Abstract

Digital services innovation and the shift to online commercial transactions is contributing to more inclusive global trade and development. However, there are challenges associated with reaping these benefits, as there is scarce guidance on best practices in digital regulatory settings, and multilateral governance regimes around digital trade remain in their fledgling stages. International digital regulatory cooperation, including building resilience in global value chains (GVCs), is gaining priority. This Policy Brief considers the evidence base on digital economy policies which strengthen business resilience and are inclusive of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises’ (MSME) access to GVCs. It goes on to recommend G20 actions to boost mutual learnings on digital regulation. Widespread implementation of digital regulatory good practices will enable greater international regulatory interoperability, unleashing more inclusive growth opportunities in digital trade and paving the way for the development of the required multilateral governance.

The Challenge

Digital services innovation is a critical driver of industry transformation and global economic growth, development, and diversification. The beneficiaries are potentially widespread across and within economies, including the smallest and least developed economies, the weakest micro-enterprises, and the most remote consumers and producers. The trend for businesses and consumers everywhere to shift domestic and international commercial transactions online continues to intensify, with a strong potential for increased and more inclusive global employment and income opportunities.[1]

However, multilateral governance regimes around digital trade remain in their early stages, and best practice in digital regulatory settings remains uncertain. The outcome is an intensifying divergence of domestic digital regulatory settings within the G20, which negatively impacts international trade and investment. The average cumulative global increase in services trade restrictiveness was five times higher in 2022 than in 2021,[2] with barriers to cross-border data transfers topping the list. There has also been a marked increase in the heterogeneity of digital regulatory restrictions, which can in itself constitute a significant barrier to trade.[3]

The increasing level of restrictiveness and intensifying divergence in regulatory approaches to digital trade both have a negative impact on MSME access to inward investment opportunities and access to export market prospects via digital GVCs.

A recent Indian government report[4] notes that the challenges are truly global, and India is leading the way in attempting to resolve them at a national level through its digital public infrastructure initiatives. Despite the global rise in internet connectivity, cross-border digital commerce remains beyond the reach of many small companies and billions of consumers. The report suggests that, as India’s Open Network for Digital Commerce (ONDC) initiative grows, it could influence digital commerce on a global scale by promoting cross-border trade and accelerating and democratising digital commerce across markets. It recommends that, for ONDC to transform digital commerce beyond India’s borders, four key enablers should be in place to support international digital commerce, including seamless cross-border e-payment settlements and global cooperation.

Building trust in the global digital economy is one of the most important challenges of the twenty-first century. Collaboration towards regulatory streamlining, convergence, and interoperability, keeping in mind public policy priorities emphasised by individual nations, needs to be central to the G20 agenda. In repeatedly failing to address this challenge in a consistent and concrete manner, the G20 has been overlooking the best chance for global macroeconomic recovery. This year’s G20 summit offers India, a global digital giant with a vision of democratising digital commerce, with the opportunity to turn the tide. This is especially pertinent in 2023, with Asia’s intra-regional share in digital services exports now outpacing growth in other regions.[5]

The G20’s Role

The accumulating international evidence suggests that digital adoption has a big positive impact on MSME growth. Business surveys by the International Trade Centre (ITC) show[6] that digitally enabled financial services, information and communication technologies (ICT), transport and logistics, and business and professional services have become the connective tissue that links various parts of a supply chain and are now at the centre of contemporary economic trends. These ‘connected services’ are spearheading digital innovation and contributing to more growth in value-added industry output and employment in low-income countries compared to any other sector. Firms in all sectors are more competitive when they have access to high-quality connected services, which also make societies more equal, allowing small businesses to integrate into GVCs and adopt digital technologies to produce and engage with buyers, suppliers, and support institutions efficiently.

The ITC argues that services can turbo-charge inclusive economic transformation but they must be connected. This calls for a regulatory approach creating conditions for globally competitive connected services at home and reducing trade restrictions so that companies can access these services internationally. ITC calls for regulatory reforms that reduce compliance costs, encourage investment, and facilitate access to foreign providers for crucial connected services that may not be locally available, ensuring that local SMEs have access to the high-quality services that they need to participate in GVCs.

