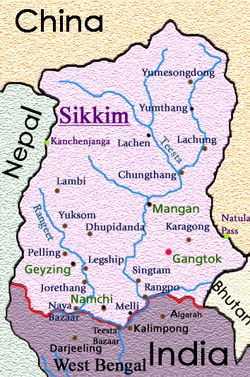

The spot in front of the massive iron grill gates of the Nathu La Pass in Sikkim is unique. A few feet to the east is the border with China’s Tibet Autonomous Region. To the west is Nepal, and further east is Bhutan. The point at which China and India meet is divided by the famous barbed wire leading to a rock, a reminder of the 1967 battle between the two armies. Sentries stand at the two check-posts. At 14,140 feet above sea level, Nathu La is cold, minus 5 degrees Celsius, even in the spring. Some two-dozen intrepid Indian tourists have arrived at the spot; they are overwhelmed by its significance. [1]

Nathu La is located on the old silk route between India and Tibet, a natural trading path. After China’s annexation of Tibet in 1959, the route was closed. It re-opened for India-China trade in 2006, but closed again in 2020, when Chinese forces entered Indian territory in Galwan, and India blocked all border points for trade. The incident led to an increased public awareness of India’s borders. There’s no tamasha at this check post, unlike the Wagah border, but there is much of the beauty of India’s second smallest state, Sikkim, to see.

The history, culture and geography of Nepal, Tibet and Bhutan carry over into Sikkim, visible in its streets, in its citizens, in its outlook. The Buddhist endless knot motif is on the railings of the pavements, the bhaku is worn by the women every day and the serenity of the Buddha is in the mountain air. The benefit of stability – Sikkim had one chief minister, Pawan Kumar Chamling, for 25 years till 2019, and the current Prem Singh Tamang is likely to win a second term – ensured that development was a priority. The outcome is a self-sufficient, agrarian state very much in sync with its habitat and with an emphasis on biodiversity, 100% organic farming and tourism. The egalitarian society, just 6 lakhs, has a high literacy rate of over 80%, and per capita GDP has crossed $6,000, twice the Indian average.

Environmental protection and cleanliness is a way of life, and enforced. Gangtok city is the ideal Indian hill station, with none of the litter associated with Indian mountainsides. A visitor knows immediately when they have crossed over from the decrepit highways of Bengal into Sikkim: the steep roads and hairpin bends built by the Border Roads Organisation, are smooth and safe.

The interest in Sikkim has been largely romantic. It is often described as Shangri La, an other-worldly abode for trekkers seeking to climb the Kanchenjunga range in the state’s northwest. In the last five years, however, as interest and investment in India’s northeast has been activated and the wealth of India’s middle classes have been on the rise, Sikkim too is getting some five-star attention. All of mainland India is present in Sikkim, every consumer brand, every financial service, from Raymonds and Fabindia to State Bank and ICICI.

The lush tea estates of the state are converting their homesteads into luxury spaces and local groups like Mayfair and international ones like the Taj, have spectacular properties in Sikkim. The Taj group alone has developed 29 new properties in India’s east since 2019 and has plans for 17 more for the next three years, including one in Tawang, Arunachal Pradesh. Tourists come from Mumbai, Gujarat, Delhi, Bengal, Bihar and beyond for the beauty, the healthy air, for trekking and for destination weddings.

Sikkim will go to the polls on April 19, to select its new legislature and to choose the single member it will send to India’s Parliament. In late March, there isn’t much sign of campaigning. A few banners of the incumbent Sikkim Krantikari Morcha (SKM) are being hung on the roadsides and markets. The BJP, however, has ended its alliance with SKM and is going alone in the state for the first time. As it proceeds with aggressive door-to-door campaigning and promises full implementation of central government schemes, it may find that in Sikkim, everything is still local.

Manjeet Kripalani is Executive Director, Gateway House.

This blog was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

Support our work here.

For permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

©Copyright 2024 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorised copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References

[1] Enchanted Frontiers by Nari Rustomjee, pg. 233, 245. https://archive.org/details/dli.pahar.3398/page/232/mode/2up?view=theater