The dramatic turn of events in Bangladesh since August 5 has shifted the geopolitical tectonic plates of the subcontinent. Just as it seemed like Asia was largely sheltered from the deadly wars in West Asia and the European region, the same forces arrived at India’s immediate border in the form of the ouster of Sheikh Hasina, the former Prime Minister of Bangladesh.

The primary reason for the riots that led to regime change was a leader who was not responsive to the issues of jobs and livelihood for her young population. And certainly, anti-incumbency after 15 years of virtual one-party rule was a factor.

But there were also a variety of players stirring trouble in the cauldron of unrest. Opposition parties, religious extremist groups, NGOs within and without Bangladesh, meddlesome great powers and small nations.

In addition to the disgruntled students who took to the streets to protest an unfair quota law, were the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), the main opposition led by Khalida Zia which has boycotted the last two elections. Inserted alongside was the Jamaat-e-Islami, the largest Islamic party in Bangladesh, which is averse to the Awami League’s secular credentials.

Pakistan, always looking to prove that the two-nation theory, on which its own foundation was built, as however illegitimate when it comes to the creation of Bangladesh, was aligned with the BNP and Jamaat. Its spy agency the ISI has been active in Bangladesh for decades, and Hasina says openly that it joined hands with the BNP in her ouster.

Within Bangladesh is the outsize role played by NGOs, local and international. Bangladesh was built with the support of civil society. Its contribution to the world is a successful micro-finance model, built by Mohammad Yunus who began Grameen Bank in 1983. Yunus is now the country’s new chief advisor, replacing Hasina. There is Bangladesh Rehabilitation Assistance Committee (BRAC), founded in Bangladesh in 1972 by Sir Fazle Hasan Abed[1] with a development model that has made it the world’s largest and now most influential NGO. Both these dominate the development landscape in Bangladesh.

The most influential foreign NGO has been the U.S.-headquartered Ford Foundation, in the country since 1972 and now blended into the Bangladesh Freedom Forum[2], a grant-making organization. The Foundation’s head in Dhaka had head-of-state-like status. It often hired away the most promising officers of the government, depleting the talent of a young, underdeveloped country. Through various other NGOs like Open Society, Care and Save The Children, U.S. NGOs dominate the Bangladeshi landscape. An official list of foreign NGOs in Bangladesh shows that the U.S. has the most, at 81, followed by the UK at 45 and Japan at 19; India scores poorly at just two.[3]

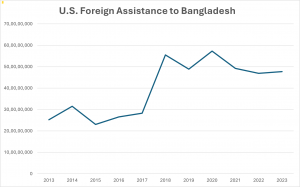

Interlinked with the above is the role of the U.S., which unlike China does not build infrastructure in developing economies; instead, it funds civil society efforts. These are essential, capacity-building efforts, but they also carry with them insidious elements which impose the promotion of “human rights and democracy.” Those destabilizing efforts have been in play for the past 75 years in South Asia, and are now visible and intense. In the decade up to 2023, U.S. foreign assistance to Bangladesh nearly doubled to $477 million (see chart).

The rise of U.S.-China strategic rivalry over the past decade, particularly in Asia, is evident in Bangladesh, whose geopolitical positioning has been enhanced by the $12 billion investment by China in that nation. It has made the Bay of Bengal, now part of the Indo-Pacific, an area of potential contestation. In particular is Sheikh Hasina’s accusation of the U.S. wanting to build a military base in the offshore island of St. Martin’s, which she says she declined.

The U.S. has also weaponised its visa-issuing powers to chastise Bangladeshi forces. In 2021, it issued visa restrictions on top officers of the elite Rapid Action Battalion (RAB) stating human rights abuses[4] as part of Bangladesh’s war on drugs. In March 2023[5], it left Bangladesh out of the Democracy Summit – and, mysteriously kept Pakistan in. The U.S. media and even think tanks, fell in, unquestioningly, with these policies, saying “the Bangladeshi government continues to ignore U.S. pressure.”[6] Top regime-change architect Victora Nuland, helpfully reiterated Bangladesh’s anti-democratic mood during her visit to Dhaka in March 2022. She will certainly have had the support of diaspora members, who like most that live away from their homeland, tend to be more conservative than secular.

