Africa has been home to several Indian communities that were pivotal to the economic prosperity of regions that were formerly colonies. Even after these African nations got independence, Indian immigrant communities chose to stay on in their adopted homeland. They were forced to relocate to London between the 1960s and late 1980s when civil strife in Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania and Rwanda intervened. Many big East African Indian businesses have returned to these countries since the 1990s, reviving the rich legacy of economic and cultural ties that East Africa shares with the west coast of India, and Mumbai, in particular.

The Gujarati-speaking Jain community was the earliest to establish itself in the Portuguese colonies of East Africa, namely the ports of Mombasa and Kilwa, and Mozambique. They were successful because they adapted to different milieus and mores, even endowing mosques in the medieval port cities of Gujarat, like Cambay and Bhadreshwar, for their fellow Arab and African traders.[1] [2]

Kutchi-speaking Hindu Bhatias and Muslim communities (such as, the Memons, Bohris and Khojas[3]) from Sindh, Kutch, and Saurashtra followed. Zanzibar, and Pemba, an archipelago of islands north of Zanzibar, held promise after Sultan Sayyid Said decided to shift his capital there from Oman between the years 1832-40. Many Indian traders were co-opted into his mission to have unrivalled control over the slave trade.[4] Zanzibar and the Portuguese colony of Mozambique were both major slave marts in East Africa during the 18th and most part of the 19th centuries. Swahili-speaking merchants ventured into the interiors of the mainland in search of slaves, who formed the bulk of the labour supplied to plantation economies, such as the French Mauritius and Reunion Islands. They were also used to transport ivory to the coast as beasts of burden were vulnerable to attack by the deadly tsetse fly.

Slaves and ivory apart, the Indian traders were engaged also in a lucrative export trade in gold while their imports included Indian cotton cloth, spices, food grains, Chinese porcelain and silk. The arc of coastal trade (also called the dhow trade) stretched from the East African coast and further east to Aden, Muscat, and Hormuz, before reaching the west coast of India, and by the late 18th century, Bombay.

The transition to plantations

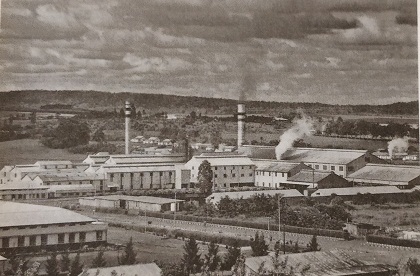

When the slave trade ended in 1873[5] the decline of Zanzibar, Pemba and the Mrima Coast, with its Indian communities, had already set in. To stop the slide in their fortunes, Indian traders began investing in clove plantations in these islands. A few families, like the Karimjee Jivanjees and Seth Allidina Visram’s, shifted operations westward to the mainland, where opportunity beckoned in the form of the first big-ticket infrastructure project, undertaken by the British government in East Africa: the ambitious, 582-mile Uganda railway line from Mombasa (Kenya) to Kisumu (Port Florence, Uganda) on Lake Victoria, which called for massive human resources.[6]

The British conceived of this railway line as “a Wedge of India driven into the heart of Africa”. According to Thomas R. Metcalf, in his book, Imperial Connections: India In The Indian Ocean Arena (1860-1920), they sourced coolies, surveyors and clerks; tracks, sleepers and coaches; training manuals; and later, staff to man the line, from Bombay, and Karachi, which was part of Bombay Presidency. The city’s Great Indian Peninsula Railways (GIPR) and Bombay, Baroda & Central India Railways (BB&CI) were there to replicate.

The terrain was treacherous, the deadline tight (1898-1905) and the conditions under which Indian labour had to work sub-human, leading to loss of life and livelihood. Of the 31,983 workers, 6,454 were declared unfit to work and 2,493 died due to their exertions. Such was the ruthlessness of Imperial policy.

The dukkawalas (Indian shopkeepers)

The construction of this railway line also attracted new merchant communities to the region. Among the few who successfully transitioned from Zanzibar to the British Protectorates (of Kenya and Uganda) was the ‘Ivory King’ and Ismaili Khoja trader, Seth Allidina Visram, once the biggest dukkawala, or shopkeeper (from the Hindi word, dukaan). The way in which he scripted his own fortunes shows how entire Indian communities came up around the shops that Indian traders set up. Writes Manubhai Madhvani in his autobiography, Tide of Fortune: A Family Tale, “As each section of track was completed, he (Visram) followed with commercial premises. He opened a shop at every large station along the 580-mile railway, provided food, clothes and all necessities for the workers on the railways; set up a branch of his trading empire in Kampala in 1898, and then opened stores in Jinja, up along the Nile in southern Sudan, and also in Kenya and Congo.” (Belgian Congo became Rwanda.) Provisions and clothing items were sourced from Bombay mostly.

