This feature was originally written for Where Geopolitics Meets Business, Vol. 2, the compendium for The Gateway of India Geoeconomic Dialogue.

The Belt and Road Initiative (B&RI) or New Silk Road is the ambitious centrepiece of China’s strategic geopolitical and geoeconomic initiative.[1] This resurrection of the ancient Silk Road, the longest road known to mankind, is being shaped by Chinese President Xi Jinping’s vision (first articulated in September-October 2013), of a resurgent One China in the marketplaces of Eurasia, Europe, and the world.

The Belt and Road Initiative is so expansive, multi-layered—covering road, sea, rail, financial, energy and digital corridors—and hegemonic in its embrace, powered as it is by Chinese finance and infrastructure build-outs, that it obliterates the cosmopolitan nature and multilateral trade history of its template, the Old Silk Road.

Hence, there is an urgency to understand the pre-European history of the Silk Road, how it coalesced, when it was named, and how it facilitated trade. This knowledge has lessons not only for China, but all countries participating in the New Silk Road, and will, when the time is right, provide a context for India’s participation in this grand act of Asian inter-connectivity.

Trans-Asian routes and a name

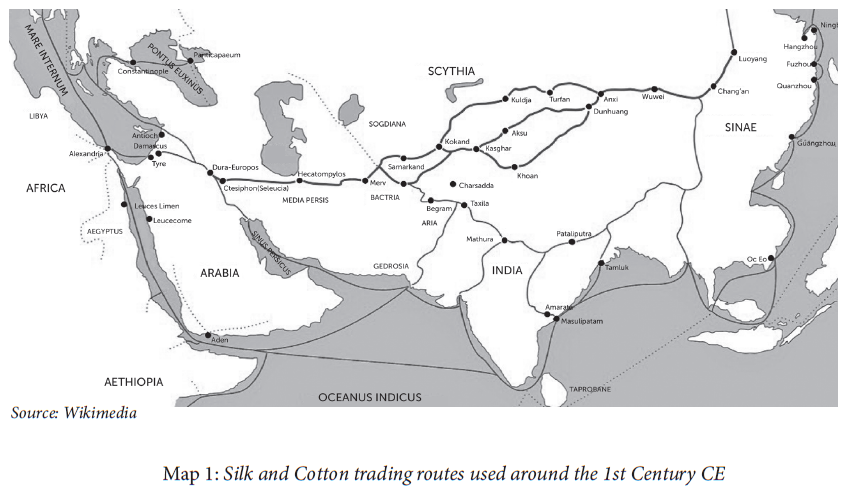

The origin of the name ‘Silk Road’ is relatively recent. In ancient times, during the Early Han Dynasty (206 BCE to 25 CE ), contemporaneous with the powerful Mauryan Empire (322 to 183 BCE) and the Kushans (2 BCE to 3 CE) in the Indian subcontinent, the Parthians of Persia, and the ancient Roman Empire, this road comprised of a network of shifting caravan routes that connected one market town, often an oasis, to the next. In its east-west axis, it covered 7,000 km from Xi’an (ancient Chang’an) to its western termini in present-day Cadiz (then Gades) in Spain. Interestingly, this east-west axis road never had a name: instead sections of the route were named quite romantically after the market town they led to, such as, ‘the road to Samarkand’.[2]

The name ‘Silk Road’ was coined in 1877 by the German baron, Ferdinand von Richthofen, a geologist who worked in China from 1868 to 1872, surveying coal deposits and ports. It was his five-volume atlas, which, in map 2-3, shows the route during Roman times, and for the first time, as a trunk road, resembling a straight railway line cutting through Eurasia, and not a network of caravan routes. It was speculated then that the baron’s survey was actually a mapping for a possible German railway line.[3][4]

It was subsequent to this naming that the collective term—Silk Road—gained currency.[5] A negative fall-out of this was the erasure of these trans-Asian caravan routes: how they evolved constitutes a history of collaboration between regional kingdoms, local traders (in ancient times, Parthians, Sogdians, Indians, Chinese) and itinerant merchants. This network of routes functioned very much like the logistics corridors of e-commerce firms today, where traders from each region acted as aggregators and formed caravans that carried goods over a specific length of the road.

The name ‘Silk Road’ also led to the misconception that Chinese silk was the only reason why the route that was formed by 1 CE assumed priority becasue of its procurement for the ancient Romans.[6]

The truth, however, is more nuanced. It was much later during the Tang dynasty (618 to 907 CE), a period when trade flourished along these trans-Asian overland routes (due to a strong Tang kingdom), that silk pervaded the markets along the roads as Chinese soldiers, posted to secure the route in the newly annexed north west (a part of modern Xinjiang province), were paid in bolts of silk rather than in grain or bronze coins.

The cotton road to the Indian subcontinent

How does all this connect to the Silk Road trade in Indian cotton, also a valuable commodity in the pre-European commercial transactions conducted via these road and sea networks?

