On 18 February 2022, Prime Minister Modi’s BJP government signed its first free trade agreement since coming to power. It did so with the UAE, India’s third largest trade partner[1] and key supplier of crude oil.[2]

Historically, close ties have been a characteristic of the India-UAE bilateral, a reason why both nations made haste – a record 88 days of negotiations – in finalising this deal in the 50th year of the founding of the UAE. It will come into force on May 1.[3], [4]

As early as the second half of the third millennium B.C.E. a coasting trade existed between the ancient Harappan civilisation in the Indus Valley and the Mesopotamian (Sumerian) in the valley between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. The latter’s trading sphere was inclusive of littoral regions in the Persian Gulf, like today’s UAE. The Thattai Bhatias of Sindh are believed to be the first known Indian traders active in that region. Trade accelerated with the establishment of Baghdad in 762 C.E. as the capital of the Abbasid dynasty.[5], [6]

By the late 18th and early 19th centuries, colonial Bombay housed the Persian Gulf’s many trading communities: Arabs, Jews, Armenians, and Persians, due to its large, open sea, sheltered harbour, and many goods for export like raw cotton, cloth, indigo, spices, wood, rice and ghee. It bought Gulf imports of horses, dates, coffee and pearls. The Emirati kingdoms were once renowned for their pearls. By the 19th century, Bombay had the largest pearl market – Moti Bazaar – east of the Suez.

The Bombay Presidency-UAE relationship went beyond trade.

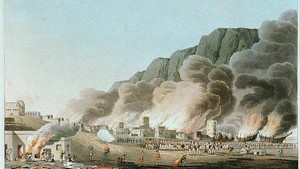

Bombay city[7] administered the defense, foreign policy, fiscal and monetary policy of nine Persian Gulf coastal kingdoms thanks to treaties[8] between the English and these kingdoms. It began innocuously with a maritime treaty in 1820, signed to end the coastal tribes’ harassment of British and Indian ships in the region.[9], [10], [11]

The Royal Navy and Bombay Marine joint fleet launched naval operations to transform what it termed the ‘pirates coast’ into a ‘’treaty coast’[12] but it took many years and treaties to establish actual control.

The last treaty, signed in 1892 and aimed at thwarting Russian and French influence, entrusted Great Britain with management of the external relations of the nine treaty states. This was a step up from the 1853 Perpetual Maritime Truce under whose terms Britain provided protection for those sheikhdoms from external aggression, in return for trading privileges.[13]

Under these treaties, the Indian rupee became legal tender in the nine treaty kingdoms.[14] The Bombay Rupee and later the Indian Rupee were already popular and widely used in the Persian Gulf states because of the robust existing trade. When the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) was established and headquartered in Bombay in 1935, it handled the treaty states’ sterling reserves.

At India’s independence in 1947, Great Britain took over the states’ administration, with the exception of the management of the rupee which remained under the RBI’s purview.

This inadvertently strained India’s slim foreign exchange reserves. Rupees were smuggled out of India to buy cheaper gold in the Gulf that was smuggled back into India and sold at a profit. When Indian rupees were exchanged into sterling pounds at Gulf banks, they far exceeded the Emirati kingdoms’ sterling reserves at the RBI.[15] To solve the problem, the RBI issued Gulf Rupees in 1959, brightly-coloured notes with serial numbers beginning with a ‘Z’ – not legal tender in India, and exchangeable only at the RBI’s Bombay office.

Signing of the UK-UAE Friendship Treaty

The devaluation of the Indian rupee in the aftermath of the India-Pakistan war (1965) and the famine of 1966 spurred the Emiratis to shift to their own currencies. In December 1971, seven of the nine treaty states formed an independent, sovereign, federal structure, the United Arab Emirates, with their own currency, now the Dirham.

India and the UAE have come full circle. The new trade deal will likely expand to other Gulf nations like Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, and Oman, countries where the Indian rupee once reigned as legal tender.

