The joint statement signed between Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chancellor Angela Merkel, during Modi’s April visit to Germany articulated a desire to enhance the existing cooperation in the field of skill development and chart a road map to increase employability of trainees and apprentices. For India to do so, the biggest challenge will be to equip its populations with the necessary training and skillsets. India and Germany have been strong partners in the field of development cooperation, exemplified by the establishment of a bilateral working group in 2008 to promote the German-pioneered ‘dual system’ of Vocational Education and Training (VET).

This system is a part of the German education system and is considered one of the major reasons for the competitiveness of its manufacturing sector. Students commence training upon completion of high school and the courses span two to three years. ‘Learning by doing’ is the cornerstone of the system as it combines hands-on practical exposure with theoretical study. Through this mechanism, students graduate with a university degree and substantial work experience in their field of interest. The apprenticeship offers 350 occupations covering diverse fields. In order to make the model feasible, Germany relies on government funding for the schools whereas corporate institutions provide skill training and job experience.

Due to the system’s success, it has been implemented in several countries like Austria, Switzerland, Netherlands, France, and more recently China. Studies have shown that countries with dual VET systems have resulted in the successfully tackling the problem of youth unemployment.

Vocational training in India

India’s demographic dividend presents both opportunities and challenges. An average Indian will be 29 years of age by 2020, in comparison to 37 in the U.S. and China, 45 in Europe and 48 in Japan. While this will put India at an advantage with one of the world’s youngest working populations by 2020, it will need to equip its population with the necessary skills to work.

Acknowledging the need to restructure India’s VET system, the Government of India notified the formation of the Department of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship on July 31 2014. This led to the formation of the Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship on November 10, 2014.

Under the formal education system, vocational education is offered after secondary school in Classes 11 and 12. Alternately, vocational training takes place through institutions that are outside the school system. Such institutions are usually government or private industrial training centers.

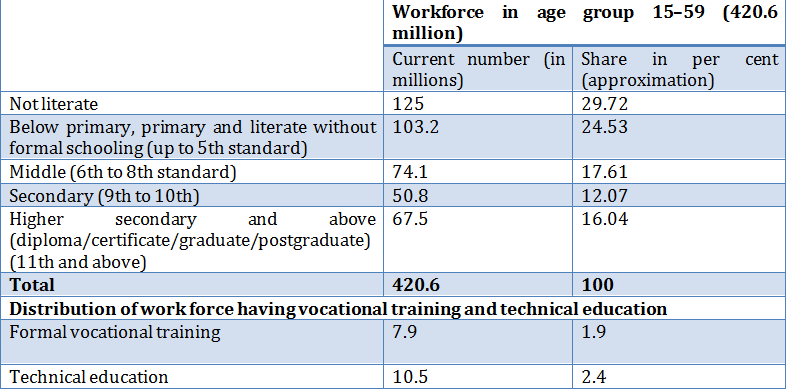

However, a large percentage (almost 50%) of India’s workforce is either illiterate or with primary/less than primary education. In 2009-10, out of the total workforce of 460.2 million, only 50.8 million received secondary education, 7.9 million received vocational training and 10.5 million received technical education. As seen in Table 1, 228.2 million people of the workforce were either completely illiterate or with primary/less than primary education.

Table 1: Education and Training of those in Workforce, 2009–10

Twin Challenges

The government is faced with a two-fold challenge in terms of the VET systems functionality. As eight years of schooling is a prerequisite to receive vocational training, the first challenge is that half of India’s current workforce requires functional literacy. The government therefore needs to ensure that children between the ages of six and 14 years receive education (as secured by the Right to Education Act that came into force on April 1 2010).

The second challenge is the ‘skills gap’ in India in terms of the demand and supply of a skilled workforce. In order for the government to further its development agenda of accelerated economic growth there is an urgent need for human capital development in order to bridge this gap between the quality and quantity of India’s human capital.

India has already proposed ambitious medium and long-term targets for skill development, with a target of 500 million skilled workers by 2022. However, the existing annual training capacity in the country is only 4.5 million per year.The VET system in India is not equipped to meet industry requirements and needs. The centres receive little funding and due to the lack of incentives they remain of poor quality, receive low corporate support and insufficient youth participation.

Plugging this gap the German way

India and Germany differ in terms of the structure of their economies, the stage of industrial development and the size of informal sectors. In practice, there are vast differences between the Indian and German VET models; however there are many features that may be implemented in order to reorient the Indian system:

Dual system: The German VET consists of state-run schools that provide the formal theoretical knowledge whereas practical exposure is acquired through private companies. The Indian model lacks the flexibility to offer such exposure. The integration of work and study can prove to be a beneficial factor.

Curriculum coordination: Designing the course structure in order to substantiate the practical exposure is necessary. In India the curricula are developed by the government. A more integrated approach that allows the participation of all relevant stakeholders would increase the credibility of the model.

Funding and feasibility: Companies are the final beneficiaries of skilled workers. Joint funding of education and training would allow the model to be feasible. It would assure quality, as the companies would look to maximize the return on investment.

Legalisation of such a model, developing the methodology for training the trainers and creating a relevant curriculum would be the major challenges of such a system. However, altering the model to suit Indian requirements may be the key to developing the potential of India’s human capital and reach India’s ambitious growth agenda.

Under Modi’s leadership, India has already begun reshaping its vocational training system. It remains to be seen whether the upcoming National Policy on Skill Development and Entrepreneurship 2015 will bring about the much-needed changes.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.

© Copyright 2015 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.