This is part one of a two-part series. Read part two here.

Fifty-five years ago, India had a vibrant ethnic Chinese population, living mostly in Calcutta and Bombay. Calcutta had two China Towns: Old China Town (Cheenapara), centred on Colootola Street and Dr. Sun Yat Sen Road [1], and New China Town (Dhapa or Tangra) on the outskirts of Calcutta, during the Second World War. It was famous for the tanneries, run exclusively by local Chinese. Bombay also had two China towns, if smaller than Calcutta’s, located on Nawab Tank Road (Mazagaon) and Shuklaji Street (Nagpada).

Today these are only remnants of history, marked by temples to Kwan Tai, Confucius, and even a Chinese temple to the Hindu Goddess Kali (in Tangra). [2] The community once possessed everything they needed – from mahjong clubs, grocery stores (which Calcutta still has) and schools, to printing presses and hawkers selling dim sums, noodles and soup.

Indians have usually viewed the local Chinese in terms of stereotypes, preferring Chinese restaurants – as opposed to those run by Indians – for authentic fare. They have also associated them with hip hair-dressing salons, and dental clinics, operated by Hupei Chinese doctors, once famous for the traditional remedies they used for treating cavities. Those who remain in practice today have all qualified from Indian dental colleges!

The 1962 war changed the course of history for the Chinese presence in India. In the 10 years following the war, 3,000 Indian Chinese remained interned till 1965-66 in Deoli Camp (in the Rajasthan desert) and prisons – if they had not opted for deportation to Communist China[3] [4]. Those who were not interned faced harassment as their businesses were boycotted and families treated with suspicion. The community felt their movements and employment opportunities to be greatly circumscribed. Chinese fitters and carpenters working in the Mazagaon Dockyards, for instance, were all laid off. Government jobs were now out of bounds. And residents of hill stations like Darjeeling, Shillong and Markum (now sensitive border areas) were impelled to move to Calcutta. This impelled the migration of Chinese families West to Canada and the United States, and East to Hongkong and Australia.

Half a century later, the Toronto community, in particular, because of its larger numbers, still retains a cultural affinity with India – be it speaking the language, watching Bollywood movies. The Greater Toronto suburbs of Markham and Scarborough have the largest Bambaiya Hindi- and Bengali-speaking Indian Chinese community. They also founded their own clubs and associations, such as Hakka Helping Hands for its senior citizens, and the Association of Chinese India Deoli Internees, the latter being a living reminder of the darkest years, in an otherwise unblemished, centuries-old history of the Chinese community in India.

Early history: Chinese ‘sojourners’ to the sub-continent

The history of India’s Chinese community is part of a larger global narrative about the Overseas Chinese, who began emigrating – at first, the men alone – during the politically fraught period of the Late Qing dynasty (1644-1911), a period marked by internal unrest and European territorial concessions [5] at its treaty ports.

The first recorded presence of a Chinese person in Calcutta is Acchi (Yang Da Zhao) in 1778, believed to be a sailor on a Chinese merchant ship that was caught in a storm in the Bay of Bengal, and whose ship and crew took shelter in Calcutta harbour.

There are varying versions to the story, but, in sum, then Governor General of British India, Warren Hastings, gave Acchi a grant of land (400 acres in what is today Kolkata’s Achipur) to develop a sugar plantation, sugar mill, and piggery, whereby pork and lard could be supplied to the English residents. He was also permitted to bring a batch of 110 Chinese workers from China, who quickly abandoned him when enticed by other resident Chinese – this suggests an earlier presence of the community – to take up more lucrative vocations. Hastings now allowed Acchi to import indentured labour from China. This marks the beginning of Calcutta’s Chinese settlement. [6]

Though Acchi died soon after he brought in a fresh batch of labourers, the migration of Chinese labour into Calcutta was well underway. It was slow, but continuous: neither an outcome of large-scale importation of indentured labour (as in Malaysia), as most early migrants were sailors, nor a major influx during a given period. According to the India Census of 1951 and 1961, the population of ethnic Chinese peaked at 9,215 and 14,607 respectively, [7] though community members speak of Calcutta alone having a population of about 30,000 Chinese. [8]

The creation of the Indian Chinese diaspora was very much an outcome of the colonial migrations of the late 18th, 19th and first half of the 20th centuries, which also resulted in the creation of Indian diasporas in the network of colonial ports across the world – a reason why Prime Minister Narendra Modi has a large and active expatriate community to address on his travels abroad, a constituency he hopes to activate and connect back to India, their homeland.

