This is the second in a series about the ASEAN nations.

Cambodia is a member state of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) with the fourth smallest population and the second lowest GDP.[1] It has been trying to transform itself with help from the West – and its ideals of a liberal democracy – for the last 25 years. Such transformation is elusive. China is now in the principal benefactor’s seat. Second, Cambodia may have acquired all the makings of a democratic framework, but democracy in spirit and substance does not exist.

Elections are meant to showcase a country’s democratic credentials, but the elections to the National Assembly in July 2018 drew international attention for all the contrary reasons. Phil Robertson, deputy director for Asia at Human Rights Watch, observed, “What occurred (on 29 July) was a mockery of democracy, not a promotion of it.”[2]

The build-up to polling day was fraught with ominous developments. The president of the main opposing party, Cambodia National Rescue Party, was replaced amidst an increasing crackdown on the media, political dissidents and civil society groups. His successor, Kem Sokha, was arrested and charged for treason, and the party was dissolved. This left the ruling party – Cambodia People’s Party – in an unchallenged position. No wonder it won all 125 seats in the assembly, while all the other parties drew a blank. The results thus showed Cambodia’s emergence as a de facto one-party state.[3]

Prime Minister Hun Sen, who has been in power for the past 33 years – one of the longest serving leaders in the world – provided stability since 1997 to a nation that was devastated by the Khmer Rouge under Pol Pot (1975-79). That was when at least 2 million people, a quarter of the country’s total population, died.[4] This dark era was followed by the Vietnamese occupation from 1979 to 1992.[5] Through these and other changes, Hun Sen was a vital factor of political continuity – but a democratic outlook is not his strong suit, as the July elections showed.

Faux democracy has another troubling aspect. The Cambodian people, like other peoples of the Indo-China region, seem to accord priority to poverty alleviation and employment over democracy and liberty. The government thus monitors political activities closely and concentrates on seeking resources from abroad, especially China, to accelerate the pace of development.

Alignment with China

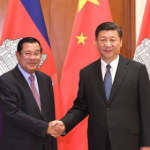

Among all the ASEAN countries, Cambodia and Lao PDR are widely considered to be China’s closest allies. Experts on the region have said that 2018 is an important milestone as it marks the 60th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between Cambodia and China. Bound together by a “Comprehensive Strategic Partnership of Cooperation”, leaders of the two nations noted, during the visit to Cambodia of Chinese Premier Li Kequiang in January 2018, that their relations experienced “profound development, bringing substantial benefit to the two peoples.”[6]

The Belt and Road Initiative has elicited Cambodia’s full support as also the South China Sea issue.[7]

The two governments have been working in concert to enhance strategic communication through close high-level contacts, expand defence and economic cooperation, and strengthen coordination within the framework of the Mekong-Lancang Cooperation.

Cambodia’s dependence on China, which is emerging as the most important economic partner, may be gauged from the following[8]:

- Between 2013 and 2017, China was the largest foreign direct investment partner, with its investments totalling $5.3 billion.

- Cambodia received $4.7 billion from China in the form of grants and soft loans. Of Cambodia’s external debt amounting to $9.6 billion, 42% is owed to China.

- Bilateral trade stood at $5.5 billion in 2017, which was an increase of 22% over the previous year. The two governments are committed to take it to $6 billion by 2020.

The Koh Kong project has drawn widespread attention: a Chinese company has been granted a 99-year lease to 20% of Cambodia’s coastline at a modest price. It is a $3.8 billion project comprising a port, an airport and a colony for Chinese nationals exclusively. It has “very familiar echoes of other projects in the region and around the world,” wrote Bates Gill, a professor at Macquarie University.

Other partners, India included

Where then do other partners stand? The role of western nations in Cambodia seems to be on the decrease, frustrated as they are with the nation’s growing slide towards authoritarianism. Where the United States and European Union once provided financial aid of a material nature to rebuild Cambodia into a liberal democracy, the EU is now poised to impose trade sanctions in response to these internal political developments.

Japan and South Korea continue to be in the play, providing substantial economic assistance and business linkages in an attempt to balance Chinese dominance.

