On November 24, a group of hackers, allegedly backed by the North Korean government, launched a cyber attack on Sony Corporation’s computers in the U.S., stealing a trove of sensitive data including confidential emails, business plans, and personal details.

In the short term, the attack reportedly cost approximately $100 million to investigate, to repair or replace computers, and to take measures to prevent future attacks.[1] But it is likely to cost Sony much more—including in potential lawsuits over stolen information—in the long run, besides denting its credibility.

The case is an important reminder for Indian businesses to re-visit their strategies to deal with cyber crimes—which have increased by 40% annually during the past three years.[2] Businesses frequently do assess the risks posed by cyber crimes, but they focus on threats from the regular World Wide Web. Now, they must also pay attention to the threats emanating from the black market on the “deep web” or the “hidden” internet.

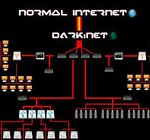

The deep web—also described as the “darknet” or the “underworld” of the cyber world—is an anonymous internet beyond the open traffic of the regular internet. Its websites do not figure in the extensive results of conventional search engines such as Yahoo or Google. An exact estimate of data flows on the deep web is not available, but in 2001 researchers in the U.S. had speculated that it contained 7,500 terabytes of information, as compared to 19 tetrabytes on the regular internet.[3] IT professionals in India estimate that the deep web now accounts for approximately 70% of online traffic.

The technology driving the deep web is ‘The Onion Router’ (TOR), developed initially by the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory for confidential communications. The TOR encrypts and transmits user traffic through several different computers in multiple layers. This allows individual users to hide their internet protocol (IP) addresses—a numerical identifier assigned to a computer or device logged on the internet—and gives them the freedom to remain anonymous in any online activity.

This technology has been widely used by security agencies in the West, particularly in the U.S., as well as by others, including political protestors in Egypt, Hong Kong, and other countries. Journalists have used it too—for example, in April 2014 the Reporters Without Borders non-profit group signed an agreement with TOR to ensure greater privacy and bypass surveillance by security agencies.

However, the misuse of the technology by cyber criminals to create a thriving black market on the deep web since 2011—the year the Silk Road market site emerged—is now a major challenge, since the anonymity offered by the deep web makes it even more harmful than the regular material black market.

To breach Sony’s servers, for example, the hackers used a virus which was available for distribution in the deep web’s black market. The stolen sensitive data is likely to find its way to the same market, where cyber criminals already sell such data extensively to create forged identities and commit banking frauds. Reliable figures of the value of these transactions are not available.

Payments in this market are, expectedly, made in crypto-currency such as the Bitcoin, which has no central issuing authority and permits anonymous transactions. In 2013 media reports had estimated that 12 million Bitcoins were in circulation; [4] at present, one Bitcoin is worth $300-335.

The deep web’s black market is a cornucopia of dark products, offering much more than stolen personal data and malicious software. Items traded here include sensitive trade secrets, stolen bank and credit card information, firearms, and controlled substances and narcotics which cannot be bought in an open market. Services offered include contract killing, drug peddling, and money laundering.

Like regular websites and companies, the deep web has entities too. Silk Road was one such site on the black market, with a majority of sellers offering drugs, pornography, and guns. Its activities were dominated by buyers and sellers from North America and Europe, but the site also had users from India.

Silk Road was shut down in 2013 by the U.S. government when it arrested the site’s owner, Ross Ulbricht, a U.S. citizen. Between 2011 and 2013 the site generated revenues worth $1.2 billion, while the various sellers who used the site had earned commissions worth approximately $80 million in total.[5]

This thriving black market on the deep web has, in turn, contributed to the growth in cyber crimes across the world. American internet security firms McAfee and Symantec estimate that the annual cost of cyber crimes to the global economy is between $113-575 billion.[6] [7] India incurs a fraction of this cost—around $4 billion—but it is a lot for a developing, unprepared country.[8]

Although the financial implications of the deep web’s activities, which can be quantified with some number crunching, cause enormous harm, it is the implications for national security that are far more serious.

For terrorist groups, always looking for new technologies, the deep web’s black market is an ideal platform to purchase arms and smuggle drugs, and to raise funds.[9] No hard evidence is available at present of such activity, but terrorist groups are clearly making efforts to explore this avenue.

In July 2014, a post on a WordPress blog, purportedly linked to an Islamic State sympathiser, mentioned how Silk Road and Bitcoin can be used to purchase weapons and sell narcotics.[10]

But it seems that everyone else, legitimate or illegitimate, is benefiting from the deep web too. For saboteurs and hackers, it provides easy access to malicious software. For intelligence agencies and businesses, it is a useful tool for espionage—for example, multinational corporations can hack into the servers of rival companies to mine strategic commercial information, without ever revealing their IP addresses.

In the West—especially in the U.S.—law enforcement agencies have responded to the challenge of the deep web with two strategies. They try to crack its anonymity by measures such as the National Security Agency’s Project Honey Pot,[11] which collects information about IP addresses. And they also extensively use the deep web to pursue leads on cyber crime and communicate with undercover sources.

