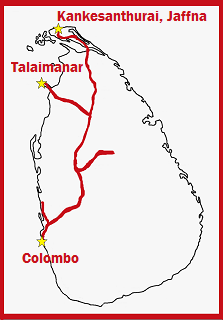

On October 13, Sri Lankan president Mahinda Rajapaksa launched the final 38-kilometre northern stretch of the railway line between Jaffna to the capital Colombo. The Indian High Commissioner, Y.K. Sinha, who participated in the inauguration ceremony, said the resumption of the service after a 24-year disruption will promote “development, reconciliation and greater integration by bringing people in different parts of the island closer.”

The railway has connected the two cities since 1905, but many of the northern sections of the track were destroyed by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) during the 1982-2009 civil war. The Indian Railway Construction Company, run by the government of India, has repaired those sections of the 400-kilometre train track, financed by an $800 million soft line of credit—announced in 2010—from India.

More than 40,000 civilians were killed—according to United Nations estimates—by the Sri Lankan army and the LTTE during the civil war. Western countries did little to curb the flow of funds to the LTTE from their expatriate Sri Lankan Tamil communities. But they have censured the Sri Lankan government at the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC) every year since 2011, when a resolution was introduced by the U.S., for the violations of human rights in the final days of the war.

India decided instead to focus on rebuilding infrastructure and homes in the Tamil-majority Northern Province in order to address the needs of local Tamils. To do this, it has to work with—and not constantly be at odds with—the Sri Lankan authorities. At the same time, India has urged the Rajapaksa government to implement the recommendations of its own Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission (LLRC), which was set up to investigate allegations of numerous well-documented violations against innocent civilians caught in the crossfire between the army and the LTTE.

But the efficacy of the strategy of rebuilding is being challenged by the elected representatives of the Sri Lankan Tamil community. The chief minister of the Northern Province, C.V. Vigneswaran, and the five-party Tamil National Alliance, boycotted the inauguration of the railway to express their resentment against India and the Sri Lankan government—in particular, at India’s failure to pressure Rajapaksa to implement the 13th Amendment (passed in 1987) to the Sri Lankan Constitution. The amendment provides for the enhancement of the powers of the provincial councils in the North and East, including powers over the police force and land use.

Sri Lankan Tamils have regarded India as an ally since the enactment of the Sinhala Only Law of 1956, when the first measures against the use of the Tamil language, and the disadvantaging of the Tamil community, began to be enacted. The Tamil cause, always popular in Tamil Nadu, continues to be supported by India, which has counselled successive Sri Lankan governments against alienating the community. The culmination of these efforts was the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord of 1987, which paved the way for the 13th Amendment.

No country has a greater stake than India in ending the legal and political discrimination against Tamil-origin Sri Lankans because of the resonance of their concerns, especially in Tamil Nadu. Unfortunately, the issue has been cynically turned into an emotive tool in Tamil Nadu politics. This has circumscribed the options available to New Delhi.

Although the government of India has vacillated in its voting at the UNHRC over the West-sponsored censure of the Sri Lankan government, it has resolutely prioritised the rehabilitation of the infrastructure of the Northern Province. India is engaged in projects worth over $1 billion in the North and East. This includes a $270 million commitment to build 50,000 housing units across affected areas, the rehabilitation of Kankesanthurai Harbour, Palaly Airport and Duriappah Stadium in Jaffna, and building a 500-megawatt coal power plant at Sampur in the Eastern Province.

But China has funded and is executing even larger projects across Sri Lanka, worth nearly $5 billion. These include the expansion of Hambantota Harbour, the Puttalam coal power project, the Colombo-Kattunayake expressway, and the Matala Rajapaksa airport.

Colombo’s importance to Beijing was reiterated during President Xi Jinping’s visit to Sri Lanka in September, when he inaugurated the construction of the $1.4 billion Colombo Port City—a commercial centre off the coast—located conveniently near the $500 million Chinese-built Colombo International Container Terminal.

As historic friends and neighbours, India and Sri Lanka have many points of strategic convergence, such as their shared concern about terrorism emanating from Pakistan. In 2009, a bus carrying the Sri Lankan cricket team to a match in Lahore was attacked by terrorists, killing six police personnel and two civilians, and injuring many others. Colombo has taken action against suspected Pakistani terrorists pretending to be asylum seekers and trying to enter India from the south. This is an important step in expanding regional cooperation on combating terrorism.

However, despite converging strategic and economic interests, including annual bilateral trade worth $3.7 billion, and despite appeals by numerous Tamil Nadu-based political parties, India cannot apply too much pressure on Colombo to mitigate the discrimination against Sri Lankan Tamils. India’s options are especially limited because it cannot ignore the importance of close relations with the Sri Lankan government in the strategic landscape of South Asia—which is evolving with the economic rise of China and its expansionism in the Indo-Pacific region.

Meanwhile, Rajapaksa has sought investment and infrastructure assistance from India as well as China, and has managed to deftly balance his country’s strategic importance to both countries. The absence of effective political opposition in Sri Lanka—Rajapaksa’s family members occupy senior positions in government, the opposition is disorganised, and opponents like former General Sarath Fonseka, who contested the 2010 presidential elections, are in jail—gives Rajapaksa greater latitude to keep a diplomatic and developmental equilibrium with India and China. To cement his grip on Sri Lanka, he has called for elections in January 2015, a whole two years ahead of schedule.

India, too, has its own balancing act to perform, torn as it is between pushing Colombo to implement the 13th Amendment as well as the recommendations of the LLRC report of 2011, while it tries to retain its influence and economic interests in Sri Lanka.

Steps in the right direction for India can include finalising the long-delayed Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement with Sri Lanka to promote economic integration. India must also expedite pending projects, particularly the housing project—at the end of 2013 only 10,250 new homes of the target of 50,000 were completed.

Measures such as these can help India counter China’s growing affinity with Colombo. When Prime Minister Narendra Modi visits Kathmandu for the 18th South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) Summit in November, he will have to find ways to check China’s expanding influence in all SAARC countries.

Ambassador Neelam Deo is Co-founder and Director of Gateway House. She has been the Indian Ambassador to Denmark and Ivory Coast with concurrent accreditation to several West African countries.

Karan Pradhan is a Senior Researcher at Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2014 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.