The COVID-19 catastrophe has triggered a change in many areas and geopolitics is no exception. Whether the changes are new or just an accentuation of previous trends may be debatable, but there is little doubt that the old ways of thinking and old policies need to change, and adapt themselves to new power realities and dynamics. This applies in particular to the Indo-Pacific, which is currently the most active region in the global political landscape.

China’s assertiveness has given way to plain aggressiveness, in speech and action, as witnessed on a whole spectrum of issues: Beijing’s resistance to international calls for investigation into the origin and outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic and China’s culpability in it; aggressive maneuvers in the South China Sea; Hong Kong; Taiwan; trade and technology disputes with the U.S.; serious tensions with Australia; and the still unresolved India-China border standoff, which has resulted in a violent conflict. These issues have been handled with a mix of defensiveness and indecisiveness by the U.S. and other powers. The overall perception thus created is that, while China is losing international goodwill and eroding its public image, it has been gaining in strength, while its adversaries remain in disarray. The implication of China’s victory at the WHO, where the diplomatic campaign for enquiry into the origin of the pandemic fizzled out, in favour of a general evaluation of the global response, has not been lost on the Indo-Pacific region.

Nations from India to the Philippines, and from Australia to Kenya and South Africa are all interested in the U.S.’s position now regarding the Indo-Pacific. They notice that the U.S. has recorded the largest number of confirmed COVID-19 cases and fatalities in the world; it is caught up with pressing internal preoccupations; and its Indo-Pacific strategy is losing its edge. Washington’s latest move – the proposal to transform G7 into G10 or G11, is also indicative of the U.S.’s intention to garner assistance from other countries in the region. All the countries suggested for inclusion – Russia, India, Australia and South Korea – are from the Indo-Pacific. Indonesia deserves to be added to this list.

As a new geopolitical construct, the Indo-Pacific has inspired endless debate and reflection in recent years. The region’s evolution in the COVID-19 era, however, demands that attention be paid to what nations should do to secure their interests and to promote the region’s stability, security and prosperity. So far, the term ‘inclusivity’ has been used as a mantra by most countries, to convey that China should be included in all deliberations and arrangements related to the region. But the difficulty is that China is unwilling to follow international law and norms of diplomacy and is actively engaging in an aggressive manner instead. Recognising this, some scholars have gone to the extent of suggesting the formation of an anti-China ‘Indo-Pacific Treaty Organisation’, à la NATO.[1]

Military alliances are perhaps not needed. There are other, more calibrated ways of ensuring geopolitical balance in the region. These measures should be based on the assumption that in the foreseeable future, the region will face a form of cold war or a sharpened strategic contestation, involving China on one hand and several other nations, on the other.

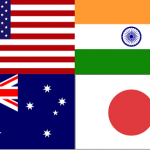

This is where the quadrilateral partnership or Quad, composed of the U.S., India, Japan and Australia, becomes essential. The view of strategic analysts that China’s unacceptable behavior will ensure that the Quad becomes an effective coalition is now proving true.[2] In recent months, the four-way partnership has become more active, and resilient, but further steps can be taken. Some specific measures are:-

a) The Quad needs to refine its approach towards ASEAN. None of ASEAN’s ten members are inclined to join the group but several may be open to forging ‘side relationships’. Indonesia, Vietnam and the Philippines may be interested in deepening their strategic cooperation, individually or collectively, with India, Japan and Australia. Plurilateral dialogues involving these six countries should begin now, or should be built up further where they already exist – such as the trilaterals comprising India, Australia and Indonesia, and India, Japan, and Indonesia. Senior officials from Vietnam, South Korea and New Zealand became the Quad’s weekly interlocutors through videoconference on COVID-19 related issues under the umbrella of ‘Indo-Pacific Dialogue’ during March-May 2020. The ambit of these discussions should be expanded.

b) To enhance its diplomatic and strategic gravitas, the Quad should work seriously on strengthening its pillar of economic and technological cooperation. Action and actual delivery rather than merely high-sounding announcements, would be the way to go.

c) The 24th edition of Malabar Naval exercises, due in July-August 2020, should have four participating Navies, not three. The desirable inclusion of Australia is an essential take-away from the successful Modi-Morrison virtual summit.

d) The Quad can no longer ignore the interest of several European powers – France, U.K. Germany and the E.U. itself – to contribute towards balancing power in the Indo-Pacific. They have assets such as political strength, diplomatic acumen, existing naval and maritime connections, and a reservoir of know-how, technology and capital, which can be leveraged.

e) Internally, the Quad should consider a few reforms in its functioning. Mid-level officials made a significant contribution through five meetings between November 2017 and November 2019, but the level of engagement needs to be elevated to at least one meeting at the foreign secretary and foreign minister[3] levels every year. The ministers should consider eschewing diplomatic coyness and start issuing joint statements post meetings.

The tensions building in the Indo-Pacific, due to the COVID-19 crisis and other underlying issues, send a clear message – neither appeasement nor bravado but fortitude and resilience are necessary. As the Indian government prepares to handle the current adversity on the northern border, it could consider postponing the impending Russia-India-China (RIC) meeting and instead convene a special Quad meeting to brief partner countries on recent developments.

Rajiv Bhatia, Distinguished Fellow, Gateway House, is a former ambassador to Myanmar, with extensive diplomatic experience in the region. He comments regularly on developments in the Indo-Pacific.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in

© Copyright 2020 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References

[1] Mansheetal Singh and Megha Gupta, ‘Covid-19: China’s Adventurism with Taiwan and the South China Sea’, 9Dashline, 28 May 2020. https://www.9dashline.com/article/covid-19-chinas-adventurism-with-taiwan-and-the-south-china-sea.

[2] Rajiv Bhatia, ‘A case for the Quad’s reappearance’, Gateway House, 2 January 2018. The author wrote: “Its trajectory will be shaped largely by China’s future actions.’ https://www.gatewayhouse.in/quads-reappearance/

[3] The Quad’s first foreign ministerial meeting took place in September 2019. Further, the four foreign ministers held a videoconference with the foreign ministers of Brazil, Israel and South Korea in May 2020. The rationale for the inclusion of two countries – Brazil and Israel – was left ambiguous, but the theme was Covid-related issues.