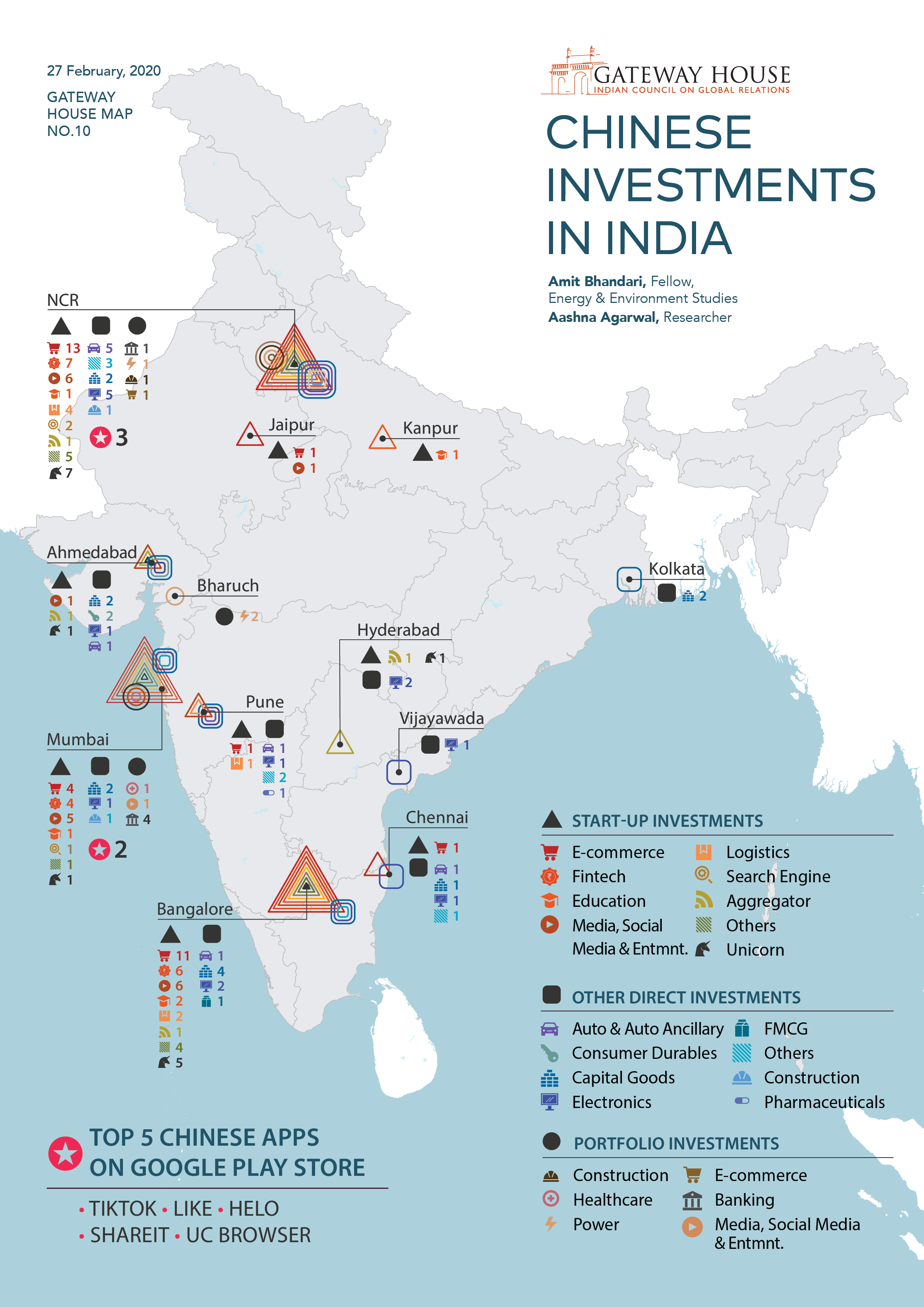

Over the last five years, China has quietly created a significant place for itself in India – in the technology domain. Unable to persuade India to sign on to its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China has entered the Indian market through venture investments in start-ups and penetrated the online ecosystem with its popular smartphones and their applications (apps).

Chinese tech investors have put an estimated $4 billion into Indian start-ups. Such is their success that over the five years ending March 2020, 18 of India’s 30 unicorns are now Chinese-funded. TikTok, the video app, has 200 million subscribers and has overtaken YouTube in India. Alibaba, Tencent and ByteDance rival the U.S. penetration of Facebook, Amazon and Google in India. Chinese smartphones like Oppo and Xiaomi lead the Indian market with an estimated 72% share, leaving Samsung and Apple behind.

There are three reasons for China’s tech depth in India. First, there are no major Indian venture investors for Indian start-ups. China has taken early advantage of this gap. Alibaba’s 2015 investment in 40% of PayTM, a digital payments platform, paid off barely a year later when in November 2016, the government of India demonetised its large currency notes and simultaneously promoted a move to a cashless economy. PayTM benefitted from Alibaba’s superior fintech experience, which it applied to India seamlessly, making it a dominant player.

Second, China provides the patient capital needed to support the Indian start-ups, which like any other, are loss-making. The trade-off for market share is worthwhile. Third, for China, the huge Indian market has both retail and strategic value. Therefore, companies like Alibaba and Tencent have different considerations and horizons for their investments. In contrast, Western venture money is mostly through funds like Sequoia and SoftBank.

China has seen another early opportunity in India – the potential shift to electric mobility, where China has expertise. India is the world’s fifth-largest auto market; the sector is the country’s most robust and globalised export and it is a bellwether for the economy. China’s BYD has been pushing its electric buses in India, with limited success. In traditional autos, which is 99% of the market, China is using the recognisable, but distressed, global auto brands like Volvo and MG, which it acquired to enter the Indian market. So far, Chinese automakers have invested $575 million in India. The competition in India is fierce, and it’s with Indian and Asian automakers like Suzuki, Hyundai and Toyota, even as U.S. automakers withdraw.

The Belt and Road Initiative carries with it Chinese products and standards, both virtual and physical. India may have sidestepped the physical corridor, but has unwittingly signed up for the virtual corridor.

Amit Bhandari is Fellow, Energy and Environment Studies, Gateway House.

Aashna Agarwal is Researcher, Gateway House.

Visualized and mapped by Debarpan Das.

You can read more Gateway House content here.

For interview requests with the authors please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2020 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

Disclaimer: While every effort has been made to ensure that data is accurate and reliable, these maps are conceptual and in no way claims to reflect geopolitical boundaries that may be disputed. Gateway House is not liable for any loss or damage whatsoever arising out of, or in connection with the use of, or reliance on any of the information from these maps.