This is the second in a four-part series on Partition. Read the first one here, and the next one here.

Ulhasnagar, a township in Thane district, Mumbai Metropolitan Region, located 58 km to the north west of Mumbai city, was once a Hindu Sindhi refugee camp. Today, it’s a concentration of low-slung dwellings and unplanned high-rises, spread over 13 sq km and bursting at the seams with 8 lakh people, of which less than half are Sindhis today.

Remnants of the military barracks, used during the Second World War and then converted into dormitory-style shelters for the refugees who arrived by sea in 1947-48, are still visible and many continue to live where they were born in Ulhasnagar’s Sectors 1 to 5, such as Hardas Makhijaa, a former mayor of Ulhasnagar[1]. He was four months old when he came to what was earlier known as the Kalyan Camp, from Kumbar Taluka (Larkana District), and now has his office in the very place he grew up: Camp 2, Nehru Chowk. His late father, Sanmukh Duromal Makhija, a freedom fighter, was the founder of the Sindhi newspaper, Azaadi, in 1942, and among the few who visited the Camp before bringing his family to settle there.

The most attractive aspect of the Kalyan Camp (renamed as the new township of Ulhasnagar by Governor General C. Rajagopalachari on 8 August 1949), was its proximity to Bombay—even if it had no roads, water taps, flour mills, electricity or sanitation facilities, recalls Hardas Makhijaa. Other camps, like the one in Pune, to which refugees arriving at Bombay port were also sent, were considered too far away for the city’s business and employment opportunities.

Sarla Kripalani, author of the book, Aaya Pir, Bhagga Mir and Other Sindhi Proverbs (2012), remembers her father-in-law’s nieces living in a refugee camp beyond the Kalyan Camp. “We visited them often. He told them he could help them, but he was being pragmatic when he also said that they should not depend on him entirely,” she adds. “These girls were so good at embroidery work, making achaar (pickle), papads, and mithai (sweetmeats) at home, that the younger sister would call on well-to-do Sindhi families, like the Advanis of Blue Star in the city, to sell their wares.”

According to Kripalani, Sindhi girls began working after their migration to India, and only because their families were in dire financial straits. In Sindh, most Hindu families belonged to the urban middle class, while the wealthy few were zamindars (landowners), well established merchants and bankers, or employed in key positions in the British colonial government.

In spite of displacement from their homeland in 1947-48, there were two reasons why the success of this community was almost a certainty. The Shikarpuri Sindhis from the land-bound city of Shikarpur, Sindh, in particular, had a pre-colonial global trading and financial network that extended from Astrakhan on the Caspian Sea to the Straits of Malacca.[2] It was this community of merchants and bankers who introduced and popularised the promissory note, known as the Hundi.

According to Sindhi anthropologist and author Nandita Bhavnani, “This network was dealt a blow by the Great Game (late 19th C) in Central Asia by the competing powers of Imperial Russia and Great Britain, jostling for influence. And ultimately by the Russian Revolution when many Shikarpuris were ruined, as they had large holdings of Russian roubles.”[3]

Sindhis classify themselves by their city of origin, being a mostly urban community, such as the Amils and Bhaibands from Hyderabad, Sindh; the Shikarpuris; or the Thattai Bhatia merchants (from the city of Thatta, a former capital of Southern Sindh). Sometimes, they had more generic names, like Uttaradi (a resident of Northern Sindh).

