Since 9/11, two consecutive U.S. administrations have labored mightily to help Afghanistan create a state inhospitable to terrorist organizations with transnational aspirations and capabilities. The goal has been clear enough, but its attainment has proved vexing. Officials have struggled to define the necessary attributes of a stable post-Taliban Afghan state and to agree on the best means for achieving them. This is not surprising. The U.S. intervention required improvisation in a distant, mountainous land with de jure, but not de facto, sovereignty; a traumatized and divided population; and staggering political, economic, and social problems. Achieving even minimal strategic objectives in such a context was never going to be quick, easy, or cheap.

Of the various strategies that the United States has employed in Afghanistan over the past dozen years, the 2009 troop surge was by far the most ambitious and expensive. Counterinsurgency (COIN) doctrine was at the heart of the Afghan surge. Rediscovered by the U.S. military during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, counterinsurgency was updated and codified in 2006 in Field Manual 3-24, jointly published by the U.S. Army and the Marines. The revised doctrine placed high confidence in the infallibility of military leadership at all levels of engagement (from privates to generals) with the indigenous population throughout the conflict zone. Military doctrine provides guidelines that inform how armed forces contribute to campaigns, operations, and battles. Contingent on context, military doctrine is meant to be suggestive, not prescriptive.

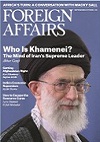

This article was originally published by Foreign Affairs. You can read the rest of the article here.

You can read exclusive content from Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations, here.

Copyright © 2013 by the Council on Foreign Relations, Inc.