There is one difference between the Indian and Chinese diasporas, according to Ming-Tung Hsieh, a Calcutta-born Chinese, who schooled in Kalimpong, and settled in Mumbai in 1966 after his release from Deoli Camp: “They never ventured to Africa or the Gulf. Calcutta was the last port, where you made money and returned. My father said that there was a regular steamer service, so it was possible to return home.” [9]

These early residents were termed “sojourners” as they often went back home to marry–the steamer service ran between Calcutta and Canton (Guangzhou) and/or Hongkong – and also remitted their earnings to their families in China. This practice was common even during the Qing Dynasty and during the Republic of China (1911-1949).[10]

Baba Ling, owner of the famous Mumbai restaurant, Ling’s Pavilion, remembers his family’s migration well: “My father, Yick Sen Ling, came to Bombay in 1938 from a village named Santau in the southern province of Canton. He, my cousin Chen, and Uncle Ling, opened the first Chinese Museum in the old Cottage Emporium just outside the BEST bus depot on Colaba Causeway.” With the establishment of a Communist government in Beijing on 1 October 1949, the free flow of people, capital, and goods into and out of mainland China stopped. Overseas Chinese not only lost contact with family and friends in China, but had their landholdings and properties in China confiscated by the Communist government. The Ling family closed down the museum and opened Nanking Restaurant in Colaba in 1945, [11] making them today the oldest and third generation Indian Chinese family in the restaurant business.

The Second World War years

The war years (1939-45) and those following it were marked by a period of empathy and close contact between nationalists in India and China. The Second Sino-Japanese War (beginning 1937) led to a peaking of nationalist sentiment in China, bringing together the warring Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and then Nationalist government, headed by the Kuomintang (KMT) party. Coterminously, the Indian nationalist movement was gaining momentum. The similarity in political goals–to evict foreign imperialists from their country – resulted in exchanges at various levels. The Indian National Congress funded a five-member Indian Medical Mission (IMM), headed by Dr. Dwarkanath Kotnis, to provide emergency help for Chinese soldiers fighting on the Japanese front. [12]

The leaders from the two countries were in touch too, such as the time when Congress leader (and later, independent India’s first prime minister) Jawaharlal Nehru visited Chongqing, the war capital of the Chinese (Kuomintang) government, in 1939.[13]

During their February 1942 visit to India, then president of the Republic of China, Chiang Kai-shek, and Madam Chiang, insisted – despite the British Indian government’s consternation – on calling on Indian leaders, such as Gandhi and Nehru. The purpose of their visit was to oversee the Chinese expeditionary forces being trained in Indian military cantonment towns near Calcutta and Bombay. These troops (60,000) were being deployed on the Burmese and Assam Front to secure the supply lines into southern China. The Japanese army had already overrun Burma by then and was on India’s borders. [14]

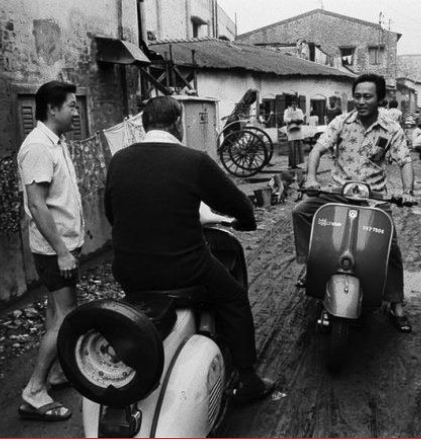

China Towns in both Calcutta and Bombay were having their heyday then, with Chinese soldiers, based in nearby cantonment towns, frequenting them for food and recreation. Community members say many stayed back, swelling the local Chinese population in Calcutta to a peak of 30,000.

