legitimacy over the border regions.

Before 1951, Tibet itself acted as buffer against hostile powers; today the Tibetan diaspora in India acts as a bulwark against Chinese power. The fact that the Dalai Lama, and now the Karmapa, reside in India offers a strategic buffer to India against Chinese influence in the Himalayas that no degree of militarization can bring. How India recognises, respects and uses this diaspora will affect its position in the Himalayan region in a fundamental manner in decades to come.

The leadership transition in China is unlikely to have a significant impact on Chinese policy toward Tibet. The only difference is the absence of strident propaganda against the Dalai Lama and more polished public diplomacy campaigns to demonise him and project the Tibetan issue as unimportant. A recent high-level personnel change within the United Front Work Department, that oversees ethnic minority issues including Tibet, is unlikely to lead to a moderation of official attitudes toward Tibetans.

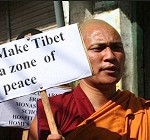

The mass protests in Tibet in 2008, followed by the ongoing upsurge in self-immolations by Tibetans, indicate the increased frustration amongst Tibetans and their fear that the Dalai Lama may never return to Tibet. This radicalisation shows that anti-colonial sentiments, rather than external influences, shape how Tibetans assert their political identity. China knows there is nothing India or any other country can do to prevent this type of protest. So far, it remains unwilling to ameliorate conditions in Tibet, where sections of Tibetans are unsuccessfully campaigning to retain their cultural and religious autonomy, or even offer hope by restarting negotiations with the Dalai Lama.

India too has limited control over how the situation will unfold in the Tibetan plateau after the leadership of the fourteenth Dalai Lama. All India can do is give space to Tibetans to chart their future in exile.

If the Chinese adopt the same approach over the succession of the Dalai Lama, as they did over the Panchen Lama – the second-highest religious figure in Tibet after the Dalai Lama – leading to two competing candidates and two Dalai Lamas, one in exile and one propped by Beijing, it will end all hope of a future dialogue between Beijing and the Tibetans, and will further radicalise the Tibetan movement.

China may avoid finding its own Dalai Lama but withhold recognition of the one discovered by Tibetans in exiles, and use granting recognition as a bargaining chip in future Sino-Tibetan negotiations. Any effort by India to try to influence the recognition process would be detrimental to the Tibetan struggle and India’s reputation.

The Tawang tract, where Mons are the dominant Tibetanised ethnic group, is one possible location where the next reincarnation of the Dalai Lama may be discovered. Tawang was also the birthplace of the Sixth Dalai Lama a few centuries ago. However, the Chinese assertion over Tawang in recent years is related more to the dynamics of Sino-Indian border negotiations, where the emphasis has shifted to sector-by-sector discussion to maximise claims in each sector.

What are the policy options for India? India cannot retract its recognition of Tibet as part of China’s sovereignty. But India should recognise the importance of Tibetans for India’s security. Security in the Himalayan borderlands does not come only from only a military build-up in which India cannot surpass China, or new border infrastructure, but also from the pro-India sentiments of its inhabitants. That pro-India sentiment arises from the significance of India for Tibetans. India must closely study the uncertainties of the post-Dalai Lama scenario while continuing to support and provide hospitable space to all Tibetan Buddhist leaders.

The role of the Karmapa, the third-highest religious leader in Tibetan Buddhism and the highest figure in exile after the Dalai Lama, is crucial. He is the only Tibetan figure who can carry on the Dalai Lama’s legacy of compassion, non-denominational Buddhism, and the message that the Tibet issue means more than the integrity of a nation. The Karamapa can act as a soft power source for India while the Fifteenth Dalai Lama is discovered. But if the Indian security establishment refuses to give him the space needed to grow in stature, India could lose the buffer that Tibetan religious exiles form against Chinese power in the region.

On the border, the only possible solution is to accept the status quo, something akin to what Zhou Enlai proposed in 1960. But if India could not accept it then, how will it accept it today? As for China, as it becomes a global power and faces major conflicts over its maritime boundaries, it has to decide if it wants to have a perpetually suspicious India to its south. China’s perception of closer Indo-U.S. relations will play an important role here.

The border dispute may remain unresolved in the near future. But both countries have to be more concerned about improving, through pro-people development, the lives of Tibetans in China and Tibetan refugees, as well as Indians in Ladakh, Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh who are ethnically and religiously part of the Tibetan cultural world. Only upgrading military infrastructure will not work. The future course of Sino-Tibetan relations will affect Sino-Indian relations. India should be proactive, not reactive, in maintaining a dynamic Tibetan diaspora – India’s real security guarantee in the Himalayan border regions.

Dr Dibyesh Anand is Associate Professor of International Relations at Westminster University in London and author of Tibet: A victim of geopolitics, and a forthcoming book on the China-India border dispute.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2013 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.