The India-Armenia relationship has always been historically warm. This closeness continued even after Armenia became one of the republics[1] of the erstwhile Soviet Union and India’s independence in 1947. With Armenia’s independence on 21 September 1991 and with both countries setting up embassies in each other’s capital cities, the bilateral is now being celebrated, through various prisms. One is that of culture, evident in the 2021 release of a documentary Frunzik Mkrtchyan: India remembers me on the legendary Soviet actor of Armenian descent who starred in Hindi films like Alibaba Aur Chalees Chor and Sohni Mahiwal in the 1980s[2].

Image 1: Poster of documentary ‘Frunzik Mkrtchyan: India remembers me’

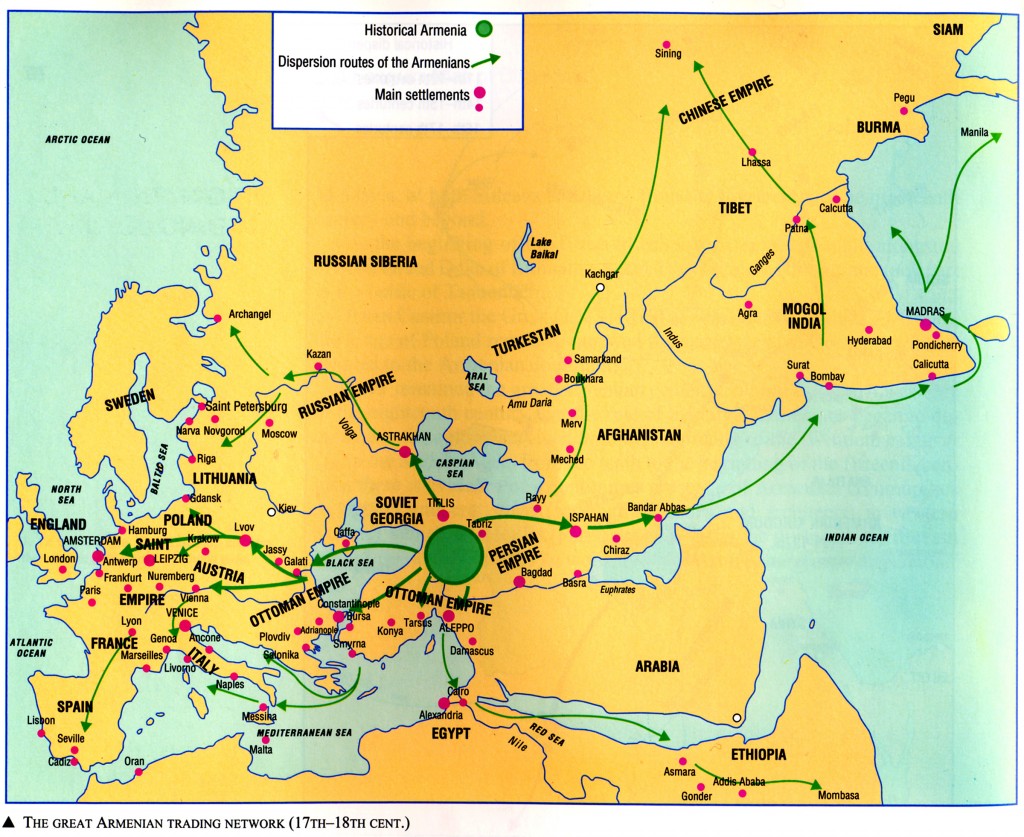

But this 20th-century history gives no indication of how old and nuanced India-Armenia relations really are. Like most countries where old Armenian diasporas are settled, India-Armenia contacts began with trade. The high mountainous terrain of their country had little in land resources and Armenians took to trading in the overland Eurasian trade routes. They had the advantage of being strategically located on the Caucasian Isthmus between the Caspian and the Black Sea[3] thereby acting as a bridge between east, central and south Asia with west Asia and Europe. Uniquely too, as in the past[4] and today, it is an orthodox Christian nation with predominantly Muslim neighbours. The earliest known Armenians who traveled to the Indian subcontinent for trade was in the 11th C.E.,[5] sojourners who returned home after the completion of their business. Armenian Christian traders who traveled to distant countries were commenda partners[6], whose capital was provided by one of the handful of big Armenian merchant families from Old Julfa in Armenia. Later in the 17th -18th centuries, these merchant families were relocated to New Julfa, Persia. (See Part 1)