Sifra Lentin is Fellow, Bombay History, Gateway House.

This article is the second in a two-part series. Read the first part here.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2022 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References:

[1]The India-UAE trade for 2021-22 stood at $65.17 billion (Indian exports were $24.96 billion and Indian imports were $ 40.21 billion).The expectation is that trade will reach $ 100 billion with the CEPA coming into force.See https://tradestat.commerce.gov.in/eidb/iecnt.asp

[2] Crude oil sales from the UAE to India were $ 10.9 billion in 2021. See: https://tradestat.commerce.gov.in/eidb/Icntcom.asp .

[3] The UAE is made up of seven Emirati kingdoms, namely, Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Sharjah, Ajman, Umm Al-Quwain, Fujairah and Ras Al Khaimah. As the former Trucial (Treaty) States there were two additional sheikhdoms: Bahrain and Qatar.

[4] See https://www.livemint.com/news/world/the-uae-welcomes-a-wider-india-gcc-trade-agreement-11648230149828.html

[5] The Abbasids were the second of the Islamic caliphates to be established. By this time too, Basra, which is downriver from Baghdad, located in the delta of the Tigris-Euphrates rivers and strategically at the head of the Persian Gulf, was already known to host Indian traders from Kutch, Saurashtra and Gujarat (Jains, Hindus, Muslims), whilst Arab, Jews, Armenians and Persian traders during this period had settled for trade on the Subcontinent’s west coast and as far south as the pepper coast of Malabar.

[6] This ancient Indian Ocean trade’s raison dé etre was open seas, barter, interchangeable multilateral currencies, and a multicultural trading system – though piracies and conflicts between local powers were frequent – was upended slowly with European intervention beginning with the discovery of the direct sea route by the Portuguese in 1498 and their attempt to control the Indian Ocean maritime trade routes by use of force. (See https://www.gatewayhouse.in/portuguese-string-of-ports/)

[7] Bombay as the capital city of the Presidency of Bombay administered the external relations of the then nine Trucial (Treaty) States. Bombay’s proximity to the Gulf region, the numerous Gulf traders residing in the city in the 19th century, and the fact that it was a major port for this trade, went in its favour.

[8]The first was the General Maritime treaty (1820), then the Anti-Slavery treaty (1847), the Perpetual Maritime Truce (1853), then additional Anti-Slavery treaties of 1856, additional articles added to the Perpetual Truce of 1853 for the protection of telegraph lines and stations (1864), Treaty of 1879 on the treatment of absconding debtors, and finally the Exclusive Agreement of 1892 which brought the external relations, defense and fiscal and monetary administration under the purview of Great Britain. It has to be noted that not all sheikhdoms signed these treaties at the same time, the original nine kingdoms signed in different years.

[9] There was an earlier treaty of 1805 which the English Company did not succeed in enforcing.

[10] https://www.gatewayhouse.in/kanhoji-angre-indias-first-naval-commander/

[11] https://www.gatewayhouse.in/historical-perspectives-on-piracy-the-british-empire-in-the-persian-gulf/

[12] This was the colonial narrative of the time. Contemporary historians like Sugato Bose in his book A Hundred Horizons: The Indian Ocean in the Age of Global Empires, dispute this because of the double standards of the Europeans. The Europeans imposed “Mare Clausum” or closed seas in the territorial waters of their colonies but refused in turn to pay to traverse through the waters of local coastal powers.

[13] This was much like what was being done with the many native Indian kingdoms on the Subcontinent.

[14] Bhandare, Shailendra, Money On The Move: The Rupee and the Indian Ocean, in Prabha Ray, Himanshu, and Edward A. Alpers, Eds., Cross currents and community networks: The history of the Indian Ocean world (New Delhi, OUP, 2007) p. 226.

[15] Rupees could be exchanged at any bank in the Gulf for sterling pounds but when special Gulf Rupees were issued, they could be exchanged only at the Bombay office of the RBI. The Rupee 1 notes were issued by the Indian government.