India is a major global player in the digital economy, with global leadership responsibilities to take up this issue as the 2023 G20 chair. A McKinsey report[7] recorded India as the world’s largest and fastest growing digital consumer market, next only to China in 2018; in 2023, broadband internet subscribers stand at over 800 million and telephone subscribers at over 1 billion.[8] The estimated productivity improvement unlocked by digitalisation could create 60–65 million jobs by 2025, most of which would require digital skills. Application of digital technologies to financial transactions places India at the top of the list of countries with the largest number of real-time digital payments transactions.[9] India reported more than 49 billion such transactions in 2021; China is a distant second with 19 billion.[10]

India is well placed to initiate a new collaborative G20 forum for the sharing of digital regulatory experiences. G20 members face similar challenges and can learn much from each other in dealing with gaps in regulatory settings and strategising to reduce divergences in regulatory approaches which impact trade, investment, and global economic growth. The G20 efforts comprise the bulk of the cooperative initiatives required, and these can establish frameworks that facilitate paths for broader multilateral collaboration.

One recent study[11] found that an increase in internet bandwidth led to an increase in the total volume of goods traded by India. This study recommended that policy and regulatory settings should focus on the development of the digital ecosystem of India as a whole rather than force data localisation, thus ensuring that businesses find it cost-effective and efficient to operate in India. Another recent study[12] found that digital services imports in production by Indian MSMEs[13] are positively correlated with gross value-added MSME output. Regression results suggest that these imports also have a significant positive effect on MSME productivity and employment. The study cites the criticality of cross-border digital transmissions, as reiterated by a variety of Indian business and think-tank stakeholders. Openness to cross-border digital flows and global regulatory cooperation in this area are widely considered to be essential to boost MSME growth as well as the economy in general.