Image 2: The Great Armenian trading network of the 17th and 18th centuries

Source: The Penguin Atlas of Diasporas. By Gerard Chaliand and Jean-Pierre Rageau. https://commons.princeton.edu/mg/the-great-armenian-trading-network-17th-18th-century/

The subcontinent was the bridge connecting traders by sea to Southeast Asia as far as Manila and across the Pacific Ocean to Acapulco. Land routes from north India took them to the Tibetan capital of Lhasa and imperial China’s Sinking.[7] It was the maritime Indian Ocean network that was by the 17th century by far the largest and most important route and was balanced in the west by the Eurasian and Mediterranean circuits. [8]

In community chronicles[9], merchants with their families first began settling in the Mughal Empire due to the encouragement of Emperor Akbar (r.1556-1605) who encouraged foreign traders to settle in his territories. Akbar is always referred to as the ‘Great Emperor’ or mentor of the Armenian people in the subcontinent, particularly favored because they were astute businessmen who endeared themselves to the local population with their frugal ways and multi-lingual skills, and a very low-key, community-centric orthodox Christian presence. Armenian merchant communities settled not just in Akbar’s capital city Agra where the earliest Armenian church was built, but Lahore, the port of Surat, Saidabad (near Murshidabad, Uttar Pradesh), and by the early half of the 17th C in Mughal territories in Bengal including the villages of Kalikata, Govindapur, and Sutanati which would grow into the English East India Company’s capital city of Calcutta. They also settled on India’s southwest coast in Malabar, in the south in Pulicat (close to the Golconda mines), and on the southeast coast in Mylapore (St. Thomė).[10]

Armenian traders were famous for the Iranian silks they sourced from manufacturing centers in northwest Persia, and the pearls they sourced from Basra and other Gulf pearling centers. The demand in Europe for Iranian silks and cotton cloth, the latter mostly manufactured in various weaving centers on the subcontinent but passed off as Iranian, expanded Armenian trade to Europe. Also sourced from India into European centers like Amsterdam by the Armenians were diamonds, precious and semi-precious stones. The famous Orloff diamond in the scepter of Russian Empress Catherine the Great, was mined in Golconda and ultimately sold by an Armenian merchant to Catherine’s lover Count Orloff who gifted it to the Empress in the hope of wooing her back.

Image 3: All Savior’s Monastery in New Julfa, Isfahan

The importance of India to Armenian history other than trade, began after the destruction of the Armenian financial headquarter of New Julfa in Persia by 1747. New Julfa is a suburb of Isfahan where wealthy Old Julfan merchant families were resettled by Shah Abbas I in 1605. (See Part 1) This Christian suburb of merchant families contributed to 80% of the Safavid state budget by 1628 and were bankers to the Shah, but they supported a widespread Armenian diaspora commercially, financially, culturally, and religiously.[11] It was when the big merchants were forced to relocate yet again in the mid-18th century that many dispersed to trading towns in Russia and Europe. But a majority settled in India.

This latter wave of immigrants to India were at the forefront of reinforcing a national identity for the Armenian people who lived dispersed across the world and without an independent country. The English colonial city of Madras which was an important Armenian trading hub soon became home to an Armenian liberation movement whose most prominent member was the affluent scholar merchant Shahamir Shahamirian (1723-1797). Shahamirian was an ardent patriot who drafted a proto-Armenian constitution and was instrumental in setting up the world’s first Armenian press. It was at the second Armenian press also in Madras that Azdarar (Intelligencer), the first-ever Armenian journal was published between 1794 and 1796.[12]

The nationalism played out in different ways. Two Chinese porcelain teacups and saucers in the Kalfayan collection of the Museum of Byzantine Culture in Thessaloniki (Greece) are believed to be part of a set commissioned by the patriot Shahamirian. Both sets have inscribed in Armenian ‘For the Kings of Armenia. Date 1244’ which corresponds to 1794, the aim being that the inscription is a constant reminder of the once glorious history of the Armenians. Earlier in 1688, Surat merchant Khoja Phanoos Kalandar had signed a Treaty with the English East India Company in London on behalf of the ‘Armenian nation’.[13] Although Kalandar was a shrewd negotiator who acquired for his community privileges that included the right to reside and travel freely in Company towns and garrisons and were granted all privileges ‘it allowed its own and other English merchants’ provided they preferred to transport their goods aboard Company ships. It was the ‘shipping’ condition that community historians bemoaned weakened the traditional trade of the Armenians by shipping Armenian goods directly to Europe by bypassing West Asia, North Africa, and the Mediterranean.

