The sweep of protests around the world found its way to Pakistan last week. Pakistan’s protests are both alike and dissimilar to the ongoing, widespread demonstrations. Similar are the issues of corruption, inflation and rising taxes; specific and endemic to Pakistan since the restoration of democracy in 2008, are manipulated elections and flawed law enforcement.

Unlike uprisings elsewhere, the Pakistan protests are not spontaneous. They are a deliberate, contrived move, encouraged and coordinated by a mix of actors and conspiracies that has defined the Pakistani polity.

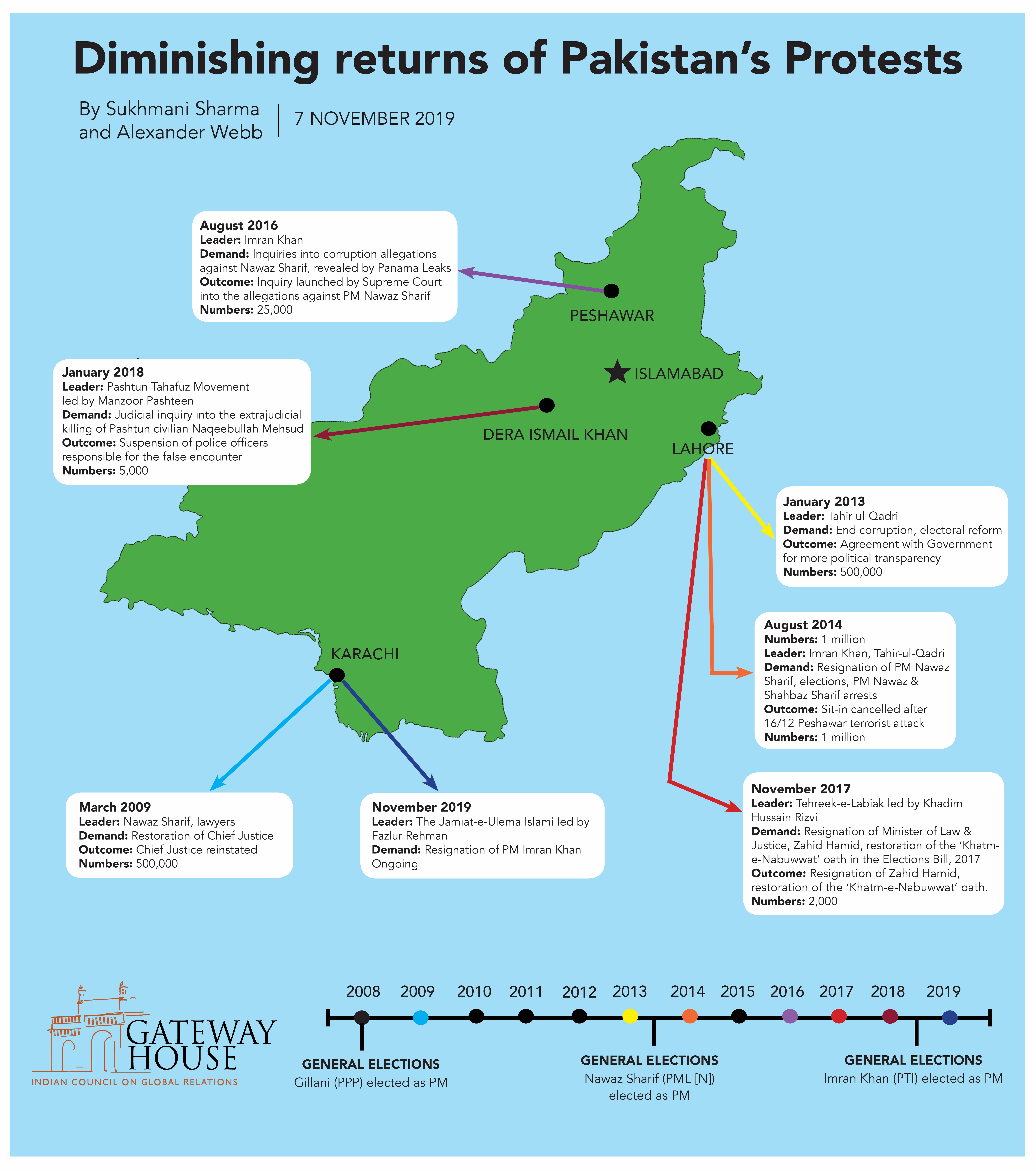

The ongoing demonstration in Pakistan follows a pattern of similar events – seven, so far – that have taken place in the last 12 years in that country. Each time, the same method is employed: a Long March to the capital, Islamabad. Marches in the past have been largely peaceful and have been powerful signs of popular unrest, supported by large numbers of participants – upto 1 million – from all classes and across all Pakistani states. But last week’s march from Karachi to Islamabad was different: its increasingly narrow support base and the lack of endorsement by the Army.

The latest Azadi March has been initiated by career politician and cleric, Fazlur Rehman, who leads the Jamiat-e-Ulema Islami (JUI), an Islamist political party with a strong base in the Pashtun-dominated Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. His stated goal is to hold Prime Minister Imran Khan accountable for the economic difficulties that Pakistanis are facing following the austerity measures that have ensued from the Khan-negotiated IMF $6 billion bailout earlier this year. Rehman, a former member of the National Assembly, lost his seat in one of the Dera Ismail Khan constituencies in the 2018 general election. Since then, he has been calling Khan’s election illegitimate and through this march, has been demanding his resignation.

Rehman’s resistance bears a strong resemblance to previous marches: the 2013 and 2014 demonstrations by Pakistani-Canadian Islamic scholar Muhammad Tahir-ul-Qadri; and the 2017 march from Lahore to the capital, organised by an obscure right-wing party, Tehreek-e-Labbaik (TLP), led by Islamic scholar, Khadim Hussain Rizvi. The latter did have success: it demanded and obtained the resignation of the Law and Justice minister, Zahid Hamid, who had presented a controversial amended Elections Bill, challenging the oath that candidates had to utter in declaration of their total faith in the Prophet.

The current movement led by Rehman is unlikely to achieve its desired result. The 2014 march and sit-in against Nawaz Sharif’s government, was a joint effort between Tahir-ul-Qadri and then opposition leader, Imran Khan. Khan’s gradual rise to power since 2011 has been greatly aided by the military, which played a key role in his efforts to topple Nawaz Sharif in 2014 – unlike now. Khan can certainly continue to rely on the Army’s backing, made clear by its statement of support last week for ‘democratically elected governments’. Khan’s recent decision to extend the term of the Chief of Army Staff, General Bajwa, has ensured the Army’s continuing support.

Rehman’s march has also excluded a large section of Pakistanis – the women – which has earned him heavy criticism despite this being consonant with his extreme religious views. These views may have fuelled this loud and intense protest, but this one lacks the credibility of Khan’s 2014 and 2016 more mainstream and successful marches. Additionally, the two major opposition parties, the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) and the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML(N)), which were initially supportive, have been distancing themselves from Rehman’s march.

This march is, therefore, not strong enough to bring about the desired change: the resignation of the Prime Minister. It does, however, come at a time when Imran Khan’s position has already been fragilised by a floundering economy and the grey-listing of Pakistan by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). His management of this crisis will be decisive for his political survival.

Sukhmani Sharma is Website Associate at Gateway House.

Alexander Webb is an Intern at Gateway House.

Designed by Daniella Singh.

This infographic was exclusively created for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2019 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.