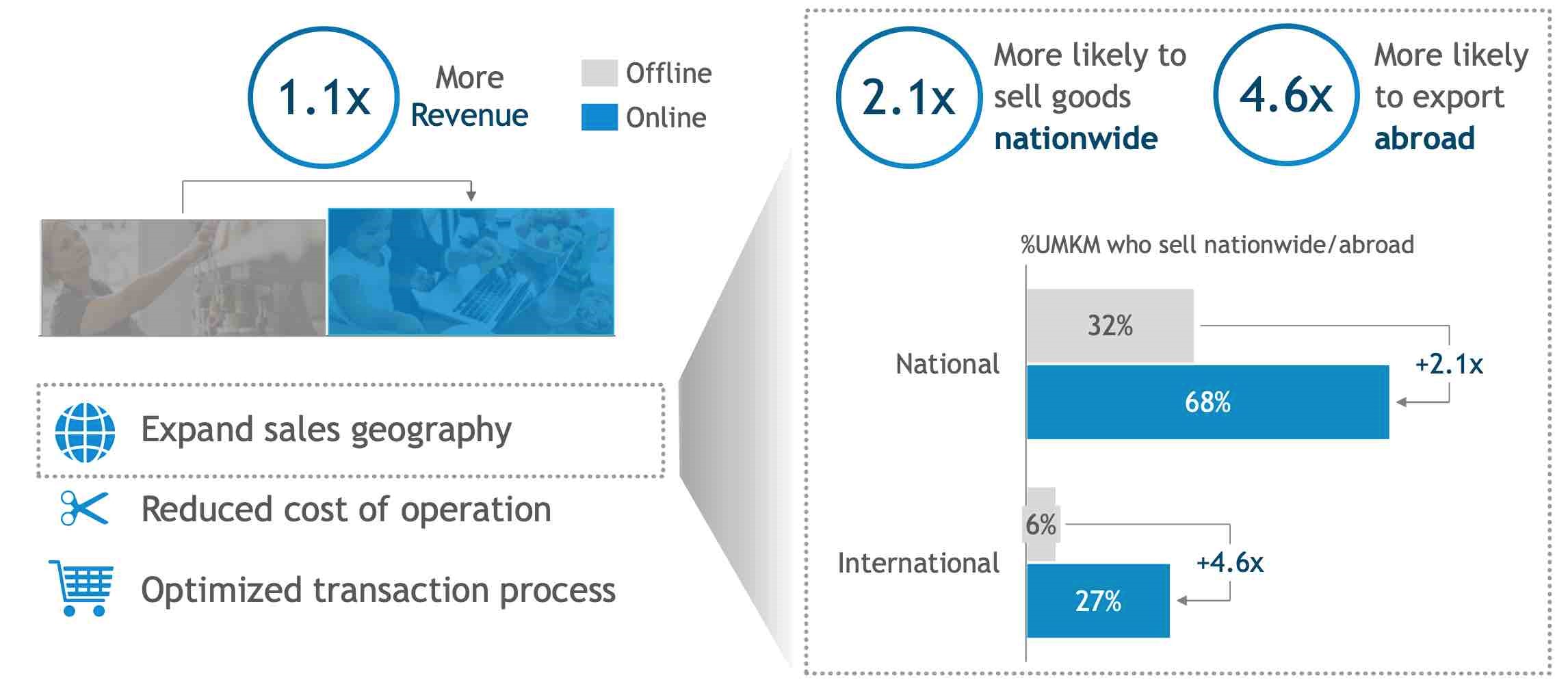

Indonesia, the 2022 G20 chair, has a similar interest in ensuring that policy and regulatory settings are conducive to MSME digitalisation and growth. MSMEs are the backbone of the Indonesian economy, and digital services play a fundamental role in supporting the growth of MSMEs. A string of Indonesian studies[14] have identified the adoption of digital services as vital to MSME survival and post-pandemic recovery across industry sectors. Forty-four percent of MSMEs surveyed went online during the pandemic and more than 40 percent now sell their products through online marketplaces. MSME surveys show continued acceleration in digital adoption; going digital is helping MSMEs earn income and optimise costs by expanding the consumer base both nationally and globally through international trade (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Impact of Digitalisation on MSMEs in Indonesia

Source: Indonesian Services Dialogue (2021)

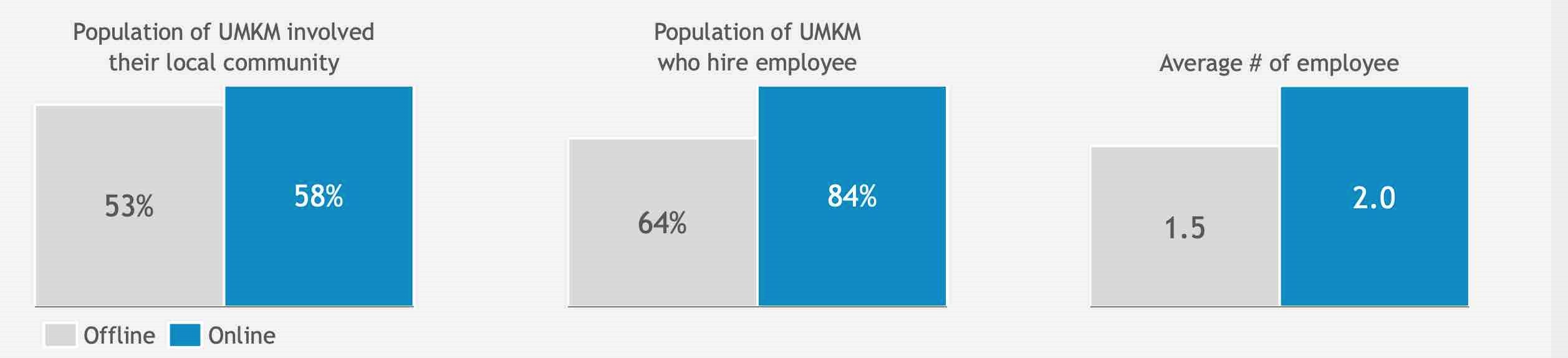

MSMEs using digital technology are also more likely to have higher participation in local communities and employ more local people (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Impact of Indonesian MSME Digitalisation on Local Communities

Source: Indonesian Services Dialogue (2021)

A recent study by the Indonesian Services Dialogue (ISD)[15] conducted surveys of 764 MSMEs, which showed that more than 98 percent use digital services and almost all use mobile phones. Digital adoption is the highest for core business processes such as software application services as well as for marketing tools such as online platforms, social media, and operating system and other supporting software. Around 60 percent of the surveyed MSMEs use digital services for business operations and delivery of goods or services, and 50 percent use digital services to purchase raw materials. Fewer use digital technologies for financial systems and human resource processes. However, as MSMEs grow, the need for digitalisation of these business functions tends to increase.

This widespread digital adoption has had a significant impact, with overall increases in the scale of business as measured by consumer base, revenue, profits, assets, workforce numbers, and the number of product variations sold. On average, the consumer base increased by 31 percent, employee numbers increased by three per business unit, product variations increased to four, and revenue and profits increased over 20 percent. Business revenue increased for 80 percent of the MSMEs surveyed, operational costs fell for 63 percent, and 85 percent expanded their businesses. The impact was especially notable in the transportation and communication sectors, where 88 percent of MSMEs experienced revenue gains and 100 percent expanded their business. 77 percent of the MSMEs in forestry, agriculture, and fisheries experienced cost reductions. The average monthly reduction in MSME logistics costs alone was 16 percent, translating to an estimated monthly cut of US$413 in average costs per business unit for small businesses and US$4,206 for medium-sized businesses. The ISD recommends that the regulatory environment should focus on ensuring that the digital ecosystem is conducive to MSME and start-up growth. Business stakeholders in Indonesia see a need to lower barriers of entry to acquire and access digital services and note that the imposition of customs duties on e-transmissions, even if set at 0 percent, increases administrative and compliance costs and potentially holds back digital adoption.[16]

The MSME business expansion brought about by digital adoption generates increases in tax revenues (corporate income taxes, consumption or value-added taxes, and personal income tax from increased revenues of workers employed by MSMEs). Some experts note that imposing tariffs on e-transmissions will likely lead to higher prices and reduced consumption, in turn slowing GDP growth and shrinking tax revenues.[17]

Recommendations to the G20

Focus on facilitating digital adoption by service MSMEs

The services sector is the SME sector, and SMEs form the backbone of most economies. For most developing and emerging economies, micro-enterprises are critical to bringing households into the formal workforce. In India, MSMEs are a key growth engine, accounting for 30 percent of the country’s GDP[18] and holding a share of almost 40 percent of India’s gross manufacturing value-added output. In 2020–21, MSMEs held a 50 percent share in Indian merchandise exports. Several studies have drawn attention to factors stifling the growth of MSMEs in India, including the costs of regulatory compliance, poor use of technology, and lack of international market linkages.[19]

It is urgent for the G20 to develop a more intensive focus on good regulatory practices for the services sector, especially digitally enabled and connected services, as well as on ubiquitous MSME presence in the sector. The G20 governments tend to focus on the regulatory challenges around global big tech and ignore the real and urgent policy and regulatory needs of local MSMEs. These days, services businesses, irrespective of their size, are born digital and potentially global, with the international market only a click away. Policy and regulatory settings for the digital economy need to enable rather than constrain MSMEs from both digitalisation and internationalisation. The potential for digital tools to reduce compliance burden and improve time and cost efficiency provides a new focus for improving regulatory efficiency.

Benchmark against international practices to implement good regulatory practices for the digital economy to encourage innovation and facilitate digital services trade and investment

Digital services innovation sits at the centre of the digital trade conversation. The technological landscape is rapidly evolving, and regulators are facing considerable challenges in keeping pace. A key feature of good regulatory practice is ensuring that regulatory reforms are not conducted in silos but in a consultative manner with an eye on the international dimensions and involving all relevant government agencies.

Sound measurement is crucial to informing and guiding policymakers in undertaking diagnostics, assessing the impact of reform options, monitoring progress, and evaluating the efficiency and efficacy of implemented policy actions. There are many international dimensions to consider in regulatory design, some of which are unintended consequences. In 2018, the G20 Toolkit for Measuring the Digital Economy[20] highlighted critical gaps in indicators for monitoring digital transformation. The G20 should pursue this work, encouraging the implementation of the toolkit and tracking achievements and persisting gaps.

Domestic regulatory coherence should be encouraged by implementing good practices, including anticipating problems, consulting stakeholders, and discussing solutions. Businesses need greater transparency of their regulatory obligations. The G20 should lead the development and utilisation of the capacity-building tools required for digital structural reform, such as regulatory handbooks and toolkits. A joint OECD/WTO study[21] showed, for example, that G20 countries could achieve savings of US$150 billion in services trade costs by implementing the principles in the WTO Reference Paper on Services Domestic Regulation.[22]

Strengthen international regulatory cooperation for cross-border digital connectivity by initiating a new G20 regulators forum

Although policy objectives differ, the G20 members face similar challenges, and there is much to learn from each other’s success stories, including identifying gaps in regulatory settings and strategising to close them. Greater international regulatory collaboration and cooperation is needed to build trust in the global digital economy and build resilience in GVCs. Some G20 efforts are needed to establish frameworks that facilitate the paths for larger collaboration.

The G20 should create a new regulators’ forum specifically oriented to regulatory cooperation, bringing regulators into more frequent interaction with each other for peer learning and information exchange. The new R20 would represent a global initiative in recognising the importance of cross-border dialogue and cooperation among domestic regulatory agencies and standards-setting agencies.[23] It would set a model for other regional and global institutions in finding ways to transition to the digital economy, with greater interoperability between trading partners’ regulatory regimes. The World Bank has long championed a ‘knowledge platform’ approach to boost the regulatory cooperation on services,[24] and the Asian Development Bank has made similar recommendations for digital services.[25] These and other inter-governmental institutions could be invited to join the forum.

Utilise the WTO to build a formal multilateral framework for digital trade and economic cooperation

Some G20 members have hesitated to embrace efforts by the WTO to develop new governance arrangements for e-commerce/digital trade; a few appear actively hostile to such developments. As the 2023 G20 chair, the world looks towards India to grasp its opportunity for a leadership role in the WTO.

India was the first country to publish results under UNCTAD’s groundbreaking pilot survey on the measurement of digital trade in 2016–17.[26] ICT-enabled services exports totalled US$89 billion, of which 63 percent was computer services, 14 percent was management and administration services, and 11 percent was engineering and R&D services. UNCTAD noted that ‘digital delivery’ is particularly important for ‘small enterprises’. Indian e-commerce companies were already targeting global markets, especially for creative and cultural services such as film, music, and e-books. India’s services exports have driven the country’s overall export growth. In 2021–22, exports of India’s software services increased by more than 17 percent to US$157 billion, of which computer services accounted for over two-thirds.[27] IT-BPO services comprise over 60 percent of India’s services exports.[28]

As a digital giant and a representative of the Global South, India is one of the few economies well positioned to lead a G20 return to multilateralism in digital commercial policymaking. This would require a G20 statement signalling increased G20 priority to making multilateral progress on digital trade rulemaking as well as digital regulatory cooperation and international digital standards development.[29] This would entail a two-pronged approach in the WTO.

First, the G20 must demonstrate an intensification of joint energy and engagement in the processes associated with the WTO Work Programme on E-Commerce (see Annex). The G20 should focus on finding joint solutions to bridging digital divides among and within WTO members, especially developing economies and MSMEs, including their access to digital GVCs. This involves evidence-based discussion of the benefits and inconveniences of the moratorium on customs duties on e-transmissions. A review of public statements by industry groupings[30] suggests that continued extension of the moratorium is widely seen by businesses, whether global or local, big or small, to be a good thing for ongoing digital innovation, productivity enhancement, and export competitiveness. There are dangers to ignoring the high level of international business consensus on this matter. All G20 members need to ensure that they engage in active consultation with domestic SME and MSME players that are increasingly dependent on the import and export of e-transmissions.

Second, taking the WTO into the digital age requires more active support from the G20 for potential digital rulemaking in the WTO, including via the JSI on E-Commerce (see Annex). There is evidence that rulemaking is important for digital trade to flourish. A recent APEC study[31] found that the adoption of specific digital trade provisions increased total flows of digitally ordered and digitally delivered trade by between 11 percent and 44 percent in successive years. Flows of digitally delivered services increased by 2.3 percent for every additional digital trade provision that came into force between two APEC trading partners. This translates into digital trade provisions coming into force over 2000–2018, adding around US$40 billion or nearly 3 percent to APEC digital trade flows in 2018.

Participants in the WTO JSI have come together on much that will facilitate e-commerce but are yet to clinch the deals required to enable and promote the flow of data, addressing issues relating to cross-border data flows, data localisation, and source code. This may require the development of new sets of options in the search for appropriate, potentially multilateral ‘landing zones’. Options with possible flexibility that help address legitimate public policy objectives or allow transition periods associated with capacity building efforts[32] may help provide such landing zones for solutions that are acceptable to all.

There is also a need for constructive work on the institutional setting for any resulting set of new trade rules. The simplest solution is for all G20 members to participate, paving the way for a multilateral agreement. The next best option is for all G20 members, including those not currently ready to join the JSI, to signal clear support for integration of the JSI outcome into the multilateral framework. A global G20 show of support for the WTO would help significantly reduce the ongoing fragmentation of the global digital economy.

Annex: WTO Work Programme on E-Commerce and WTO JSI on E-Commerce

Work Programme on E-Commerce

As reported on the official WTO website, the Work Programme on E-Commerce was adopted by the WTO General Council in September 1998. Four WTO bodies were tasked with exploring cross-cutting issues in the relationship between e-commerce and existing WTO agreements (Council for Trade in Services; Council for Trade in Goods; Council for Trade-related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights; and Committee on Trade and Development). The General Council had the role of examining a provisional moratorium on customs duties on e-transmissions (also adopted in 1998) and providing recommendations for further action. Ministers reviewed the Work Programme at subsequent Ministerial Conferences, noting the work undertaken and instructing the various bodies to continue the work. Ministers regularly agreed to continue the practice of not imposing customs duties on e-transmissions until their next ministerial conference.

One can distinguish two periods of activity under the Work Programme. First is the period 1998–2015. After the initial flurry of proposals and discussions, there was a long period of relative quiet. This changed in the second period, around the time of the 10th WTO Ministerial Conference (MC10) in Nairobi in 2015. From then, the discussion was revived and expanded until WTO MC12 in Geneva in June 2022, where Ministers agreed to intensify discussions on the moratorium and instructed the General Council to hold periodic reviews “including on scope, definition, and impact of the moratorium”. Some WTO members expressed views that the Moratorium was meant to be provisional, that there is now sufficient information on how e-commerce is functioning, and the moratorium should be ended because it limits WTO members’ discretion in the field of customs policy, and deprives members, in particular developing and least developed members, of customs revenues. Ministers agreed in Geneva to maintain the current practice of not imposing customs duties on e-transmissions until WTO MC13, which will take place in February 2024. They agreed that the moratorium will expire on 31 March 2024, unless Ministers or the General Council decide to extend it.

JSI on E-Commerce

In December 2017, in the margins of WTO MC11 in Buenos-Aires, a group of 71 WTO members launched a Joint Statement Initiative (JSI) on E-Commerce to initiate exploratory work towards future WTO negotiations on trade-related aspects of e-commerce. The talks started in 2019 with 76 participants. There are now 89 participating members which account for more than 90 percent of global trade with representation from various geographical regions and levels of development, committed to ensuring that the JSI remains balanced, inclusive and meaningful to consumers and businesses alike. The vast majority of the G20 are participating, with the exceptions of India and South Africa.

In December 2022, the participants issued a consolidated text with convergence on ten articles: paperless trading; e-contracts; e-authentication and e-signatures; unsolicited commercial e-messages; online consumer protection: open government data; open internet access; transparency; cybersecurity; and e-transactions frameworks. Participants committed to intensify negotiations, aiming to conclude by December 2023, or at the latest in the margins of WTO MC13. Provisions that enable and promote the flow of data, were identified as requiring further work, such as cross-border data flows, data localization, and source code. Participants are also continuing discussions on making permanent the ban on customs duties on e-transmissions.

Work is also needed on the final institutional setting, ie whether such an agreement, if and when finalised, will be part of the WTO. These negotiations are seen by many G20 members as a tool that will be part of the multilateral framework for digital trade and economic cooperation. The outcome could comprise the first ever global rules on digital trade, binding some existing rules and initiating some new ones.

Jane Drake-Brockman is Visiting Fellow, Institute for International Trade, University of Adelaide.

Pascal Kerneis is Lecturer in European Law, University Paris Saclay.

Harsha Vardhana Singh is Councillor, Global Trade Observer.

Badri Narayanan Gopalakrishnan is Non-Resident Senior Fellow, National Council for Applied Economic Research and Centre for Social and Economic Progress.

Rajat Kathuria is Dean and Professor of Economics, Shiv Nadar Institute of Eminence.

Manjeet Kripalani is Executive Director, Gateway House.

This policy brief was first published by T20 India. Download the brief here.

References

[1] India’s experience, along with that of other developing G20 economies, have provided numerous case studies on addressing this challenge and on the associated needs for both domestic and global policy development and regulatory cooperation. India’s Open Network for Digital Commerce (ONDC), for example, is an open-source network designed to enable buyers and sellers nationwide to transact with each other irrespective of the e-commerce platform on which they are registered. ONDC’s vision is to move the diverse Indian bazaar of goods and services online, thereby democratising digital commerce for buyers and sellers/service providers across sectors. The objective is to fuel the next wave of economic growth by helping overcome the challenges and barriers to adoption of digital commerce through the core attributes of interoperability, unbundling, and decentralisation.