By the time India gained Independence on 15 August 1947, the oldest Chinese families already had a presence in India that went back at least three or four generations.

Two years later, with the Communist takeover of mainland China, there was an abrupt breakdown in communication between Indian Chinese and their networks in China. They now invested their earnings in business and property in India itself.

In the months before the War, they were asked to report to local police stations for registration and classification based on their legal status. Most considered themselves naturalised Indians, having been born in India, with their families resident here for generations. They were unaware that it was only those born after the Indian Constitution came into being on 26 January 1950 who could be considered naturalised citizens. Those who held People’s Republic of China (PRC) passports were repatriated while some of those who had Indian passports were deported for being pro-Communist. Yet others had expired KMT party papers or only ‘resident permits’. Those interned by the Indian government were considered pro-Communist. Others were either residents of sensitive border districts or victims of business rivalry, and deemed to be spies. [15]

This turn of events is particularly ironic since India was among the first countries to recognise and support the PRC, and the first non-communist nation to establish a diplomatic mission in Beijing.[16] At that time, New Delhi did not envisage ever going to war with China, but border tensions, 1950 on, and the Dalai Lama’s dramatic escape from Tibet into India in 1959, heightened the Sinophobia in the countdown to the ’62 war.

It had a terrible psychological impact on the Chinese in India. Those released from jails or the Deoli Camp found their properties sold or illegally occupied, which resulted in Chinese migration out of India. The China Towns of yore no longer exist in Calcutta or Bombay. The original residents have given way to a variety of other Indian communities. Indian Chinese, settled abroad, return to Kolkata and Mumbai annually to visit those who stayed behind and bow before their ancestors’ tombs. In Toronto, they speak Bengali and Hindi, sing old Hindi songs at weddings, and never pass up a chance to eat tandoori chicken. They still don’t quite fit in with other Overseas Chinese communities as they retain a distinct Indian identity, with a few among them acquiring an NRI and PIO status that offers them the best of both worlds. As for those who stayed back, they run some of the best Chinese restaurants while the women are still sought after as hairstylists. As one interviewee put it, “Acche din aaye hain… we are happy here!”

Sifra Lentin is Bombay History Fellow at Gateway House.

This is part one of a two-part series. Read part two here.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in or 022 22023371.

© Copyright 2017 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References

[1] The first China Town (in Bengali: Cheenapara) in central Kolkata, appears to have been settled by Chinese emigrants before 1778. It was an aggregation of localities consisting of Chattawala Gully (lane), Chuna Gully, Colootola Street, Dr. Sun Yat Sen Road. Its boundaries in the 1960s was: Phears Road (east), Chitpur Road (west) that housed Tiretti Bazaar, Colootola Street (north) and Bow Bazaar Street (south). While Bentinck Street, a commercial corridor just south of Chitpur Road, was famous for its Chinese shoe-makers and their retail outlets.

[2] The author would like to thank Rafeeq Ellias (photographer and documentary film-maker) for his insights into the Indian Chinese and those who settled abroad. His documentaries on the community include the award winning BBC film, The Legend of Fat Mama: Calcutta’s melting ‘wok’ <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pQ2QJSHWOqQ>, and Beyond Barbed Wires: A Distant Dream <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uF9QFItw56k>

[3] Many of those deported were pro-communist sympathisers and those who wanted to escape the confines of Deoli Camp and the jails. Most were long- time residents and were born in India. In the spring of 1963, the People’s Republic of China sent ships to Madras from where 2,345 Indian Chinese were repatriated to China. Deportations also took place across the land border.

