This is part of an article series on India in the Global Commons. Click here to read the entire collection.

As the newest global commons, cyber space is anarchic in nature, with no formal comprehensive governance framework. The interconnectedness of cyber space, the low cost of launching a cyber attack, and the invisibility of cyber, makes it difficult to pinpoint the perpetrator with certainty. This is currently the great challenge to the global security establishment’s traditional notions of deterrence. Cyber attacks are on the rise, and now the dominant focus for international security, since the distinction between state and non-state actors has blurred.

Few attempts have been made by states in the last few years to create a global governance framework for cyber space. The most prominent is the UN Group of Governmental Experts (GGE) process, begun in 2004. But fundamental disagreements between the major powers – U.S., Russia and China – on how to manage cyber space have stymied the process of regulating cyber space, and the GGE collapsed in 2017 amidst disputes over applicability of specific international law principles for cyber space.[1]

In this global backdrop of flux, India is making a play to define a framework for the governance of cyber space. New Delhi’s Ministry of External Affairs and Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology are stepping up their cyber diplomacy through four endeavours: creation of cyber norms, managing internet governance, promoting the digital economy and emphasis on capacity-building.

1. Creation of cyber norms: India is entering this global commons through its historically active experience and involvement in international arms control and disarmament negotiations – an area where developing countries were often unheard and where India has often led. In cyber space, India has both advantages – a unique digital profile and a relatively high internet user base (estimated at over 400 million and expected to reach nearly 1 billion by 2021)[2] – as also the disadvantages of its peer nations –a lack of infrastructure and low internet speeds. Like other developing countries, India’s concerns in cyberspace reflect both the ‘pull’ of economic development (beneficiary of the free flow of data) and the ‘pressure’ of national security (concern with ever-increasing cyber attacks). This positions India as a legitimate representative for shaping the new cyber norms and their global governance.

So far, India has participated in the UN GGE process, where it advocated developing a common understanding on responsible state behaviour in cyber space and the adoption of confidence-building measures by states to address cyber threats, cyber terrorism and cyber crimes.[3]

India has supported other non-governmental efforts such as the Global Conference on Cyber Space (hosted in New Delhi in November 2017) and the Global Commission on the Stability of Cyberspace, both of which are developing cyber norms.[4] The newest effort comes from the UN Secretary General, António Guterres, who has set up a High-level Panel on Digital Cooperation, headed by China’s Jack Ma (Alibaba Group) and the U.S.’ Melinda Gates (Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation).[5] It will identify policy, research and information gaps, and propose ways to strengthen global digital cooperation. India is represented by Amandeep Singh Gill, a diplomat, who is an ex-officio member of this panel.

2. Managing Internet governance: This is an area where the global community has found some success, attributed in part to the controversial revelations of whistle-blower Edward Snowden, about the U.S. National Security Agency’s espionage and surveillance activities in 2014.

Here, India has been playing a positive role. Between 2014-16, the U.S. gave up its control of the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), which manages the global internet infrastructure. The U.S. wanted ICANN to be a multi-stakeholder body, incorporating national governments, business, civil society and academia, but Russia and China preferred a multilateral body, controlled by national governments. India announced its support for the multi-stakeholder model in 2015[6], and has encouraged Russian and Chinese support to the multi-stakeholder model, in particular through the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) forum. This has worked: successive BRICS declarations since 2015 have emphasised the need to involve relevant stakeholders in the evolution and functioning of the internet and its governance.[7]

3. Promoting the digital economy: The G20 focus on global economic governance has resulted in the creation of a Digital Economy Task Force to guide countries through the era of digital transformation.[8] India has been an important contributor to this process through its many domestic programmes: Digital India,[9] the Aadhar national ID project[10], the BharatNet project[11], financial inclusion through the Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yojana[12], a new domestic payments system RuPay[13], all resting on an indigenously-developed and exportable digital infrastructure called IndiaStack.[14]

These initiatives from a developing country are important at a time when the technology global majors are persuading governments to curtail ‘net neutrality’ – open and equal access to internet, which India has emphasised as non-negotiable. In July 2018, New Delhi announced the draft National Digital Communications Policy, which upholds net neutrality.[15] India’s non-discriminatory approach is in sharp contrast to the U.S. where net neutrality has faced setbacks in recent months,[16] and China, which despite a robust e-commerce market, still controls the internet through the state.