Insulating the legitimate internet community from the ill-effects of the deep web is a challenging task. It requires sophisticated technical expertise to crack anonymous communications. Incarnations of Silk Road, for example, have survived despite the original being shut down last year by the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation—in no time a new avatar, Silk Road 2.0, appeared. This too was shut down in October 2014 when the U.S. and Europol cracked down against the deep web’s black market.[12] Yet, within hours, spawns of the Silk Road went online—some of them even selling items eschewed by Silk Road, such as child pornography.[13]

The shadowy players of the deep web are clearly resilient in their illegal activities.

India is still to fully understand the financial and security implications of this deeper danger. The government and businesses are still grappling with the more pressing threats from the regular internet. But if it is not addressed, the deep web has the potential to expose another gap in India’s cyber security preparedness—the country’s critical infrastructure is already susceptible to cyber attacks because of outdated Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition systems, which manage India’s infrastructure operations.

Although India’s National Cyber Security Policy of 2013 stresses “building a secure and resilient cyber space” it does not even mention the threat posed by either the deep web or the Silk Road-type deep web black market.[14] Similarly, the Report on Cyber Crime, Cyber Security and Right to Privacy of the 15th Lok Sabha’s Standing Committee on Information Technology does not mention these risks, though it examines in detail the threat posed by cyber crime.[15]

It is evident from the experience of western security agencies that countering the challenge of the deep web and its black market will require India to develop offensive cyber capabilities. With these, India can try to respond to the deep web’s nefarious activities and also trace and arrest saboteurs and cyber criminals, if necessary.

Formulating and implementing such a strategy—even though it will not provide complete security—is a long haul for India, but one which must be conceptualised.

The government’s recently set-up experts’ group for tackling cyber crime must include the deep web in its purview.[16] And it is imperative that the security establishment and business houses in India become aware and informed of the existence of the deep web.

Sameer Patil is Associate Fellow, National Security, Ethnic Conflict and Terrorism, at Gateway House.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in.

© Copyright 2015 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited

References

[1] Richwine, Lisa, Cyber attack could cost Sony studio as much as $100 million, Reuters, 9 December 2014 <http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/12/09/us-sony-cybersecurity-costs-idUSKBN0JN2L020141209>

[2] Press Information Bureau, Government of India, Setting up of Expert Study Group for tackling Cyber Crimes, 24 December 2014, <http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=114013>

[3] Bergman, Michael K., ‘White Paper: The Deep Web: Surfacing Hidden Value’, The Journal of Electronic Publishing, Vol. 7, Issue 1, August 2001, <http://quod.lib.umich.edu/j/jep/3336451.0007.104?view=text;rgn=main >

[4] Lee, Timothy B., ‘12 questions about Bitcoin you were too embarrassed to ask’, 19 November 2013, Washington Post, <http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/the-switch/wp/2013/11/19/12-questions-you-were-too-embarrassed-to-ask-about-bitcoin/>

[5] Federal Bureau of Investigation, United States Department of Justice, Criminal Complaint against Ross William Ulbricht, 27 September 2013, <https://www.cs.columbia.edu/~smb/UlbrichtCriminalComplaint.pdf>

[6] Center for Strategic and International Studies and McAfee, Net Losses: Estimating the Global Cost of Cybercrime, June 2014, <http://www.mcafee.com/in/resources/reports/rp-economic-impact-cybercrime2.pdf> p. 2

[7] Symantec, 2013 Norton Report, <http://www.symantec.com/content/en/us/about/presskits/b-norton-report-2013.pptx>

[8] Ibid

[9] Weimann, Gabriel, Terror on the Internet: The New Arena, the New Challenges (Washington DC: US Institute of Peace Press, 2006), pp. 137-138.

[10] Taqi’ulDeen alMunthir, Bitcoin and the Charity of Violent Physical Struggle, July 2014 <https://alkhilafaharidat.files.wordpress.com/2014/07/btcedit-21.pdf>

[11] Project Honey Pot, About Project Honey Pot, <https://www.projecthoneypot.org/about_us.php>

[12] Europol, Global action against dark markets on TOR network, 7 November 2014, <https://www.europol.europa.eu/content/global-action-against-dark-markets-tor-network>

[13] Digital Citizens Alliance, Post Silk Road – Another Online Drug Den Now Dominates the DarkNet, 18 December 2014, <https://media.gractions.com/314A5A5A9ABBBBC5E3BD824CF47C46EF4B9D3A76

/2251410a-790a-459c-a48a-6a4fd7dcfb88.pdf>

[14] Department Of Electronics and Information Technology, Government of India, National Cyber Security Policy-2013, 2 July 2013, <http://deity.gov.in/content/national-cyber-security-policy-2013-1>

[15] Standing Committee on Information Technology, Ministry of Communications and Information Technology, Government of India, Report on cyber crime, cyber security and right to privacy (Report no. 52), February 2014, <http://164.100.47.134/lsscommittee/InformationTechnology/15_

Information_Technology_52.pdf>

[16] Press Information Bureau, Government of India, Setting up of Expert Study Group for tackling Cyber Crimes, 24 December 2014, <http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=114013>