Not many are aware that the Old Silk Road has a southern axis.[7] This comprises routes into the Indian subcontinent via the Chinese province of Xinjiang to Kashmir (the China Pakistan Economic Corridor uses this road). There is the Khyber Pass route too,[8] used by Chinese Buddhist monks Fa-Hien (who travelled from 399 to 414 CE) and Hsüang-tsang (629-645 CE), a route that connects Balkh (northern Afghanistan) to Kabul, and from west Yunnan (a province in south west China) into Bangladesh, Assam and Myanmar.

One of the earliest written records on the Silk Road is Records of the Great Historian (compiled by Sima Qian in 1 BCE), written 150 years after the first two Chinese diplomatic missions into Central Asia, led by imperial envoy Zhang Qian during the 2nd BCE. He had been sent by Han emperor Wu to muster support from the Yuezhi people (then settled in the Fergana region of modern Uzbekistan) to ally with the Chinese against their common enemy to the north, the Xiognu tribes from Mongolia.

His details of South Asia are significant, as trade routes in this region were already well-worn and were conduits for the export of cotton products from the subcontinent to Central Asia, China and Rome.

This was a time when the Chinese did not grow cotton and Indians did not know how to manufacture silk (by 5th CE they produced a silk called kauseya). Even when guilds of silk manufacturers were established in the subcontinent and cotton weaving centres came up in Central Asian towns, like Khotan (Xinjiang), both simultaneously by the 5th CE, there was always a demand for high quality muslins from Bengal (mentioned in Tang records) and cotton piece goods from Gujarat and the South.

Cotton growing and manufacturing spread from northern and peninsular India from the 1st to 5th CE to Myanmar and South

East Asia through conquest, trade and cultural linkages. This region (comprising present-day ASEAN), and the subcontinent, supplied cotton items to imperial China through the overland and maritime routes, which were well established by the 8th century CE.

That there existed an active Indo-China trade in cotton cloth is also borne out by Ma Huan, the chronicler of the seven Ming voyages (1424-1433 CE), led by the imperial Admiral Zeng He, who lists out six varieties of Bengal cotton (including the renowned Dacca muslins), and one from the south.[9]

The spread of Buddhism from India to Central Asia, China, Sri Lanka and South East Asia, further increased the demand for cottons: Buddhist monks practised the doctrine of ahimsa (non-violence), which forbade the wearing of silk, as its manufacture requires boiling mulberry cocoons and killing the silkworms within in order to draw out silk thread.

Indian cotton and Chinese silk remained valuable components of the Silk Road trade that flourished between two ancient civilisations for two millennia. It is this history of inter-dependence—when silk roads were cotton roads and vice versa—which underscores how integrated these two regions were, in fact, Asia itself was, before European intervention. History illustrates that the longest road known to mankind functioned because of a combination of elements—part geography, part politics and part people—but the overriding factor was its inherent multilateralism, where roads were built, maintained and secured not just by empires, but small, independent oasis towns and regional kingdoms.

Perhaps China’s B&RI initiative will be more successful were it to infuse this spirit of co-operation into the enterprise. Co-opting India into this vast Eurasian grid will be a coup d’état as not only is it the second largest economy in Asia, but historically, the original home of Buddhism and cotton goods, both hallmarks of the Old Silk Road.

Sifra Lentin is the Bombay History Fellow at Gateway House. She has been published in MARG’s Indian Jewish Heritage: Ritual, Life-Cycle & Art (2002); she has also written a book for the Indian Navy’s Western Fleet, titled A Salute To The Sword Arm: A Photo Essay On The Western Fleet (2007).

The Gateway of India Geoeconomic Dialogue was co-hosted by Gateway House and the Ministry of External Affairs on 13-14 of February 2017. For more details on the event please click here.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2017 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited

References

[1] The New Silk Road Initiative and its counterpart the 21st Century Maritime Silk Route are commonly referred to also as One Belt One Road (OBOR).

[2] Hansen, Valerie, The Silk Road: A New History (New York, Oxford University Press, 2012), pp. 175.

[3] Ibid, pp. 176.

[4] The period when Baron Richthofen worked in China was a time when Europeans (British, French, Germans), the Russians, and later the Japanese, were all competing for influence in a financially weak, imperial China, wracked with internal dissensions. The Baron was charged with mapping a direct railroad from the German sphere of influence in Shandong province via the coalfields near Xi’an, to Germany.

[5] The German name Die Seidenstrasse translates to ‘the Silk Road’. <en.unesco.org/silkroad/about-silk-road> Accessed on 24.1.2017.

[6] Hansen, pp 209.

[7] The southern roads also encompass the Iranian plateau, the Tigris and Euphrates valley, and West Asia. More pertinently for the Indian subcontinent there exist two well delineated branches of the Silk Roads, namely Uttarapatha (the northern or Gangetic plain route) and Dakshinapatha(southern route). <http://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5492/> Accessed on 26.1.2017.

[8] Tansen Sen, ‘The Travel Records of Chinese Pilgrims Faxian, Xuanzang, and Yijing’ , Education About Asia, Volume 11, 3, Winter 2006, <https://web.archive.org/web/20140713172856/http:/www.form.og/tours/ChinesePilgrims.pdf>

[9] Dale, Stephen F., ‘Silk Road, Cotton Road or…Indo-Chinese Trade in Pre-European Times’, Modern Asian Studies, Volume 43, Issue 1, pp 83, 2009, pp 83.