Among all the CLMV countries,[9] Cambodia probably received the deepest imprint of Hindu and Buddhist influences emanating from India. The Angkor Vat Temple symbolises the India connection. When the temple needed restoration, India was the most appropriate partner to whom to turn. The project, managed by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), proved a success. It attracts over 2.2 million tourists a year, giving rich dividends to the nation; it also led to the restoration of other temples.

Beside culture, archaeology and tourism, India has made special efforts toward human resource development, a large and growing need in Cambodia. It has offered training under the Indian Technical and Economic (ITEC) programme[10] and granted scholarships at Indian universities. Such bilateral cooperation has also included Quick Impact Projects (QIP) under the Mekong Ganga Cooperation (MGC) Initiative in agriculture, health, women’s empowerment and sanitation, which have received an “overwhelming response” and created “a distinct and visible impact.”[11] India also offers some concessional credits and grants. Bilateral trade, though, is modest at $168 million in 2017.

While in India to participate in the ASEAN-India Commemorative Summit in January 2018, Prime Minister Hun Sen paid a state visit and held bilateral discussions with the Indian leadership. The two governments reaffirmed their “common goal to further strengthen the bilateral relations as well as cooperation in regional and international organisations.”[12] External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj undertook a follow-up visit to Cambodia to co-chair the joint commission meeting in August 2018. It resulted in the conclusion of two new agreements.[13]

Historians claim that in the past, before colonialism took hold, India had scored over China in battles for cultural influence in Cambodia. But looking at the relationship now in all its totality, China is racing miles ahead of India.

Rajiv Bhatia is Distinguished Fellow, Gateway House and a former ambassador to Myanmar.

This is the second in a series about the ASEAN nations.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2018 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References

[1] Cambodia’s population is 15.6 million, the fourth smallest in ASEAN after Brunei, Lao PDR and Singapore. Its per capita income in nominal terms was $1498 in April 2018, the second lowest in ASEAN – after Myanmar.

[2] Ellis-Petersen, Hannah, The Guardian, Cambodia: Hun Sen re-elected in landslide victory after brutal crackdown, 29 July 2018, <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jul/29/cambodia-hun-sen-re-elected-in-landslide-victory-after-brutal-crackdown>

[3] ‘“This is the end of the road for democracy in Cambodia, though I’ve thought the country has been authoritarian for years,” said an expert.’

Massola, James, and Nara Lon, The Sydney Morning Herald, Cambodia election ‘the end of the road for democracy’, 30 July 2018, <https://www.smh.com.au/world/asia/cambodia-election-the-end-of-the-road-for-democracy-20180729-p4zubq.html>

[4] The horrors of the devilish regime were well portrayed in the 1984 Oscar-nominated film, The Killing Fields, directed by Roland Joffe.

[5] Monarchy was restored in 1993 when Norodom Sihanouk returned after a long exile in China and North Korea. His son, Norodom Shimoni, became the king upon Sihanouk’s abdication in 2004.

[6] Office of the Council of Ministers, Kingdom of Cambodia, Joint Communique between the Kingdom of Cambodia and the People’s Republic of China, 11 January 2018, <http://pressocm.gov.kh/en/archives/21867>

[7] On 13 July 2012, Cambodia single-handedly blocked the issuance of a joint statement by the ASEAN foreign ministers for being critical of China on this matter. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-18825148

[8] Cabinet of the Prime Minister of Cambodia, Cambodia New Vision, Remarks at the 60th Anniversary of Cambodia-China Diplomatic Relations Establishment, 2 July 2018, <http://cnv.org.kh/remarks-60th-anniversary-cambodia-china-diplomatic-relations/>

[9] Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar and Vietnam.

[10] 1,400 Cambodian nationals were trained during 1981-2917.

[11] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, India-Cambodia Relations, November 2017, <http://www.mea.gov.in/Portal/ForeignRelation/1_Cambodia_November_2017.pdf>

[12] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, India-Cambodia Joint Statement during State Visit of Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Cambodia to India (January 27, 2018), 27 January 2018, <https://www.mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/29394/IndiaCambodia_Joint_Statement_during_State_Visit_of_Prime_Minister_of_the_Kingdom_of_Cambodia_to_India_January_27_2018>

[13] They are:

MOU on cooperation between Foreign Service Institute of India (FSI) and the National institute of Diplomacy and International Relations of Cambodia (NIDIR); and MOU for Conservation/Restoration of Preah Vihear temple, Cambodia.