On 4 Jun 2020, amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, Indian Prime Minister, Narendra Modi and Australian Prime Minister, Scott Morrison held the first ever virtual summit between India and Australia. This summit was historic in more ways than the fact that it was virtually conducted. Among the many agreements signed between the countries, the Agreement on Mutual Logistics Support (MLSA),[1] is one of the most important, given the geo-strategic maritime competition between India and China. A critical aspect of the MLSA is both countries agreeing to share their military bases for refueling and logistics purposes, as well as to enhance military engagement and maritime domain awareness between the two countries.[2]

India has a Mutual Logistics Arrangement with many countries such as the U.S., France, Oman, Philippines, Indonesia (Sabang Port) and others. Logistics agreements are also planned with Japan and Russia. Most of these establish consensus on sharing logistics facilities such as fuel, bases and supplies when the militaries and their personnel interact with each other.

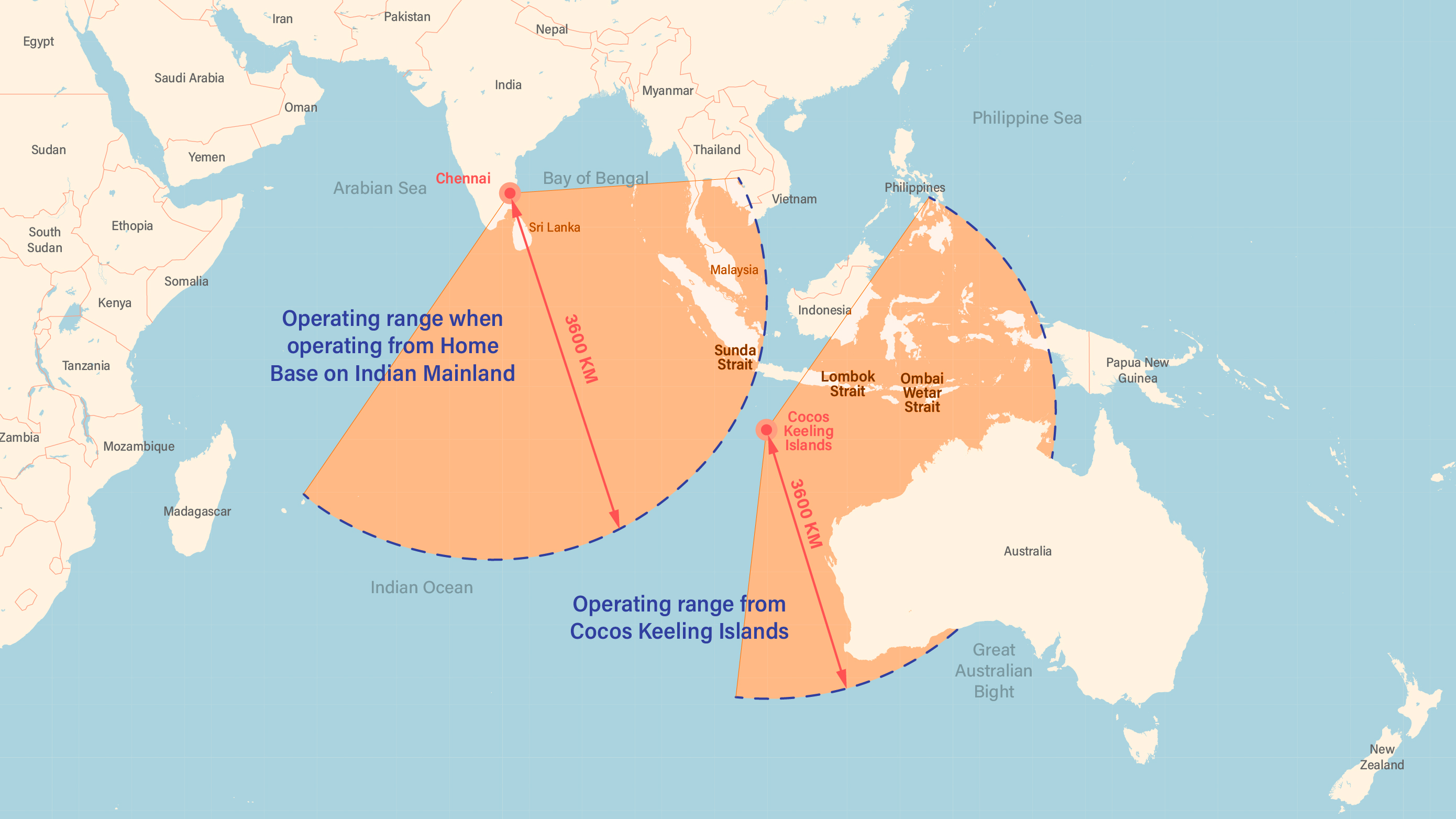

How is the MLSA with Australia any different or more consequential? For India’s defense interests, mutual logistics arrangements with like-minded nations have yielded greater returns for the Indian Navy, compared to any other service. The MLSA with Australia is especially significant because at an operational and tactical level, it enhances the reach and effectiveness of India’s naval assets in sustaining near-continuous deployments at eastern choke points to the Indian Ocean, such as the Sunda, Lombok and Ombai Wetar straits. These locations are otherwise almost at the edge of the range of India’s foremost maritime surveillance aircraft the P8I.[3] The P8I, part of Boeing’s Poseidon series, has a ‘loiter time’ capacity (to stay in the vicinity of a target), of four hours at about 2,000 km from its base. This loiter time is necessary for an aircraft undertaking anti-submarine missions.