The role of the Bangladeshi diaspora is a factor. As in many developing countries, the diaspora is influential in their homeland and Bangladesh is no exception. While overseas, the diaspora adopts the policies and terminologies of their host country in favour or against their home country. [7] The U.S. hosts an estimated 500,000[8] Bangladeshis currently – many of whom are the children of political and military leaders of all political shades. They are starting to enter politics in the U.S., and most vote Democrat. A similar number[9] are in the UK, the region’s former colonial power and a close confidante of the U.S. Here Bangladeshis are more established and some are in the Parliament, including Tulip Siddiq, the niece of Sheikh Hasina.

The diaspora wields influence through their political ties in the host country, but also being better off then their peers at home, through the vast remittances they send home. Bangladeshis across professions remitted $22 billion in 2022-23[10] and an estimated $24 billion in 2023-24[11] – a powerful economic lever to express political preferences.

Finally, there is India, whose overt support of Sheikh Hasina has been cited for the popular resentment expressed through the post-August 5 unabated destruction of the property and lives of the 8% Hindu population that is left in Bangladesh today. Indian agencies say they had warned Hasina of the sparks that could start a fire, but that she was confident it would blow over. Her heeding may have only postponed the inevitable.

A significant player not visible on the streets of Bangladesh are the country’s women. They were not amongst the protestors, but are among the 4.4 million women[12] working in the textile factories, where 80% of the employees are female. The industry comprises 84% of Bangladesh’s exports[13]. In the past two years, their protests have been for better working conditions and higher wages, not regime change. Their wages rose by 25% since last December to $105 a month – still half what they should receive for a living wage.

What now? There’s excitement, headiness, in the early days of an uprising, and here, with Yunus, the Nobel prize winner at the helm and two student leaders in the interim government. Alas, few such protests have led to favourable outcomes. The Arab Spring in Egypt, Occupy Wall Street in the U.S., the Umbrella Movement in Hong Kong, protests in Latin America, red and yellow shirts in Thailand, colour revolutions in eastern Europe. The only protest movement that has resulted in actual government and political participation[14] is the win of the Aam Aadmi Party in New Delhi, and that too is in the throes of adjustment and transition.

The new leadership is full of contradictions. The ousting of the supreme court chief justice and other judges, police officers – these are the very institutions that keep a country safe. Dismantling the judiciary, intimidating the police force, these do not promote stability, without which the very jobs and investment that are needed will be in jeopardy. Inflation will be a concern.

Yunus himself is 84, older than U.S. President Biden. He has used the global prestige from his Nobel prize to gain political mileage. His frequent visits to the U.S. in the last two years have coincided with the unusual and prominent negative coverage of Bangladesh and Sheikh Hasina, a nation and leader hardly ever noticed by the U.S. mainstream media. Grameen Bank has digressed from micro finance to the commercial sector with enterprises like Grameen Telecom. The work of Grameen micro loans is now being done by the government, and mainstreamed.

The Bangladeshi army has been careful not to interfere too openly. There have been a dozen successful and attempted military coups since 1975[15], which have receded over the past decade. Now Bangladesh has become the largest provider of personnel, over 7,000, to UN Peacekeeping missions[16]. These are well paid and prestigious; the army will protect this position. Unlike the Pakistani army whose many factions are now in conflict, and which has arrested one of its own recently, the Bangladeshi army does not expose itself. Military rule denies countries multilateral funding, which Bangladesh depends on, and exposes a country to sanctions. However, it was the army that played the pivotal role in the ouster of Sheikh Hasina. It was the Chief of Army Staff Waker-uz-Zaman – related to Hasina through marriage turning towards the protestors, that led to the change in Bangladesh.

India has kept its counsel these past two weeks, despite the recriminations from the new Bangladesh leaders for not supporting the protests. It will be the wisest to allow the gale of anger to blow over till the transition is complete. India’s northeast region and the volatile state of West Bengal, are both vulnerable to events and outcomes in Bangladesh. In a strange twist, in its own neighbourhood, India finds itself at odds with its new partner, the U.S., and on the same side as its Asian rival, China, with which it has common cause in keeping Bangladesh and its extended eastern flank of Myanmar, stable.

