The Indian strategic community is populated with China-watchers, experts on Pakistan and terrorism, naval and nuclear strategists. They scrutinise every little statement of Imran Khan’s or Xi Jinping’s and its larger impact on India. Arms purchase and defence procurement policy form the bedrock of strategic discourse in India. Paradoxically, America, the lone-pole in the current international order and India’s foremost strategic ally, does not spark much interest among Indian strategic affairs experts. There are numerous scholars commenting on India-U.S. agreements, but there is no one minutely looking at what America is up to and why. The Indian discourse on America is limited to U.S. arms sales to Pakistan or their president’s personality traits. There is hardly any discussion on what is happening inside America and its consequences for India’s bilateral and multilateral engagements.

The lack of rigorous scrutiny of America and its strategic plans defines our understanding of the limits and constraints on our autonomy that the global hegemon imposes. Since the 1950s, America’s strategy vis-a-vis China and Russia has had a direct bearing not only on our economy, but also on the character of our foreign policy. However, the Indian strategic community and even universities have preferred to look at India’s relations with China, Pakistan and Russia purely in bilateral terms, almost ignoring the direct impact of American grand strategy in determining our external policy choices. Take, for example, the Indian discourse on the 1962 war, which remains mired in Sino-India bilateral antagonism and devoid of the post-Stalin developments in Cold War politics.

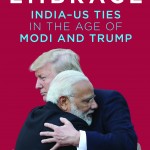

It is in this context that Varghese K. George’s book, Open Embrace: India-U.S. Ties in the Age of Modi and Trump, (Penguin, 2018), is a welcome addition to our foreign policy literature. George, a well-decorated journalist, presents a ringside view of the changing contours of internal politics in America since the arrival of President Trump in 2016 and its impact on the country’s external engagements. His narrative exposes the major blunders committed by the American liberal elite since the 1990s which catapulted President Donald Trump onto the centre-stage of American politics with his ‘America First’ rhetoric.

George has deftly used his stint as the correspondent of the Hindu in Washington to gauge the changing mood in America and the triumph of Trump from the people’s perspective. He has examined Trump’s systematic destruction of the post-war liberal order that was assiduously erected to advance the American century.

The author states, “Trump is dismantling Obama’s foreign policy legacy.” One will disagree here because Trump has continued with Obama’s ‘pivot to Asia’ and added more naval machismo to it by increasing the ‘freedom of navigation’ patrols in the South China Sea. He is further strengthening the alliances in the Indo-Pacific region, the foundations of which were laid even before Obama became president. The major deviation from Obama’s foreign policy legacy is the change in tone and tenor while dealing with China. Obama was circumspect; Trump has adopted a confrontationist approach against China. Trump’s position on war is much in conformity with almost all the post-war U.S. presidents. The only difference is that he believes that the U.S. should not spend all the money, fighting wars; its allies and partners should contribute more towards policing and war efforts in conflict zones that it decides upon. The alleged Russian involvement in American democracy may have divided the Democrats and Trump’s supporters, but when it comes to China there is a bipartisan consensus that the Chinese long march to replace the U.S. as the superpower cannot be postponed any further. And it is this need which makes India important to America.

The title of the book, Open Embrace: India-U.S. Ties in the Age of Modi and Trump, is interesting because it breaks away from the orthodoxy that often describes India-America ties in terms of discord or estrangement. George refers to Prime Minster Modi’s address to the U.S. Congress in June 2016 where he said that the Indo-U.S. “relationship has overcome the hesitations of history”. He does not elaborate, though, on the historical constraints hidden in that phrase.

Modi was probably referring to ‘the hesitations’ imposed by the Indian historical and strategic need to feign distance from America. Nehru, whose projects for modern India were inspired more by President Franklin. D. Roosevelt’s New Deal policy than any ideological tilt towards the Soviet Union, could not afford to openly embrace America because his nationalism was rooted in opposition to the West. Nehru was aware that open embrace of America, the leader of the western world, would make his nationalism look less robust. America too did not want Nehru to look like a lackey of the West because the U.S. foreign policy establishment wanted him to stand as tall as Mao Zedong. For America, Nehru was the poster boy of western democracy in the Afro-Asian world that China was trying to woo with its brand of Communism. Nehru was also the U.S.’ best bet to prevent Communism from making inroads into India.

Nehru’s proclamation of Non-Alignment also precluded him from open display of admiration for American progressives, his ideological mentors since the 1930s. Nehru, a part of the western elite network, enjoyed the agency to gather the non-Communist neutral nations to launch the Non-Alignment Movement in 1961. This happened during Kennedy’s presidency, at a time when Indo-U.S. ties had entered a golden phase, with India taking a strident stand against China and giving full support to U.S. efforts in bringing the Tibetan issue to the centre-stage of international discourse.

Modi has jettisoned the old mask of “strategic autonomy”, used by Nehru in his dealings with America, for two reasons. Firstly, his nationalism is moored to Hinduism. Secondly, unlike Nehru, who cloaked his elitism under the banner of socialism, Modi doesn’t hide his affinity with the international, populist, right-wing, authoritarian ideology that proclaims to be anti-elitist in character. The current global conservative agenda, which hinges on anti-immigration, Islamophobia, anti-liberals and love for war and capitalism, is one that Modi has identified with since his formative years in the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). This ideological bonding makes Modi and Trump natural bedfellows and has been a major factor in the upswing in Indo-U.S. ties over the past five years.

George has brilliantly brought out that Modi’s world view is shaped by Hindutva strategic doctrine whose main concern is to shed the imagery of non-violence attached to Hinduism and somehow make it look more aggressive and militaristic. In sharp contrast to Nehru, branded as an idealist, Modi is being sold as a pragmatist. However, what needs to be emphasised is that just as Nehru’s image as a liberal democrat was useful for America in the 1950s, Modi’s macho image suits current American strategic needs in the Indo-Pacific. Just as Nehru was granted agency to pursue his independent foreign policy Modi too will be allowed a certain degree of independence. However, just as Nehru was eventually made to tow the U.S. line against China in the late 1950s, Modi too will be expected to move in accordance with the needs of the U.S. empire. Nehru’s Non-Alignment Mask and Modi’s Hindutva Mask only help to hide the deep-rooted elite networks that guide Indo-U.S. engagements. To understand the nuances of these networks, our scholarship needs to deconstruct the way the U.S. empire works and exercises control over global affairs.

George has given us a thought-provoking book that offers an accurate account from deep inside the metropole. He has narrated the course of evolving Indo-U.S. ties under the two conservative leaders, both engaged in mixing nationalism, religion and populism to save and advance the global capitalist order. His well-structured and nicely organised book is written in simple language; he does not resort to jargon. This book should be read by scholars of India-America relations and Indian foreign policy experts.

Open Embrace: India-U.S. Ties in the Age of Modi and Trump by Varghese K. George (Penguin, 2018)

Atul Bhardwaj is an Honorary Research Fellow at the Department of International Politics, City, University of London. He is a former Indian naval officer, who, in a 17-year-long career, has served on many Indian navy warships and establishments.

This review was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2019 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.