Visram mentored young men from the Khoja community and from the newer migrant communities, like the Lohanas[7], who dominate the business world of Uganda even today. These large merchant families, who diversified into tea, coffee and sugarcane plantations, succeeded because of the business and family connections they retained with Bombay and community connections in present-day Gujarat, which is still a source of their staff. They formed the backbone of the economies of Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania (includes Zanzibar) after their independence in the 1960s and fought alongside native Africans in the nationalist and labour movements of these countries, having been a colonised people themselves.[8]

Civil war followed closely on the heels of independence in East Africa, the worst part of it being the brutal regime of General Idi Amin in the 1970s, which consisted of a mix of internecine tribal warfare (300,000 Ugandans died) and the acquisition of properties and businesses of affluent East African Indians.[9] Most Indians fled to the UK, United States and Canada.

Political and economic stability returned to this region in the 1990s. African leaders wooed back the big Indian plantation owners and industrialists with the offer of restitution of their businesses. This began a virtuous cycle of skilled Indian workers from the subcontinent moving to East Africa – just as they had done in the past.

Prime Minister Modi’s visit to Rwanda and Uganda may well result in a deeper engagement: a shared history at many levels offers lessons.

Sifra Lentin is Bombay History Fellow at Gateway House.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in or 022 22023371.

© Copyright 2018 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References

[1] Vastupal (1169-1240), a wealthy Jain merchant and administrator of the port of Cambay (known in the medieval period as Stambhatirth) ordered the construction of a Mosque for Arab settlers in this port. His contemporary, Jagdu (1193-1266), a Shrimali Jain, built a mosque at Bhadreshwar.

[2] Before the rise of Surat, the great Mughal port in the late 16th century, Jain merchants were concentrated in Porbandar, Jamnagar, Diu and Cambay from where they exported cotton piece goods (cloth), indigo, wheat, rice and even leather goods, to Hormuz, Mocha, Jiddah (Jeddah), Muscat, Aden, Zanzibar and Kilwa. In fact, the Kiswahili terms Bafta and Kaniki, which are still in use, have their origins in local Gujarati names for particular types of cloth.

[3] The Khojas are a Shia community which witnessed a split in the 1860s that occurred after the Aga Khan Case (1866) in the High Court of Bombay. Although there are many sects within this community, the two largest and most well-known in East Africa (and for that matter across Africa) are the Ismailis (followers of the Aga Khan) and the Ithna Asheris. Also see https://www.gatewayhouse.in/bombay-home-to-aga-khans/

[4] The Omani Sultans dominions roughly encompassed the Mrima Coast (it extends from Tanga on the mainland opposite the Pemba archipelago, to the Rufiji River), Pemba archipelago, Zanzibar island, Kilwa, and Mombasa from the 18th to late 19th century. Later the Mrima Coast, Kilwa and Mombasa were handed over to the British or IBEAC through Treaty.

[5] The first anti-slavery treaty between Britain and Oman was signed as early as 1803 but most were simply on paper as the trade went on unabated till the Anti-Slavery Treaty o9f 1873. [5] It was sustained pressure exerted by a series of anti-slavery treaties combined with British naval anti-slavery patrols, which culminated in a final Treaty signed between Zanzibar’s Sultan Seyyid Barghash bin Sa’id and Sir Bartle Frere, a former governor of Bombay, in 1873, that finally ended slavery in Zanzibar.

[6] It was to German Tanganyika and northwards to the British East Africa Protectorate (Kenya) and Protectorate of Uganda that the few of the old merchant families from Zanzibar shifted too. The British East Africa Protectorate (Kenya) was formed when the British Crown took charge of Sir William MacKinnon’s ambitious Imperial British East Africa Company (IBEAC) in 1895, while Uganda became a Protectorate in 1896. Sir William MacKinnon was one of the founders of the shipping agency MacKinnon MacKenzie and its British India Steam Navigation Company. Both companies were headquartered in Calcutta but had a strong presence in Bombay.

[7] Many other Gujarati speaking trading communities too immigrated to East Africa at the turn of the 20th century, like the Patidars (Patels), Parsis, Halar Oswal Jains.

[8] The Mombasa Indian Association, founded by L.M. Savle, was the precursor of the East African Indian National Congress (established 1914) in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda, which took its cues from the Subcontinent’s Indian National Congress. In 1924, the Kikuyu Central Association, headed by Manilal Ambalal Desai, encouraged Indigenous Africans to join forces with the Indians in their quest for equality. This Association had branches in all three East African nations.

[9] Madhvani, Manubhai with Giles Foden, Tide of Fortune: A Family Tale (Noida, Random House, 2009), pp. 134-37. Also, Kotecha, Bhanubahen, a translation by Leynore Reynell, On The Threshold of East Africa (privately published the Jyotiben Madhvani Foundation), pp 224-37.