Manjeet Kripalani is Executive Director, Gateway House.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

Support our work here.

For permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

©Copyright 2024 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorised copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References

[1] BRAC is the world’s largest NGO by employee. See ‘The 15 Biggest NGOs in the World,’ Human Rights Careers, https://www.humanrightscareers.com/issues/biggest-ngos-in-the-world/; and is ranked the world’s most influential NGO. See ‘Top 10 largest NGOs in the world,’ DevelopmentAid, https://www.developmentaid.org/news-stream/post/124777/top-10-largest-ngos-in-the-world

[2] Bangladesh Freedom Foundation: Promoting Science Education,’ https://freedomfound.org/

[3] Foreign NGO List, upto June 2023, Government of Bangladesh, https://ngoab.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/ngoab.portal.gov.bd/page/4da52013_47a7_4c02_8239_ee96f040e9e8/2023-07-18-03-21-0ec7222e4c2e95c9ff72bb5dc34d7481.pdf

[4] Treasury Sanctions Perpetrators of Serious Human Rights Abuse on International Human Rights Day,’ U.S. Department of the Treasury, Dec 10, 2021, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0526

[5] Bangladesh left out of US democracy summit again,’ The Daily Star, Feb 15, 2023, https://www.thedailystar.net/news/bangladesh/diplomacy/news/bangladesh-left-out-us-democracy-summit-again-3247916

[6] Ali Riaz, ‘What the new US visa policy for Bangladesh means,’ Atlantic Council, Jun 6, 2023, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/southasiasource/what-the-new-us-visa-policy-for-bangladesh-means/

[7] Mubashar Hasan, ‘Bangladeshi Diaspora Journalists Push Back Against Democratic Backsliding at Home,’ The Diplomat, Jul 13, 2023, https://thediplomat.com/2023/07/bangladeshi-diaspora-journalists-push-back-against-democratic-backsliding-at-home/

[8] Morsheda Akhter and Philip Q Yang, ‘The Bangladeshi Diaspora in the United States: History and Portrait,’ Genealogy, Vol 7, No 4 (2023), https://www.mdpi.com/2313-5778/7/4/81

[9] ‘Bangladeshi diaspora in UK,’ Bangladesh High Commission, London, https://bhclondon.org.uk/bangladeshi-diaspora-in-the-uk

[10] Value of personal remittances in Bangladesh from 2001 to 2023, based on remittance inflow from any other country, https://www.statista.com/statistics/880700/bangladesh-value-of-remittances/

[11] Md Mehedi Hasan, ‘Remittance hit $24b in FY24, highest in three years,’ The Daily Star, Jul 2, 2024, https://www.thedailystar.net/business/news/remittance-hit-24b-fy24-highest-three-years-3646901

[12] ‘The Rise of Bangladesh’s Textile and Garment Industry: 10 Key Statistics,’ WFX, https://www.worldfashionexchange.com/blog/rise-of-bangladesh-textile-and-garment-industry/

[13] Apparel Manufacturing and Supply ‘How much of Bangladesh’s GDP is earned in the clothing industry?,’ LinkedIn, Mar 14, 2023, https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/how-much-bangladeshs-gdp-earned-clothing

[14] Rajni Bakshi, ‘AAP, Occupy and the Arab Spring,’ Gateway House, Feb 13, 2015, https://www.gatewayhouse.in/aap-occupy-and-the-arab-spring/

[15] Mohammad Jazib, ‘Military Coups in Bangladesh till 2024,’ Jagran Josh, Aug 7, 2024, https://www.jagranjosh.com/general-knowledge/military-coups-in-bangladesh-1722855785-1

[16] ‘Honoring Peacekeepers from Bangladesh & around the World,’ United Nations, May 29, 2024, https://bangladesh.un.org/en/269943-honoring-peacekeepers-bangladesh-around-world