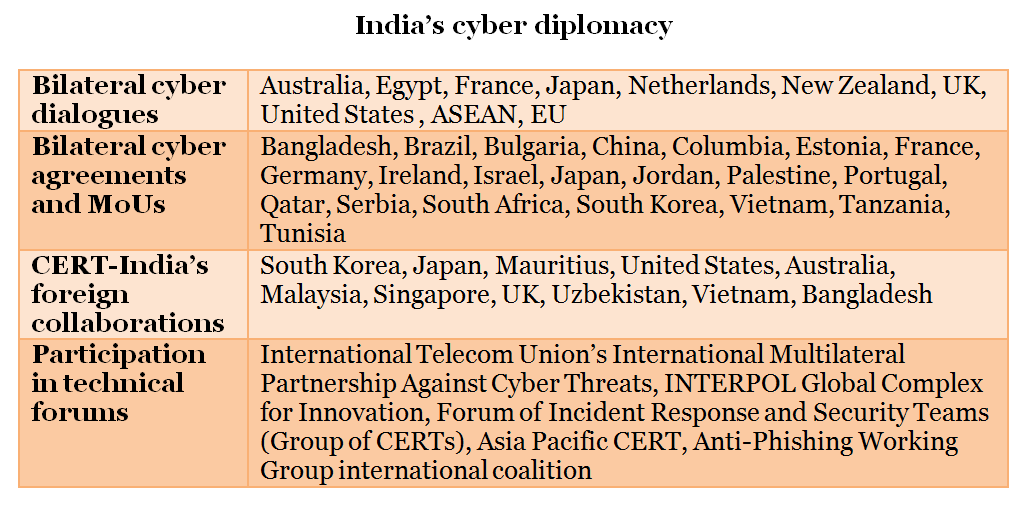

4. Emphasis on capacity-building: The key to tackle cyber threats and regulate cyber affairs is building capacity. In the last few years, as part of its cyber diplomacy, India has had bilateral cyber dialogues with eight countries and two organisations (European Union and Association of Southeast Asian Nations). These have included wide-ranging exchanges on Information Technology (IT) training programmes for India, threats posed by cyber crimes, cooperation between national Computer Emergency Response Teams (CERTs) and R&D in cyber security. India is also harnessing its IT expertise and share its cyber knowledge, through bilateral agreements and MoUs with other developing countries like Bangladesh, Tunisia, Vietnam (see table below). There is also interest from countries like Rwanda, Morocco and Sri Lanka on replicating India’s Aadhar-based national identity card project and the IndiaStack technology infrastructure. [17] [18]

These efforts are coalescing into an Indian vision for global cyber governance that will have greater resonance with developing countries that are just starting on the path of national digital transformation.

Sameer Patil is Director, Center for International Security and Fellow, National Security Studies, Gateway House.

This is part of an article series on India in the Global Commons. Click here to read the entire collection.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2018 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References

[1] Segal, Adam, “The Development of Cyber Norms at the United Nations Ends in Deadlock. Now What?,” Council on Foreign Relations, 29 June 2017, <https://www.cfr.org/blog/development-cyber-norms-united-nations-ends-deadlock-now-what>

[2] Press Information Bureau, Government of India, “Time to put rules to ensure that no one player dominates the industry, Smt. Smriti Zubin Irani Emphasises the need to attract, retain and develop talent which frees good content from the trappings of revenue needs,” 10 May 2018, <http://pib.nic.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1531781>

[3] United Nations General Assembly, “UNGA Resolution 70-237 entitled – Developments in the field of

Information and telecommunications in the context of international security: Comments of Government of India,” 2016 — A/71/172, 2016, <https://unoda-web.s3-accelerate.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/India.pdf>

[4] Press Information Bureau, Government of India, “India to Host Global Conference on Cyber Space 2017: A Giant Leap Towards a Secure and Inclusive Cyberspace,” 16 November 2017, <http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=173571>

[5] United Nations, “United Nations Secretary-General Appoints High-level Panel on Digital Cooperation,” 12 July 2018, <http://www.un.org/en/pdfs/HLP-on-Digital-Cooperation_Press-Release.pdf>

[6] ICANN, “Indian Government Declares Support for Multistakeholder Model of Internet Governance at ICANN53,” 22 June 2015, <https://www.icann.org/resources/press-material/release-2015-06-22-en>

[7] Department of International Relations and Cooperation, Republic of South Africa, “10th brics Summit Johannesburg Declaration,” 25-27 July 2018, <http://www.brics2018.org.za/sites/default/files/Documents/JOHANNESBURG%20DECLARATION%20-%2026%20JULY%202018%20as%20at%2007h11.pdf>

[8] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, People’s Republic of China, “G20 Leaders’ Communique Hangzhou Summit,” 4-5 September 2016, <http://www.g20chn.com/xwzxEnglish/sum_ann/201609/t20160906_3397.html>

[9] Ministry of Electronics & Information Technology, Government of India, “About Digital India”, <http://www.digitalindia.gov.in/content/about-programme>

[10] Unique Identification Authority of India, Government of India, “About Aadhaar,” <https://uidai.gov.in/your-aadhaar/about-aadhaar.html>

[11] Bharat Broadband Network Limited, “Status Of Bharatnet,” 12 August 2018, <http://www.bbnl.nic.in/index1.aspx?lsid=570&lev=2&lid=467&langid=1>

[12] Ministry of Finance, Government of India, “Scheme details,” <https://pmjdy.gov.in/scheme>

[13] National Payments Corporation of India, “RuPay,” <http://www.npci.org.in/RuPayBackground.aspx>

[14] IndiaStack, “What is IndiaStack?,” <http://indiastack.org/about/>

[15] Ministry of Communications, Government of India, “National Digital Communications Policy 2018,”1 May 2018, <http://dot.gov.in/sites/default/files/2018%2005%2025%20NDCP%202018%20Draft%20for%20Consultation_0.pdf>

[16] Federal Communications Commission, “Restoring Internet Freedom,” <https://www.fcc.gov/restoring-internet-freedom>

[17] Bhatia, Varinder, “India, Morocco finalise five pacts, but sign two,” The Indian Express, 1 June 2016, <https://indianexpress.com/article/india/india-news-india/india-morocco-join-hands-for-institutional-training-to-officers-promoting-cultural-exchange-2827700/>

[18] Srinivasan, Meera, “Sri Lanka is keen to introduce an Aadhaar-like initiative,” 21 December 2017, <https://www.thehindu.com/news/international/sri-lanka-is-keen-to-introduce-an-aadhaar-like-initiative/article22099494.ece>[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]