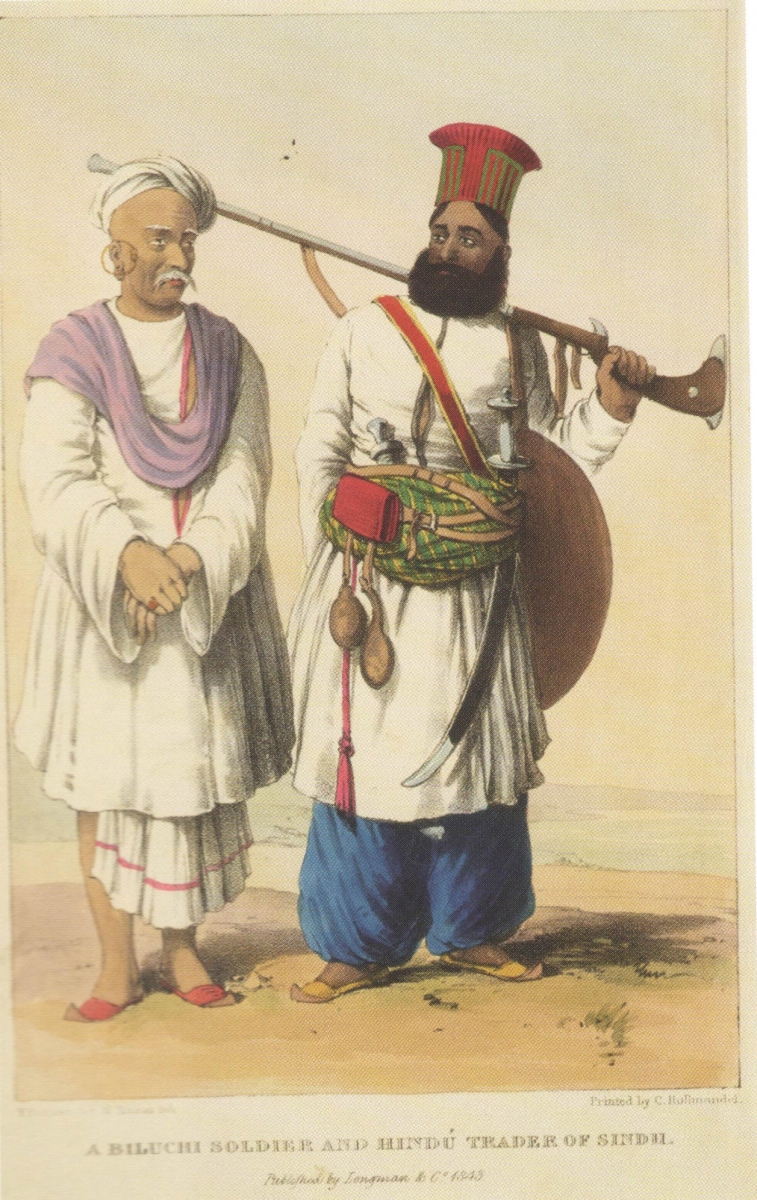

The Bhaibands (lit. ‘brothers in arms’)[4] were traders, and it wasn’t long before they built new business networks, connecting colonial port cities. Initially, with the Central Asian markets disrupted by political instability in the late 19th century, and native kingdoms impoverished by British rule, they began selling ‘Sindh work’ (ivory, wood and enamel carving, lacquer work, textiles and embroidery made by Sindhi Muslim artisans) to British soldiers, who turned out to be a ready market: they called them the Sindhworkis.

These Sindhworkis began travelling abroad from the late 1850s and early 1860s, eastwards to Canton (Guangzhou), Hong Kong, Japan, and westwards to Cairo, Malta, Gibraltar, and the Caribbean islands.[5] What is interesting is that before Partition the men travelled for two or three years, leaving their families home. Often, there was a sethia (boss), who set out with a group of young men from his family and an extended friends’ circle. They traded across the seas, meeting not just the demand for Sindh work, but selling Malta lace in Japan, and vice versa: Japanese curios in Malta.

It was this bedrock of relatives abroad, along with home-grown success stories from the camps themselves (like the owners of the Colaba-headquartered Kailash Parbhat restaurants, who once lived in the Kalyan Camp), who donated towards educational, social, business and community infrastructure within the camps.

Many of the young men left the camps to seek their fortunes abroad, only returning to collect their families. However, many have flourished in the numerous home, cottage, small, and medium scale manufacturing units, and trading businesses in Ulhasnagar that now service the Indian market.