Ever since India signed the LEMOA (Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement)[4] with the U.S. in 2016, the Indian Navy and its U.S. counterpart have used the arrangement to replenish deployed ships at sea. Indian naval ships on patrol in the Gulf of Aden regularly refuel with the U.S. naval tanker in the region. Reciprocally, U.S. naval ships have also taken fuel from Indian naval tankers in the Indian Ocean, on the western side. .

The agreement with Australia, promises to be different in some specific ways.

An enduring challenge for India has been the operational reach of its maritime air surveillance assets over the south eastern Indian Ocean, which is from where Chinese submarines enter the Indian Ocean. This has meant complex planning for prolonged deployments in the region. As seen in the map below , these choke points are more than 2,000 nautical miles (3,600 km) from mainland India.

The MLSA with Australia provides for reciprocal refueling capabilities in the Western Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf, and for Indian assets at Australian military bases. The Indian Navy will now be interested in undertaking P8I operations from Australian bases in the Cocos Keeling Islands (being developed by Australia) and the port of Darwin, both of which are close to the choke points. Operating from Northern Australian bases during exercises will provide Indian crews with enough ‘loiter time’ to develop expertise in underwater operations in those waters. This is critical for Indian naval operations considering that monitoring China’s submarine movements at the choke points is far easier than looking for them in the vast Indian Ocean, once they have crossed the choke point.

While P8Is can operate from Australian Air Bases, the visit of Indian Naval ships and submarines to the port of Darwin will be complicated. The commercial port of Darwin was leased in 2015, by the government of the Northern Territory, for 99 years, to Chinese Company, Landbridge Industry Australia, which is a subsidiary of the Shandong Landbridge Group, without much Federal supervision.[5] Whether this commercial arrangement in Darwin impacts the MLSA implementation, remains to be seen. How the Chinese react to an Indian naval presence in Darwin and pull economic levers to pressure Australia will also be watched.

India holds some leverage in terms of the expansion of the Malabar Exercise (presently a tri-lateral exercise between the US, Japan and India) which Australia desires to join. New Delhi may utilize this leverage to seek reciprocal naval exercises around the Northern Territory to have optimal gains for its own navy. These may initially only include operations of P8Is from the Royal Australian Air Force base at Darwin or Cocos Islands. The specific modalities of bilateral exercises will have to be worked out between the two navies.

Sustained deployments by India in that part of the Indian Ocean will help develop a more comprehensive maritime domain awareness, which can be shared with all partner stakeholders such as littoral Indian Ocean Region states, Australia, U.S., and others.

The final goal of interoperability between maritime forces is to be able to work seamlessly with each other and from each other’s bases, when required. The benefit of such a pre-existing inter-operability was evident in 2018, when Indian yachtsman Commander Abhilash Tomy had an accident during a solo-around-the-world-race. An Indian surveillance aircraft (P8I) operating from an airfield in Mauritius,[6] located his stricken yacht, more than 4,000 kilometers from the nearest coast in the Southern Indian Ocean, and facilitated a rescue.

This MLSA with Australia assumes a much greater significance in the backdrop of the on-going India-China standoff in Ladakh. With several such logistics agreements in place and more to come, India is sending a signal to China: that on the grand strategic scale, China’s continuous, low-intensity pressure on the border areas is pushing India towards changing its current maritime posture. Going forward, India will keep its options open to make longer, sustained, forays into the South China Sea, as a part of bilateral or multi-lateral arrangements, and the Indian Navy will be capable, ready and supported for these deployments.

Commander Digvijay Sodha has 20 years of experience in the Navy. He has a MA in Defence Studies, Kings College, London and a MSc in Nautical Sciences and Tactical Operations, Cochin University of Science and Technology.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2020 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References

[1] Ministry of External Affairs, ‘India-Australia Joint Statement during the State visit of Prime Minister of Australia to India’, Government of India, 10 April 2017,

[2] Ministry of External Affairs, ‘Joint Declaration on a Shared Vision for Maritime Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific Between the Republic of India and the Government of Australia’, Government of India, 4 June 2020,

[3] ’21st Century Maritime Security for the Indian Navy’, Boeing,

[4] Khurana, Gurpreet S., ‘Indo-US Logistics Agreement LEMOA: An Assessment’, National MAritime Foundation, 8 September 2016,

https://maritimeindia.org/View%20Profile/636089093519640938.pdf

[5] Walsh, Christopher, ‘How and why did the Northern Territory lease the Darwin Port to China, and at what risk?’, ABC News, 12 March 2019,

[6] Goswami, Dev, ‘Updates: How Navy Commander Abhilash Tomy was rescued’, India Today, 24 September 2018,