Many commentators have noted the change in mood and atmosphere in Beijing from when it hosted the Summer Olympics in 2008. On that occasion, Beijing was looking for approbation from the outside world, whereas this time its predominant message could be paraphrased as ‘we are what we are, now make room for us’. While in the run-up to the 2008 Olympics, Beijing ran a mass programme to teach its residents basic English so they could help foreigners in need, this time English words on subway signs and route maps have been replaced with Pinyin that few foreigners can follow.

Russian President Vladimir Putin showed up and presented a ‘united front’ with Chinese President Xi Jinping as the latter opened the Games, even as he was hit by a diplomatic boycott by some Western democracies citing human rights violactions in Xinjiang. The boycott was joined by India when China chose Qi Fabao – PLA regiment commander who was wounded in the assault on Indian troops in the deadly June 2020 Galwan clashes – as one of its Olympic torchbearers.

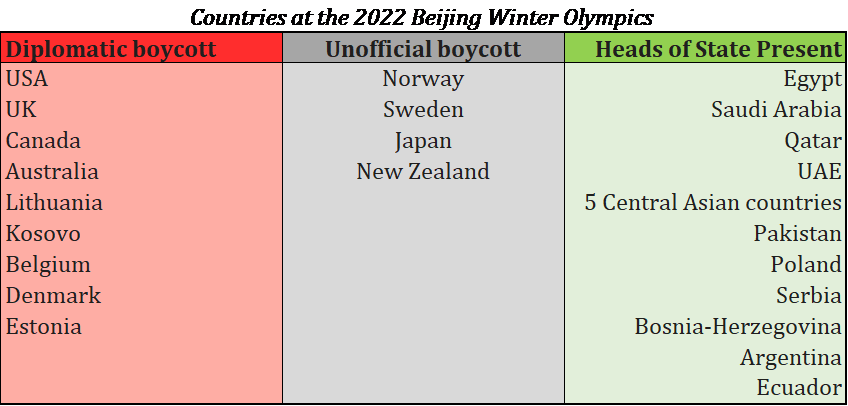

While the U.S., UK and Canada led the western diplomatic boycott, others supported it by choosing not to send diplomatic representatives while not officially describing it as a boycott. The royals of Norway and Sweden, normally present at Winter Olympics, dropped this one.

At the other end of the scale, many heads of state were present at the opening ceremony, whose roll call looks like an autocrats’ party although some leaders of democracies were present as well: apart from Putin they included various heads of state, as seen in the table below.

Helping Beijing countervail the Western diplomatic boycott is Putin, whose Feb 3 summit with Xi, resulted in a “Joint Statement on the International Relations Entering a New Era and the Global Sustainable Development” just before Xi opened the Games, and as Russian troops gathered on Ukraine’s borders creating a tense situation in Europe. The statement, which vows there are “no limits” to the Sino-Russian relationship, dwells at great length on both nations’ grouses against the U.S. and the liberal world order. In a way, the Xi-Putin summit has brought the wheel around full circle from the Nixon-Mao summit – also held in Beijing exactly half a century ago in 1972 – which triggered a geopolitical earthquake by ending the Sino-Soviet alliance and ushering in an era of Sino-U.S. cooperation.

Of note to Delhi is that the joint statement takes aim at Indo-Pacific policies adopted by the Quad countries. It pointedly juxtaposes its preference for the older term ‘Asia-Pacific’ to refer to the region as opposed to the U.S. use of ‘Indo-Pacific’ – Beijing always uses the older term, perhaps because ‘Indo-Pacific’ lends geopolitical salience to India.

These geopolitical developments are of some concern to New Delhi. Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan met Xi two days after Putin, and the ensuing joint statement carved out a common position on Kashmir: “The Chinese side reiterated that the Kashmir issue … should be properly and peacefully resolved based on the UN Charter, relevant Security Council resolutions and bilateral agreements. China opposes any unilateral actions that complicate the situation”. Relevant Security Council resolutions appear to be a reference to UNSC Resolution 47 calling for a plebiscite in Kashmir, which has long since lapsed but is routinely sought to be resurrected by Pakistan, while ‘unilateral actions’ looks like a reference to India’s 2019 decision to end Jammu and Kashmir’s special status.

This should be read in conjunction with the two-front threat building up across India’s land borders, as Beijing refuses to disengage from the two-year-old military standoff across the Line of Actual Control. Alongside Imran Khan was able to wangle an invitation to Moscow later this month – the first visit by a Pakistani Prime Minister in 23 years – even as Moscow is reported to be keen to sell arms to Pakistan. Questions might arise about how Pakistan could pay for arms purchases from Moscow given its parlous external debt situation. But Islamabad tends to put the needs of its military first and its economic and social situation later. As an example, during 2020-21, the year Pakistan was hit by Covid, it allocated $7.85 billion for defence – a 12% increase over the last year – and a mere $151 million for health.

The current consensus view is that a Russia faced by Western sanctions will become more dependent on China for economic, diplomatic and ideological support. Is it a good strategy then for Delhi, which is facing off with Beijing across the Himalayas, to be so dependent on Moscow for the majority of its arms supplies? Memories of the 1971 Indo-Soviet friendship treaty tend to cast a warm glow of sentiment across the Indian mind. But it may be apposite to remember 1962 as well, when the Soviet Union suspended supplies of MiG-21 fighters to India at a time that has been called India’s ‘darkest hour’ during its war with China. It was the Americans which supported Delhi with arms and by sending the aircraft carrier USS Kitty Hawk into the Bay of Bengal, while leaning on Islamabad not to open a second front against India.

This may be a good moment, therefore, to reduce dependence on Russian arms – both by moving faster to indigenise defence production and by diversifying arms imports to a greater degree.

The China-Russia relationship has seen many ups and downs since the founding of the People’s Republic of China. But Putin’s standing by Xi as some Western democracies mounted the diplomatic boycott of the Beijing Winter Olympics, as well as their joint statement indicating Beijing’s and Moscow’s willingness to work together to forge a new world order, suggest an enhanced level of partnership that hasn’t been seen for a long time – one that comes closer to being an informal alliance than a mere transactional relationship. Both see American power as being unjust and in decline; both wish to carve out spheres of influence stretching beyond their geographical boundaries – Russia in Ukraine, Kazakhstan and other post-Soviet states, China in East and South Asia.

China and Russia could form the nucleus of a powerful new axis that draws in other states such as Pakistan, Turkey, Iran and North Korea.[1] Regardless of how the Ukraine situation plays out in the coming days, that is likely to be the principal challenge confronted by the West-led liberal order over the next decade or so.

Swagato Ganguly is Adjunct Fellow, Gateway House, and Consulting Editor, Times of India.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2022 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References:

[1] https://www.hindustantimes.com/opinion/democratic-quad-vs-china-s-quad-101626615380664.html