The Sindhi influence in Bombay

Most old-timers in the city vividly remember young Sindhi boys hawking knick-knacks, trinkets, and eatables made in Ulhasnagar, on trains running between Ambarnath and V.T. Stations (now Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus). Much before Chinese goods came to be manufactured at cheap rates, the Sindhis at Ulhasnagar were making just about anything at less than half the market price.

Although, these goods were pejoratively referred to as “Made in USA” (lit. Ulhasnagar Sindhi Association), they met the demands of a vast price-sensitive Indian market–and do so even today. Trade in jeans, confectionery, pre-fabricated furniture, paper and textiles are some goods over which this township still has an edge.[6]

The Sindhis are also attributed with popularising the concept of the co-operative housing society in Bombay. According to Bhavnani, in 1914, Bombay got its first residential co-operative society at Gamdevi pioneered by Rao Bahadur S. S. Talmaki, a Maharashtrian, but Sindhi housing societies, like Navjivan Society[7], and Nanik Nivas and Shyam Nivas at Warden Road [8], which were all built during the 1950s, set up a new paradigm for community housing. Bombay had been dominated until then by the tenancy model.

It is in the spheres of philanthropy and education in Bombay that the contribution of this community is noteworthy. Much after the imprint left by 19th and early 20th-century merchants, such as Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy and the Tatas, and prior to the corporate philanthropy practised today, was the establishment from the 1950s to 1980s of Sindhi hospitals, like Jaslok and Hinduja, and educational institutions, such as Jaihind, Kishinchand Chellaram, and National Colleges.

Ulhasnagar, and the parent city of Mumbai, are rightfully called ‘mini Sindh’ because this city is today the headquarters of a community with a worldwide presence.

Sifra Lentin is Bombay History Fellow at Gateway House.

Nandini Bhaskaran is Copy Editor at Gateway House

This is the second in a four-part series on Partition. Read the first one here, and the next one here.

This article was exclusively written for Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. You can read more exclusive content here.

For interview requests with the author, or for permission to republish, please contact outreach@gatewayhouse.in or 022 22023371.

© Copyright 2017 Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. All rights reserved. Any unauthorized copying or reproduction is strictly prohibited.

References

[1] Hardas Makhijaa was the Mayor of Ulhasnagar from 3 May 1999 to 5 April 2002. Interviewed on 19 August 2017, in Ulhasnagar.

[2] Agarwal, Saaz, ‘The Sindhworkis Unique Global Diaspora’, Sahapedia, 2016, < https://www.sahapedia.org/the-sindhworkis-unique-global-diaspora> (Accessed on 24 August 2016)

[3]Bhavnani, Nandita., ‘The Making of Exile: Sindhi Hindus and the Partition of India’ (New Delhi, Tranquebar Press, 2014).

[4] The Sindhis are classified not according to caste but by profession. The Amils, or Sindhi Hindus who belong to the educated segment of the pervasive Lohana caste (although there are tribals and other groupings too), are largely from Hyderabad, Sindh. Hyderabad, Sindh, was the former capital of Sindh and the educational and cultural hub of the Province. It was the British who shifted the capital city from Hyderabad (Sindh) to Karachi. The Amils were treasurers and book-keepers to the Balochi Talpur rulers of Sindh. When Sindh came under the English East India Company Rule in 1843, they took up key posts as administrators in the colonial government.

[5] The Bhaibands (Sindhworkis), also travelled to Africa, Europe (going as far north as Scandanavia), the United States of America, South America, Central America,, Australia, and South-East Asia.

[6] Manufacturing units in Ulhasnagar are largely in the informal sector and data on sales and volumes for these units are difficult to come by. Most manufacturing is located in Sector 5 of this township.

[7] There are five Navjivan Societies within Greater Mumbai, all set-up by a Congress politician from Sindh, Jethiben Sipahimalani, who became the first vice chairperson of the Bombay Legislative Council (Vidhan Sabha). The first Navjivan Society at Mahim was intended for Sindhi refugees, and was completed in 1959. Bhavnani, p. 204-05.

[8] Ibid, p. 205. These were set up by Bhagwansing Advani.