By the 19th century, Calcutta was the most populous settlement of the Armenians, and home to wealthy and influential merchants like Arratoon Apcar, Astvatsator Murudghanian, and David A. Davidian. The Armenian College & Philanthropic Academy (APCA) was established in 1821 by Murudghanian and fellow Armenian merchants with the purpose to “train and educate their (Armenian) children in the language and faith of their forefathers” so they can preserve their national identity in their adopted country. [14] Although all sizeable Armenian communities have a school or at the least classes conducted by the local pastor, ACPA’s role has been singular in attracting and teaching international Armenian students over the years, particularly those from Iraq, Iran, and Armenia.

It is here that India’s greatest soft power truly lies – not just in Armenia but amongst the transnational Armenian communities who number 8-10 million as against Armenia’s population of about 3 million. It is in the childhood memories of the thousands of Armenian students who have studied in India, the Armenian boys from ACPA who played rugby as part of Calcutta’s Armenian rugby team, and in the shaping of a distinct cultural and national identity that grew from an 18th century intellectual movement with roots in Madras.

Sifra Lentin is Fellow, Bombay History, Gateway House

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here

For permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in

©Copyright 2022 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorised copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References

[1] Armenia became part of the Soviet Union in 1929. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, it became the independent Republic of Armenia on 21 September 1991. Armenia like all former Soviet republics is part of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS).

[2] Alibaba Aur Chalees Chor was released in 1980, and the Indo-Russian venture Sohni Mahiwal in 1984.

[3] The Republic of Armenia is former Soviet Armenia.

[4] Armenia adopted orthodox Christianity as a state religion as early as 301 C.E. After the fall of the Byzantine Empire in 1453, Armenia has been surrounded by Muslim nations with the exception of Russia to its north.

[5] It is believed that Thomas of Cana who arrived on the Malabar Coast, today part of India’s southern state of Kerala, in the 4 C.E. was an Armenian.

[6] The Commenda partnership was unique to the Armenian trade, where the agent (junior partner) was typically a male family member who traveled and traded abroad on behalf of the head of the family (Khoja). On returning after a few years (about 2-5 years) and when accounts were squared, the Commenda agent took a share of about 20% of the profits. This helped the circulation of merchants, goods and credits through the trade networks.

[7] Armenian merchants were resident in all these centers by the 17th-18th centuries.

[8]Aslanian, Sebouh David, From the Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean: The Global Trade Networks of Armenian Merchants from New Julfa (Los Angeles, University of California Press Berkeley, 2011). p. 2

[9] Lang, David Marshall, The Armenian: A People In Exile (London, Unwin Paperback, 1989), p. 89. Also, Seth, Meshvrob Jacob, Armenians in India from the Earliest Times to the Present Day : A Work of Original Research (New Delhi, Asian Education Series, 2005), p. 102.

[10] The Armenians wielded tremendous influence in the Mughal Court. Akbar’s chief legal advisor Abdul Hai was an Armenian, and one of his wives Maryam is believed to be Armenian.

[11] Ohta, Alison, J.M. Rogers and Rosalind Wade Haddon, eds., Art, Trade and Culture in the Islamic World and Beyond From the Fatimids to the Mughals Studies (Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2017), p. 178.

[12] Lang, David Marshall, The Armenians: A People Exiled, (London, Unwin Paperback, 1989) p.94.

[13] The 22 June 1688 Treaty, in addition to religious freedom, and no-to-low taxes, allowed the Armenians to reside and travel freely in Company towns and garrisons and granted all privileges ‘it allowed its own and other English merchants’ provided they preferred to transport their goods aboard Company ships. This Treaty, according to community historians undermined the community’s traditional trade. The Company’s motive was to deflect Armenian trade goods away from the Gulf ports, Ottoman territories, Egypt, and the southern Mediterranean littoral, directly to England.