On 30 November, The International Monetary Fund (IMF) decided to add the Renminbi (RMB) as the fifth currency in the basket of currencies that determines the value of the special drawing rights (SDR). This is the first adjustment to the SDR basket in 15 years.[1] The RMB’s weight in the basket will be the third largest, ahead of Japan’s Yen and the British Pound. The RMB’s inclusion will be operationally effective on 1 October 2016.

What led to this decision? And what does this mean for the IMF, China and global markets?

There are presently four currencies in the basket: the U.S. dollar, Euro, Pound and Yen. These are weighted on their relative importance in trade and exchange markets—namely being among the top global exporters and being judged as freely usable currencies.

Of these two, China had already met the export criterion at the time of the last SDR review in 2010. Since then, on many indicators, China has become at least the world’s third-largest exporter, and has significantly reduced the gap with the world’s top two exporters, the U.S. and the Euro area.

The issue at the 30 November IMF review, therefore, focused on the RMB being a freely usable currency.

Under the freely usable criterion, there are two essential requirements; the currency must be widely used to make payments for international transaction and be widely traded in the principal exchange markets. It is important to note that capital account convertibility is not necessary.

In this context, it has helped that there has been much greater two-way and market flexibility of the RMB and as a result the IMF recently assessed that that the currency is no longer misaligned.[2]

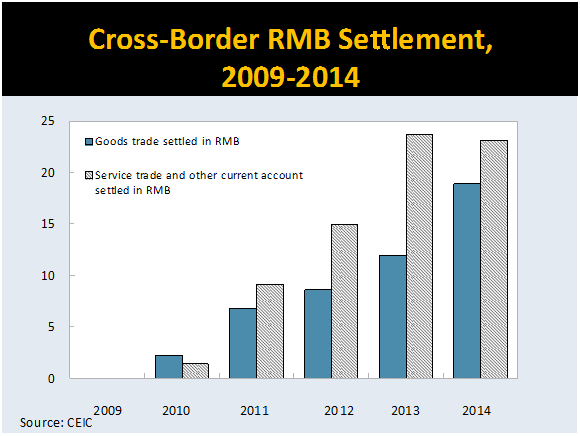

Certainly, a broad range of indicators show increasing international use of the RMB, albeit from a low base, since the last SDR valuation review. As China’s trade has grown, settlements in RMB have followed—reaching 20%-25% of China’s trade and current account (chart); and 20%-30% of foreign direct investment. China’s outward investments are also now in RMB.

Given China’s external trade and now rising financial integration, it is not surprising that offshore and onshore RMB trading activity has rapidly grown. This includes at least seven international financial centers and 15 offshore clearing banks. And the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) has developed bilateral local currency swap lines, with over 30 central banks.

As a result, the RMB ranks higher on key indicators of a freely usable currency. Among these, RMB-denominated letters of credit (LoC) for trade finance have risen to be the third largest, behind the U.S. dollar and the Euro.

Looking ahead, markets will likely expected an integration of onshore/offshore markets, with the convergence of their rates, and making the RMB more fully convertible, which would be the road to the renminbi becoming a reserve currency.

In this context, there was a lot of attention this summer over the differentials between the onshore and offshore RMB exchange rates, and the factors that explain its persistence. Of course this can reflect capital controls but also differences in the investor composition between these two markets and the different sensitivities of these investors to the same externalities. Policy-wise, further steps to lower restrictions on onshore foreign exchange trading and barriers to cross-border RMB movements will tend to lower the level and volatility of the differential.

However, further steps to make the capital account more open and the RMB more fully convertible need to be carefully sequenced with other policies — maintaining macroeconomic stability, deepening financial reforms, and removing implicit guarantees that have in the past distorted the pricing of capital. The next steps include building the financial infrastructure and broadening the liquidity and depth of its equity and bond markets.

But will it impact the markets? There is no direct reason to expect a market impact. The SDR exists only on the books of the IMF, and the SDR reserves account for a small fraction of global reserves. However, it denotes confidence about China’s policy framework and the use of the RMB in the IMF’s lending operations and the use by IMF members to obtain freely usable currencies in exchange for their SDR holdings.[3]

What does all this mean for the Indian rupee? From India’s perspective, there should be no short term market implications but, over the medium term, it could be another driver of India’s ongoing external reforms. As India’s external trade and capital opening rise, as they should in a carefully sequenced way, the rupee will integrate more fully with global financial markets. From the IMF’s perspective, opening the SDR basket to the renminbi, confirms the IMF intent to bring emerging markets into operational issues and decisions related to the global monetary system, and the inclusion of the RMB is likely just the first step toward bringing other emerging market currencies into the SDR.

Anoop Singh is Distinguished Fellow, Geoeconomics Studies at Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. He is currently an adjunct faculty member at Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, Singapore, and at Georgetown University, Washington, D.C. He was the managing director and head of regulatory affairs, Asia Pacific, for JP Morgan until mid-2015. Before that, at the International Monetary Fund, he was director of the Asia and Pacific Department (2008-13) and director of the Western Hemisphere Department (2002-08).

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2015 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited

References

[1] The International Monetary Fund, Review of the Method of Valuation of the SDR, 13 November 2015, <http://www.imf.org/external/pp/longres.aspx?id=5002>

[2] The International Monetary Fund, People’s Republic of China 2015 Article IV Consultation—Press Release; Staff Report; and Statement by the Executive Director for The People’s Republic of China, August 2015 <http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2015/cr15234.pdf>

[3] Factsheet, The International Monetary Fund, Special Drawing Right (SDR), 30 November 2015 <http://www.imf.org/external/np/exr/facts/sdr.htm>