When Nelson Mandela stepped across the threshold of Victor Verster prison in South Africa in 1990, where he spent the last three years of his 27 years of incarceration, he once again bolstered struggles for respect and justice across the world.

On a chilly winter night in Jaipur, we got our first glimpse of Mandela stepping out to freedom. Watching the live telecast was simultaneously a celebration, a moment of solidarity, and a source of solace. We felt part of that crowd in another hemisphere, under a sweltering summer sun, waiting outside the prison cheering what was more than just Mandela’s victory.

Whatever songs the South Africans may have been singing on that day, my friends and I hummed Sahir Ludhanvi’s ode to the longing for a new dawn “woh subha kabhi to ayegi” – as we watched a beaming Mandela walk gracefully down the road, both arms lifted victoriously in the air.

It was not just the defeat of apartheid that brought the tears of joy. It was also the victory of tenacity, of courage against all odds, and above all the determination to keep a dream alive even when it seems impossible to realise.

By 1990, Mandela had come to symbolise all this and inspire protagonists of a wide variety of struggles in India – from people fighting to save their habitats from submergence by dams on the Narmada river, to people trying to stem the tide of communal hatred.

Many of us who gathered that evening to watch Mandela walk free were part of an informal group of activists. We were trying to undo the damage of a campaign by Hindu fundamentalist organisations, which was creating tensions between Hindus and Muslims in communities that had otherwise lived peacefully together.

Like millions across the world, we experienced the end of apartheid as a boost for all struggles against racial or identity-based prejudice. Over the next few years, as communal tensions rose to a fever pitch in many parts of India, leading to horrific violence in 1992-93, it was easy to despair. Often, our efforts to foster a culture of respect for all seemed desperately inadequate. Those breeding hatred seemed to win over more hearts and minds than we ever imagined possible.

Through those times of darkness, Mandela’s unfolding story became an inspiration that unfailingly energised us all.

His journey – from being the leader of an armed revolutionary group to an advocate of peace and forgiveness – became more important than the 27 years spent in prison. He later wrote: “As I walked out the door toward the gate that would lead to my freedom, I knew if I didn’t leave my bitterness and hatred behind, I’d still be in prison.”

By merely saying this, Mandela gave birth to fireflies of hope across the world. And by applying this insight in the public sphere, he added energy to a beacon that will light the way through all times.

Addressing the history of racial abuse in South Africa through the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was in itself a radical step – whatever disputes there may be about its actual achievements. By opting for this route the post-apartheid South African government, led by Mandela, rejected the old concept of Nuremberg-style trials of war criminals, which imprisoned those found guilty.

Instead, the TRC, led by Bishop Desmond Tutu, was founded on the principle that it is both possible and necessary to forgive – as long as those who committed the crimes publicly confess and express regret for their actions.

Devaki Jain, noted feminist scholar, accompanied her husband L.C. Jain when he was appointed India’s High Commissioner to South Africa – just as the work of the Commission was in full-swing.

Looking back on her time there and her meetings with Mandela, Jain says that in the absence of this approach South Africa could well have suffered a protracted civil war, as has happened in many other African countries. This has widely been recognised as perhaps the greatest achievement of the post-apartheid regime.

“During the hearings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, a very large section of South Africans were resentful of the process and the outcome,” Jain says. “Mandela’s support of Bishop Tutu’s endeavours was not appreciated, but Mandela’s stature as a genuine leader of the people was such that his desire and will were accepted.”

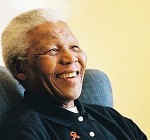

What enabled Mandela to do this? According to Jain, it was “…his extraordinary personality, which was commanding but at the same time convincing, a friend of the people, so he could lead them. If you recall Mandela’s face, the smile, the crinkled eyes, are very warm and enticing. You feel you have here a warm person, happy to be with people, able to reach out.”

Gopal Gandhi, who has served as India’s High Commissioner in South Africa, says that Mandela made the most of his training both as a lawyer and a boxer: “He knew when to advance, when to retreat, when to move to a side. He also knew the value of surprising his opponent. But above all, he knew that combat has codes, just as protocol does. His personal and political conduct was, if anything, supremely brave and supremely ethical, both values coming from his mind, not his heart.”

Mandela’s will to survive and finish the task may well be what he is remembered for centuries later. But to those who actually knew him, he will be honoured as an extraordinarily warm personality, says Jain: “…So easy to relate to, to feel close to, to love. His love of children gives us the clue, he just liked to be with them and in many ways was like them, happy to be happy.”

Will this legacy be clouded by doubts about the merits of Truth and Reconciliation? In retrospect, even Bishop Tutu has regretted that the TRC allowed many offenders to go free with impunity. Indeed, race relations in South Africa, as elsewhere, are far from being anywhere near the dream nurtured by M. K. Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., and Mandela.

Yet the refinement of the methods of striving is vital, precisely because the journey ahead is long and hard. As Mandela said in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech in 1993 – “we will have to go on striving to prove that King was right … when he said that humanity can no longer be tragically bound to the starless midnight of racism and war.”

It is by stressing the tenacity of this striving, rather than looking to measure outcomes, that we can best honour Mandela. As Gopal Gandhi has written, to stick a halo on Mandela “…would do no credit either to sagacity or cleverness. Let us see in him, rather, the retrieval of morality through intelligent action and a breakthrough for intelligence in ethical choices.”

Above all, it is these strengths that bolster people struggling for the realisation of ideals that are sometimes dismissed as being too lofty or remote. Moments of triumph, like Mandela walking out of prison, are important as good cheer and a fair wind in the sails of those who strive diligently for both justice and peace. It is the tenacity of vision and ethical choices that actually propels us to a future where there is indeed respect for all – regardless of class, colour, caste or creed.

Rajni Bakshi is the Gandhi Peace Fellow at Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2013 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited