The Bubonic Plague epidemic of 1896 lasted 20 years, it brought the city of Mumbai (then Bombay) to a grinding halt and decimated its population. By October 1896, 20,000 people had fled the city, and by February 1897, the population had halved to 450,000 people from 846,000 3 months back.[1] At its peak, from 1897 to 1901, the number of plague related deaths averaged a staggering 2624 per week.[2] Never had ‘Bombay the beautiful’, as one newspaper at the time commented, looked so deserted.[3] Today, over a century later, Mumbai, with its empty roads and absence of commerce (except for essential services) wears the same pallor of gloom and anxiety that it once did, during what will now always be remembered as the ‘Bombay Plague’.

The name ‘Bombay’ was attributed to this epidemic not because the city was its geographical origin, but because its devastation in terms of human life, health, property and livelihood were the greatest at its entry point of Bombay and its Presidency (which included other hotspots such as Poona and Karachi). In the 20 years that the epidemic ravaged the Indian subcontinent, it is believed that over 8 million people lost their lives to it.

A prospering city

Unlike Covid19, which is a virus, the plague was caused by a zoonotic bacterium, carried by a rat flea, which is suspected to have entered Bombay sometime in August-September 1896, on board the ship Mandarin that arrived from British Hong Kong. Hong Kong was then in the throes of an outbreak.[4] At the time of onset, Bombay was not just the financial capital of British India but also a thriving international port and a major manufacturing center for cotton yarn and textiles. The revenue that the city and its Presidency generated was a sizeable chunk of the annual home payments sent to Great Britain. Not much has changed today in terms of the city’s importance in governance revenues. It remains an integral financial capital of India and a major contributor to the center’s tax coffers. It is also one of the most impacted by Covid19.

By 1896, there was already a use of stringent sanitary measures by colonial civic officials in Bombay, because of the recurring small-pox, cholera, diphtheria[5] and fever outbreaks. All of these were blamed on the unsanitary lifestyles of the local population. The death of Lady Fergusson (wife of Bombay Governor, James Fergusson) from cholera in Parel House (present day Haffkine Institute) in 1883, had a profound psychological effect on the resident British population[6] as it drove home the fact that they and their families could also get infected. The increasing xenophobia, peaked with the plague outbreak, and determined the manner in which anti-plague protocols, later enacted by the Epidemics Act of 1897, were implemented.

It wasn’t necessarily the stringency of the measures, which by all accounts seemed to have been warranted just as the all-India lockdown is today, but the tenor in which they were enforced that led to either acceptance or outright revolt. From the very beginning, it was clear that tracking the infected and those who had come in contact with them was the first step to breaking the cycle of infection particularly for the more virulent pneumonic variety where the plague bacillus was carried in droplets of air, much like the Covid19 virus is today. Though killing rats (carriers of the flea) was a major part of the city’s clean-up, contact tracing and quarantining people in Plague Camps were active measures (just as they are today) to check the spread of infection.

Tracking down cases

The first plague case in Bombay was diagnosed by Dr. Acacio G. Viegas[7], when he visited a patient in Mandvi on 23 September 1896. It is significant that the outbreak began in Mandvi, an area close to the docks and home (even today) to warehouses, grain merchants and dense, crowded dwellings. This first case was a bubonic plague case, however, its variant the more infectious pneumonic plague,[8] also appeared simultaneously in the city. It was the population density of the Mandvi area, very much like the slums of Dharavi (a Covid19 hotspot today), which encouraged contamination and spread.

Initially, the tracking, detection and sequestering, was implemented by the Bombay municipality and its locally elected officials who were naturally sympathetic, and attuned to local sensitivities. However, a death toll of 33,161 people from September 1896 to March 1897 called into question their competence,[9] and even whether Indians were really fit for self-governance to begin with.

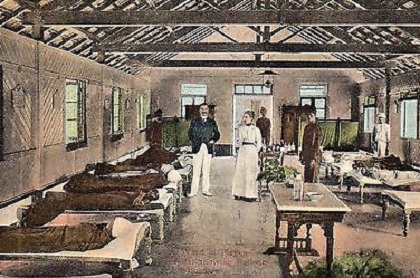

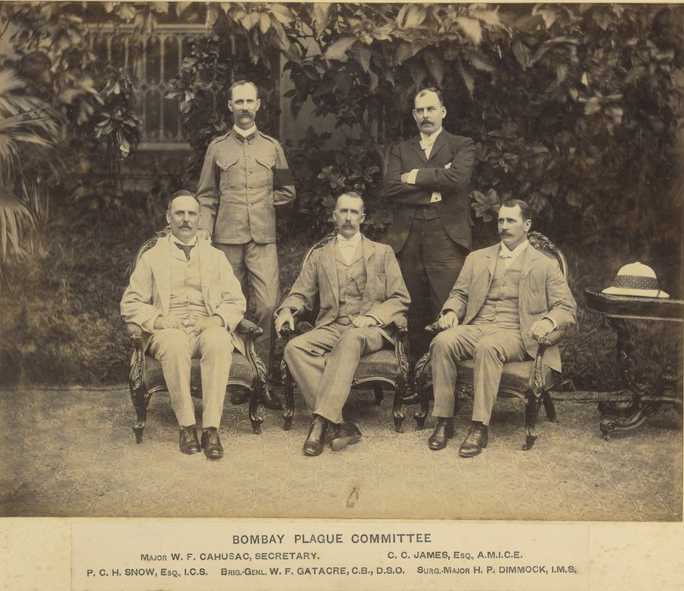

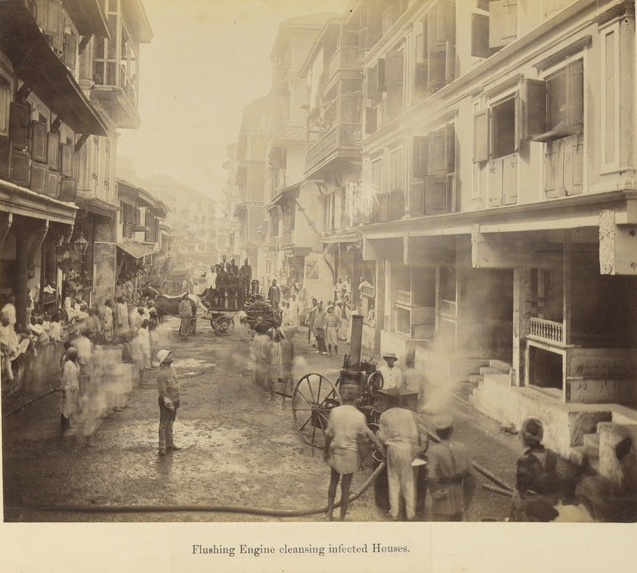

In March 1897, the British Indian government formed all-European Plague Committees to enforce control and sanitation[10]. The extreme measures taken by these committees against the local population led to a strong backlash in the local press, especially regional language newspapers such as Bal Gangadhar Tilak’s Maratha. Teams of soldiers and local volunteers forcibly entered homes of victims, burned beddings and personal belongings, broke the roofs and sanitised the confines. The house was then marked UHH (unfit for human habitation). The victim, often in a moribund condition, was forcibly carried away to a plague hospital with low survival rates.[11]

The measures were culture and gender insensitive and sacrilegious at a time when strict social distancing was observed between castes and communities. A flashpoint was reached when Walter Rand, chairman of the plague committee in Poona and his military escort were shot dead in June 1897 as an act of protest.[12]

The unpopularity of plague controls (in the first wave of the outbreak) combined with the panic created, was a stimulus to an unprecedented flight of migrant labour out of the city to their villages. They carried the infection unwittingly through carrier fleas on their clothes and beddings. It wasn’t just the mill workers but the freight trains carrying goods out of the city that were also culpable in the spread of plague across India.

In 1896, Bombay and its Presidency had 133 cotton mills and the large-scale exit of its mill operatives and dock workers severely impacted the city’s economy. In order to keep the mills humming, there was an open and cut-throat bidding by mill agents for labour on street corners. Not only were wages unreasonably high but the system of daily wages was introduced, with no guarantee of workers reporting the next day for duty.

It was only in 1905-06 that the city’s textile industry became solvent once again, with the return of its migrant work force, many of who by now preferred to risk the plague than face starvation in their villages. [13]This return migration is likely in the Covid19 situation we face now and may happen simultaneous to the staggered starting-up of the economy.

In the past, what finally helped control the Plague epidemic was the discovery of a vaccine in 1897, by Dr. Waldemar Haffkine, who single-mindedly worked on it and was the first to test it on himself on 10 January 1897. A dogged pursuit of a vaccine and widespread inoculation might be the best possible solution to curtail the spread of Covid19 as well, as long as the virus doesn’t keep mutating.

A new urban vision

By 1900, there was a shift in thinking by the British on how to tackle the epidemic, resulting in a relaxation of controls. First, the violent backlash to plague protocols, which peaked with Rand’s assassination and the fact that the death rates were still high led to a policy of “co-opting” rather than “subjecting” people to controls. This was undertaken by reaching out to community and political leaders.

A positive and direct fallout of the Bombay Plague was the creation of a Bombay City Improvement Trust in November 1898 to decongest the city. It was the work of this trust that created the north-south Mohammed ali Road, and the east-west Princess Street and Sandhurst Road corridors with the aim of cross-ventilating the old city areas. It also created expansive garden housing estates, such as the Hindu and Parsi colonies in Dadar, in order to decongest south Bombay. Even today, in the times of Covid19, accelerating the redevelopment of slums, in particular Dharavi, has acquired a renewed urgency.

It is no doubt that Mumbai and India post Covid19 are going to be indelibly changed now as they were after the Plague over a century ago. Today, as the country grapples with curtailing a new pathogen, its government and citizens should learn from the mistakes and successes of the past to plan for the future.

Sifra Lentin is Bombay History Fellow, Gateway House.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in

© Copyright 2020 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References

[1] Ramanna, Mridula, Health Care in Bombay Presidency 1896-1930 (New Delhi, Primus Books, 2012), p. 13.

[2] Edwardes, S.M., The Gazetteer of Bombay City and Island Volume III (Pune, The Government Photozinco Press, Reprint 1978), p. 175.

[3] The regional newspaper Kaiser-i-Hindmade this observation in its issue dated 17 January 1897. Ibid (i), p.13.

[4] Catanach, I.J., The Globalization of Disease? India and the Plague, Journal of World History (University of Hawaii Press), Volume 12, No. 1, pp. 135. This journal article states that the plague was present in British Hong Kong in 1894, a few cases were reported in 1895, and many more in 1896. Also, Kalpish Ratna, Room 000: Narratives of the Bombay Plague (New Delhi, Pan Macmillan, 2015), p25.

[5] Ramanna, Mridula,Coping with Epidemics: Indian Responses, Bombay Presidency, 1900-1919, in Bandyopadhyay, Arun, ed, Science & Society1750-2000(New Delhi, Manohar, 2010), pp. 145-167.

[6] Parel House, the Bombay governor’s residence since 1829,ceased to be Governor’s Houseafter Fergusson’s tenure ended in 1885. Subsequent governors shifted to the breezier Governor’s House (today’s Raj Bhavan) at Malabar Point. By a twist of fate, Parel House became the city’s first Plague Hospital during the years 1897-98, before the Plague Research Laboratory headed by Dr. Waldemar Haffkine shifted there in 1899.

[7] Dr. Acacio Gabriel Viegas was a Goan doctor, who first alerted the city’s municipal corporation to the outbreak of plague. He was later president of the Bombay Municipal Corporation and a municipal councilor for many years. His statue stands in Dhobi Talao facing Metro Theatre.

[8] The pneumonic plagueaffected the lungs and was more virulent as it was transmitted through droplets in the air, while the bubonic variety, identified by a bubo near the groin, was less infectious.

[9] Ramanna, Mridula,Health Care in Bombay Presidency 1896-1930 (New Delhi, Primus Books, 2012), p. 11.

[10] The Epidemics Act (1897) resulted in financial control over plague expenditure being taken out of the hands of the Bombay Municipal Corporation and being vested first in a Plague Commissioner. A few years later, when the Plague Committees were disbanded the Municipal Commissioner was appointed as the plague administrator.

[11] Often the victims were dying by the time they were taken to the hospital as a result the death toll in the hospitals were very high, which led to misinformation that the hospitals killed the patients. This in fact led to an attack on the Arthur Road Hospital on 29 October 1896 by 800 to a 1000 people. It was an attack on medical personnel. See, Ramanna, Mridula, Health Care in Bombay Presidency 1896-1930 (New Delhi, Primus Books, 2012), p. 20.

[12] Bombay too, witnessed its share of hostility towards anti-plague measures.On 9 March 1898, riots occurred in Madanpura when a medical team and plague officer of the ward, were refused admission into a house to examine a suspected plague case.The crowds attacked them and in the subsequent police firing five persons were killed

[13] Many mill operatives began returning to the city after just a few months. The outbreak of plague in 1896 coincided with famine, which saw large numbers of returnees afflicted with diseases likecholera re-entering the city.