[2] OECD, “Services Trade Restrictiveness Index: Policy Trends up to 2023,” 2023.

[3] APEC, “Policy Brief on Services and Structural Reform,” December 2022; OECD, “Policy Trends up to 2023.”

[4] Open Network for Digital Commerce/McKinsey and Company, “Democratising Digital Commerce in India,” April 2023.

[5] WTO, “New Data Reveals Regional Variations in Digitally Delivered Services Trade,” April 2023.

[6] International Trade Centre, “SME Competitiveness Outlook: Connected Services, Competitive Businesses,” September 2022.

[7] Noshir Kaka et al., “Digital India: Technology to Transform a Connected Nation,” McKinsey Global Institute, 2019.

[8] Telecommunications Regulatory Authority of India, “Press Release No. 31,” March 31, 2023.

[9] Insider Intelligence, “Real-Time Payment Transactions by Country,” 2023.

[10] Insider Intelligence, “Real-Time Payment Transactions by Country”.

[11] Rajat Kathuria et al., “Economic Implications of Cross-Border Data Flows,” Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations, 2019.

[12] Badri Narayanan Gopalakrishnan, “Analyzing the Impact of Cross-Border Digital Transmissions on MSME Sector in India”, Working Paper, 2023.

[13] MSME data sources include the OECD Inter-Country Input-Output (ICIO) tables, World Bank Enterprise Surveys, the Indian government’s MSME census datasets, and national sample surveys.

[14] Indonesian Services Dialogue, “Digital Adoption and Dependency on Digital Goods and Services in MSME: A Survey of MSME in Java and Bali (Final Report),” 2021/2022.

[15] ISD, “A Survey of MSME in Java and Bali”.

[16] ISD, “A Survey of MSME in Java and Bali”.

[17] OECD, “The Case for the E-Commerce Moratorium,” May 2022; Hosuk Lee-Makiyama and Badri G. Narayanan, “The Economic Losses from Ending the WTO Moratorium on Electronic Transmissions,” ECIPE, August 2019.

[18] Gopalakrishnan, “Analyzing the Impact of Cross-Border Digital Transmissions on MSME Sector in India”.

[19] Subrata Das and K. Das, “Factors Influencing the Information Technology Adoption of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSME): An Empirical Study,” International Journal of Engineering Research and Applications 2, no. 3 (2012).

[20] Toolkit for Measuring the Digital Economy, G20 Argentina, 2018, https://www.oecd.org/g20/summits/buenos-aires/G20-Toolkit-for-measuring-digital-economy.pdf

[21] OECD/WTO, “Services Domestic Regulation in the WTO: Cutting Red Tape, Slashing Trade Costs, and Facilitating Services Trade,” November 2021.

[22] WTO, “Joint Statement Initiative: Reference Paper on Services Domestic Regulation, INF/SDR/2,” November 2021.

[23] Candidates for greater international regulatory dialogue include cryptocurrencies and blockchain.

[24] Bernard Hoekman and Aaditya Mattoo, “Services Trade Liberalization and Regulatory Reform: Re-Invigorating International Cooperation,” CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP8181, January 2011.

[25] ADB, “Unlocking the Potential of Digital Services Trade in Asia”.

[26] UNCTAD, “India’s Digital Services Exports Hit $83 Million Says News Survey,” 2018.

[27] India Brand Equity Foundation, “Exports: Services,” January 2023.

[28] Government of India, “Economic Survey 2022-2023,” Ministry of Finance, 2023.

[29] See “Why International Digital Standards Development Matters for Interoperability of Cross-Border Trade in Digital Services,” T20 Policy Brief.

[30] See the global industry statement signed by 100 business groupings around the world in support of the extension of the moratorium in June 2022. Another example has been reported by the Jakarta Post.

[31] APEC. “Economic Impact of Adopting Digital Trade Rules: Evidence from APEC Member Economies,” March 2023.

[32] UNCTAD, “What is at Stake for Developing Countries in Trade Negotiations on E-Commerce? The Case of the Joint Statement Initiative,” 2021.