[4] Chatterjee, Ramakrishna, ‘The Chinese Community in Calcutta: Their Early Settlement and Migration” in Madhavi Thampi, ed,, India and China in the Colonial World (New Delhi: Social Science Press, Paperback, 2010), pp. 62-63; also, Li, Kwai-Yun, Deoli Camp: An Oral History of Chinese Indians from 1962 to 1966 (Self-published M.A. Thesis Ontario Institute for Studies in Education)

[5] Within the treaty ports, Western subjects had the right of extra-territoriality—i.e., they were under the control of their own consuls and were not subject to the laws of the country in which they resided. Eventually an independent legal, judicial, police, and taxation system developed in each of the ports, although the cities themselves were still nominally considered a part of the country in which they were located.

[6] Hsieh, Ming-Tung, India’s Chinese A Lost Tribe (Self-published by author, Kolkata, Reprint 2012), pp.143-44. Also, Chatterjee, Ramakrishna, ‘The Chinese Community in Calcutta: Their Early Settlement and Migration” in Madhavi Thampi, Ed., India and China in the Colonial World, (New Delhi: Social Science Press, Paperback, 2010), p. 56-57.

[7] Ibid, Thampi, Ed., pp. 61-62.

[8] Hsieh, Ming-Tung, India’s Chinese A Lost Tribe, (Kolkata, Self-published by author, Reprint, 2012), p. 259.

[9] Interview with Ming-Tung Hsieh on 17 October 2017.

[10] ‘Early Republican Period’ and ‘Late Republican Period’ in Introduction & Quick Facts: China. <https://www.britannica.com/place/China/Cultural-institutions#toc214398> (Accessed on 29 October 2017)

[11] Interview with Baba Ling on 19 October 2017.

[12] Dr. Dwarkanath Shantaram Kotnis went to China as part of a five-member Indian Medical Mission (IMM) funded and put together by the Indian National Congress in 1938. He was the only member of the team who died while on duty in China. He served on the Chinese war front during the Second Sino Japan War. Today, Dr. Kotnis’ work on the battlefront in saving the lives of hundreds of Chinese soldiers has come to symbolize India-China Friendship. The IMM itself was the first mission sent by an Asian country.

[13] Nehru was keen to proceed to Yan’an (the Chinese communist headquarters) to meet Mao Zedong and members of the IMM, who were working closely with the Eighth Route Army* since 1938. But the Second World War intervened on 1 September 1939. He did meet a leader of the Chinese Communist Party, General Ye Jianying, who briefed him on the situation in China.

The Eighth Route Army was created from the Chinese Red Army on September 22, 1937, when the Chinese Communists and Chinese Nationalist Party formed the Second United Front against Japan at the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War, as the Second World War is known in China. Together with the New Fourth Army, the Eighth Route Army formed the main Communist fighting force during the war and was commanded by Communist party leader Mao Zedong and General Zhu De.

Saklani, Avinash Mohan, “Nehru, Chiang Kai-shek, and the Second World War” in Madhavi Thampi, Ed., India and China in the Colonial World, (New Delhi: Social Science Press, Paperback, 2010), p. 169.

[14] Saklani, Avinash Mohan, “Nehru, Chiang Kai-shek, and the Second World War” in Madhavi Thampi, Ed., India and China in the Colonial World, (New Delhi: Social Science Press, Paperback, 2010), pp. 177-78. Also <https://www.britannica.com/place/China/War-between-Nationalists-and-communists>

[15] Hsieh, Ming-Tung, India’s Chinese A Lost Tribe (Self-published by author, Kolkata, Reprint 2012), pp.197-98. Also, Chatterjee, Ramakrishna, ‘The Chinese Community in Calcutta: Their Early Settlement and Migration” in Madhavi Thampi, Ed., India and China in the Colonial World (Social Science Press, New Delhi, Paperback 2010), pp. 62-63.

[16] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, India-China Bilateral Relations, (New Delhi: Ministry of External Affairs, 2012), <https://mea.gov.in/Portal/ForeignRelation/China-January-2012.pdf> (Accessed on 26 October 2017)