The following article was part of The Gateway of India Dialogue 2016 compendium ‘Where Geopolitics meets Business‘. This piece has been published separately.

The Gateway of India Geoeconomic Dialogue will happen on 13-14 February 2017.

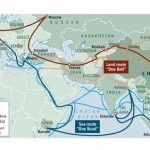

China’s geo-economic initiatives present India with a dilemma. While India wants Chinese investment, it is also aware that infrastructure initiatives such as One Belt, One Road (OBOR) have the potential to “redraw Asia’s geopolitical map” as Brahma Chellaney has put it. [1] Although India has expressed skepticism about OBOR, it has—unlike Japan or the U.S.—become a founding member of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), which will finance OBOR projects. But in order to balance Chinese influence in the bank, India will need to work with others, in particular with European countries.

The strategic context in Asia now looks somewhat different from the one described by the American analysts Evan Feigenbaum and Robert Manning in an influential article [2] published in 2012. They argued that two Asias were emerging: an “economic Asia” centered on China and based on a win-win logic of cooperation and integration and a “security Asia” centered on the U.S., based on a zero-sum logic of competition and disintegration. They wrote that “economic Asia” could become “an engine of global growth”, while “security Asia” could, in the worst-case scenario, lead to great power war.

In the four years since the article was written, however, the two Asias—which Feigenbaum and Manning argued were “increasingly irreconcilable”—seem almost to have merged. While military spending continues to increase throughout Asia and some speculate about an arms race, economic tools are now also increasingly being used for strategic purposes. What looked like two Asias with quite different dynamics now looks more like one complex Asia in which economic as well as military power are being used within a competitive logic between states.

And connectivity, India’s Foreign Secretary Subrahmanyam Jaishankar said in recognition of this new reality at the Raisina Dialogue in New Delhi in March, “has emerged as a theatre of present day geopolitics.” [3]

There are precedents in history for this kind of strategic development of infrastructure. Perhaps the most compelling comparison is the Berlin-Baghdad railway, which too was seen as a new Silk Road. The plan, initiated by Kaiser Wilhelm II at the beginning of the 20th century, was to create a link between Berlin and Mesopotamia—then part of the Ottoman empire—and eventually the Persian Gulf. The railway would cut the time it took to transport raw materials for Germany’s rapidly growing industry, and also displace British influence in West Asia.

The comparison fits into what Edward Luttwak—who first formulated the concept of “geo-economics”—has called the “inevitable analogy” [4] between Wilhelmine Germany and contemporary China. Just as Germany sought to compete with Britain, at the time the pre-eminent maritime power, China is now seeking to compete with the U.S.

China presents its geo-economic initiatives as a “win-win” or as public goods. It is tempting for countries in Asia that need infrastructure of the kind promised by OBOR, and the investment promised by the AIIB, to take Chinese rhetoric at face value. But they are well aware that China’s initiatives also have the potential to change the balance of power in Asia by creating relationships of dependence. As Jaishankar put it, while India wants to develop connectivity through a process of consultation, “others”—by which he clearly meant China—“may see connectivity as an exercise in hard-wiring that influences choices.”

In some respects, nearly all countries in the Asia-Pacific region face the same dilemma. With the exception of Pakistan and North Korea, they see the rise of China simultaneously as an opportunity in economic terms, and also as a threat in security terms. But China’s geo-economic initiatives also have the potential to divide Asian countries among themselves. It is not just that some countries are closer to the U.S. than others, but also that, based largely on geography, they differ in how they view the two parts of OBOR. While some feel more threatened by the Silk Road Economic Belt, others feel more threatened by the Twenty-First Century Maritime Silk Road.

Both the “belt” and the “road” are a potential threat to India. It is particularly alarmed, of course, by the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which seems to be intended to link the two parts of the project—and thus in effect to encircle India. As a result, some such as Chellaney even see OBOR as a reincarnation of China’s “string of pearls” strategy. [5] Even more problematically from an Indian point of view, CPEC passes through Pakistan-occupied Kashmir. India may be less dependent on the Chinese market than some other countries in the region, but it too wants Chinese investment—in particular to develop its manufacturing sector.

India’s ambivalence has so far been manifested in its slightly different approach to the AIIB on the one hand and OBOR on the other—even though the AIIB is meant to fund projects that are part of OBOR. India has been skeptical of OBOR, which it sees as a national rather than an international or regional initiative. But it nevertheless agreed to be a founding member of AIIB and is the second-largest shareholder, with 7.5% of the voting rights. Perhaps like EU member states that joined the bank, India’s aim is to influence the AIIB from within. India successfully pushed for the AIIB’s Articles of Agreement to include a requirement that the financing of projects in disputed territory can only proceed if the disputants provide their consent.

In order to continue to influence the AIIB and through it OBOR, though, India will need allies. Collectively, Europeans have around 20% of the voting rights. Since China has 26% percent of the voting rights, Europe and India could balance Chinese influence in the AIIB were they to cooperate. But whether the EU and India will be able to do so depends on whether they can develop a shared agenda.

Europeans instinctively share India’s preference for multilateral rather than unilateral approaches to connectivity. But even though the precedents for China’s geo-economic initiatives lie in their own history, Europeans tend somewhat naively to take at face value Chinese rhetoric about their “win-win” nature. India still has a way to go to make Europeans see OBOR from an Indian perspective.

Hans Kundnani is a Washington-based Senior Transatlantic Fellow at the German Marshall Fund of the United States. He was previously the Research Director at the European Council on Foreign Relations, London.

The Gateway of India Dialogue was co-hosted by Gateway House and the Ministry of External Affairs on 13-14 of June 2016. The 2017 conference, The Gateway of India Geoeconomic Dialogue will be held on 13-14 of February 2017.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2016 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited

References

[1] Chellaney, Brahma, ‘A Silk Glove for China’s Iron Fist’, Project Syndicate, 4 March 2015, <https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/china-silk-road-dominance-by-brahma-chellaney-2015-03?barrier=true>

[2] Feigenbaum, Evan. A., and Robert A. Manning, ‘A Tale of Two Asias’, 31 October, 2015, <http://foreignpolicy.com/2012/10/31/a-tale-of-two-asias/>

[3] S. Jaishankar, Raisina Dialogue, speech delivered at Raisina Dialgoue, 2 March 2016 <http://mea.gov.in/Speeches Statements.htm?dtl/26433/Speech_by_Foreign_Secretary_at_Raisina_Dialogue_in_New_Delhi_March_2_2015>

[4] Luttwak, Edward. N, The Rise of China vs The Logic of Strategy (Belknap Press, Harvard University Press: Boston), 2012.

[5] Kazmin, Amy, ‘India watches anxiously as Chinese influence grows’, Financial Times, 9 May 2016, <http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/e9baebee-0bd8-11e6-9456-444ab5211a2f.html%23axzz48Y6T7pzn>